Today, we will discuss Oligopoly, a market structure quite different from the previously studied ones. Oligopolies are prevalent in many industries worldwide, including in our South Asian region. Understanding this concept will help us analyze various markets, including telecommunications, automobile industries, and global tech giants.

Introduction

An Oligopoly is a market structure where a few large firms dominate the market. These firms hold significant market power, allowing them to influence prices and output levels. Unlike perfect competition, where many small firms exist, or a monopoly with only one firm, an oligopoly has only a handful of players.

Price Setting:

Interdependence: Oligopoly firms consider the pricing strategies of competitors before setting their prices.

Collusion: Firms may agree, formally or tacitly, to set higher prices to avoid price wars.

Price Leadership: The dominant player sets the price, and others follow.

Kinked Demand Curve: Firms may keep prices stable because lowering them triggers a price war while increasing costs to customers’ losses.

In oligopolies, firms balance costs, revenues, and strategic interactions to maintain stable profits.

How Oligopolies Survive/Prevail

Oligopolies are market structures where a few firms dominate an industry. Unlike perfect competition, where many small firms compete, or monopoly, where one firm controls the market, oligopolies involve a few large firms. These firms are interdependent; meaning the actions of one firm can significantly affect the others. Oligopolies prevail due to several key factors:

1. High Barriers to Entry

Economies of Scale: Large firms benefit from economies of scale, which means they can produce goods at a lower cost than smaller firms. This cost advantage discourages new entrants.

Capital Requirements: Many industries where oligopolies exist require significant upfront investment in infrastructure, technology, or research and development. For example, the automotive industry is dominated by a few large companies like Toyota, Volkswagen, and General Motors because the cost of entering the market is unaffordable.

Regulatory Barriers: Governments may impose regulations that make it difficult for new firms to enter the market. These regulations could include licensing requirements, safety standards, or environmental regulations that are costly to comply with.

2. Brand Loyalty and Consumer Behavior

Brand Recognition: Oligopolistic firms often invest heavily in advertising and brand-building. As a result, consumers become loyal to certain brands, making it difficult for new entrants to attract customers. For example, in the soft drink industry, Coca-Cola and Pepsi have such strong brand identities that new competitors struggle to gain market share.

Customer Inertia: Even if a new firm offers a better or cheaper product, consumers may stick with the brands they know due to their routine or perceived risk in switching.

3. Non-Price Competition

Innovation and Product Differentiation: Oligopolistic firms often compete through innovation and product differentiation rather than price cuts. This can involve introducing new features, improving product quality, or offering better customer service. For instance, in the smartphone industry, companies like Apple and Samsung regularly release new models with advanced features to maintain their market positions.

Advertising: Heavy advertising budgets allow oligopolistic firms to maintain a strong market presence and differentiate their products from those of competitors. This makes it difficult for new firms to compete without similarly large advertising investments.

4. Strategic Behavior and Collusion

Tacit Collusion: Firms in an oligopoly might not explicitly agree to fix prices, but they can engage in tacit collusion, where they follow each other’s pricing strategies. This behavior helps maintain high prices and profits in the market.

Price Leadership: One firm in the oligopoly might become the price leader, setting prices that the others follow. This can prevent price wars and stabilize the market.

Game Theory and Strategic Decision-Making: Oligopolistic firms often use game theory to anticipate and respond to the actions of their competitors. This strategic behavior helps them maintain their market positions. The “prisoner’s dilemma” is a common example used to illustrate how firms might choose to cooperate rather than compete aggressively.

World Around Us: How Oligopoly Prevails

Case Study 1: The Airline Industry

- High Barriers to Entry: The airline industry is capital-intensive, requiring massive investments in aircraft, infrastructure, and regulatory compliance. This has led to an oligopolistic market dominated by a few major airlines, such as Delta, United, and American Airlines in the United States. New entrants find it challenging to compete due to the high costs and established customer loyalty.

- Non-Price Competition: Airlines often compete on services like frequent flyer programs, in-flight entertainment, and customer service rather than price alone. This differentiation helps maintain their market positions.

Case Study 2: The Oil Industry

- Strategic Behavior: The global oil market is dominated by a few major companies, such as ExxonMobil, BP, and Shell, as well as state-owned entities like Saudi ARAMCO. These firms often engage in strategic behavior, including controlling production levels to influence global oil prices. OPEC, a cartel of oil-producing countries, is an example of how oligopolistic firms can collaborate to maintain market power and control prices.

- High Barriers to Entry: The oil industry requires significant investment in exploration, drilling, and refining, making it difficult for new firms to enter the market. Regulatory barriers, such as environmental laws, also add to the entry costs.

- Automotive Industry: As of 2023, Toyota, Volkswagen, and General Motors collectively control a significant share of the global automotive market. These companies benefit from economies of scale, allowing them to produce vehicles at a lower cost per unit than potential new entrants.

- Soft Drink Industry: Coca-Cola and Pepsi control around 60% of the global soft drink market. Their dominance is maintained through extensive advertising and brand loyalty. A study from Statista shows that Coca-Cola’s brand value was approximately $83.8 billion in 2022, making it one of the most valuable brands globally.

- Oil Industry: According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), OPEC’s influence on global oil prices remains strong, with the cartel controlling about 40% of the world’s oil production. OPEC’s decisions on oil production levels can significantly impact global oil prices.

Collusion vs. Competition in Oligopolies

Oligopolies, where a few firms dominate the market, can either choose to cooperate (collude) or compete. Each path has different implications for the market, consumers, and the firms involved.

Collusion

Collusion occurs when firms in an oligopoly agree, formally or informally, to reduce competition among them. This can include setting prices, controlling output, or dividing the market geographically. The goal is to maximize joint profits by acting as a single entity, like a monopoly.

How It Happens:

- Formal Collusion (Cartels): Firms openly agree on prices, production levels, or market shares. Cartels are illegal in many countries because they lead to higher prices and reduced competition. However, some still operate, particularly in international markets.

- Tacit Collusion: Firms may not openly agree but still follow each other’s pricing and production decisions, understanding that mutual cooperation benefits them all. This is an unspoken mutual understanding phenomenon.

World Around Us: Collusion

Case Study: OPEC Cartel

- The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is a classic example of a cartel. Founded in 1960, OPEC includes major oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Iran. They collectively decide on oil production levels to influence global oil prices.

- Impact: By controlling supply, OPEC has been able to manipulate oil prices, sometimes causing significant economic effects worldwide. For instance, in the 1970s, OPEC’s decision to cut oil production led to the oil crisis, which caused a severe global economic slowdown.

- Figures: OPEC countries hold about 79.4% of the world’s proven oil reserves. In 2021, OPEC’s market share in global oil production was around 35%.

- Legal Risks: In many countries, collusion is illegal. Companies found guilty of collusion can face hefty fines, legal costs, and damaged reputations.

- Instability: Even within cartels, individual firms have an incentive to cheat by secretly lowering prices or increasing output to gain more market share. This makes collusion hard to maintain.

Competition

In contrast to collusion, firms in an oligopoly may choose to compete. This competition can occur in several forms, such as price competition, advertising, or product innovation. Competition can benefit consumers by leading to lower prices, better quality products, and more choices.

Forms of Competition:

- Price Wars: Firms may engage in price cuts to gain market share. However, this can erode profits for all players.

- Non-Price Competition: Firms might compete through advertising, product features, or customer service rather than lowering prices. This is common in markets where price competition is less effective.

World Around Us: Competition

Case Study 1: Hyundai vs. Kia in South Korea

- Hyundai and Kia are both part of the Hyundai Motor Group. Despite their affiliation, they compete aggressively in the South Korean market and globally.

- Competition: Hyundai and Kia often introduce competing models in similar segments, each with distinct features and pricing strategies. For instance, in the compact car segment, Hyundai’s i30 competes directly with Kia’s Ceed, with both brands emphasizing different aspects like design, technology, and price.

- Impact: This competition drives innovation and variety in the market, providing consumers with more options and better products. Despite being part of the same group, their competition helps maintain the overall group’s dominance in the automotive market.

- Market Share: Hyundai and Kia together held approximately 80% of the South Korean market in 2021. However, their rivalry ensures that they continuously push for better products and services to retain their customer base.

- Global Reach: Both brands have expanded significantly worldwide, with Hyundai ranking as the third-largest automaker globally by sales in 2021, with over 6.6 million units sold.

Case Study 2: Oligopoly in the European Aviation Industry

- One real-world example of oligopoly behavior is the European aviation market, especially the competition among Ryanair, EasyJet, and traditional carriers like Lufthansa.

- Collusion Potential: European airlines have faced accusations of colluding to limit competition by controlling routes and pricing structures. However, regulatory bodies like the European Commission closely monitor such behavior to prevent unfair practices.

- Competition and Innovation: Despite this, competition remains strong. Airlines invest heavily in innovation, from fuel-efficient aircraft to customer service improvements, to differentiate themselves.

- Pricing Behavior: The kinked demand curve applies as airlines may keep prices stable to avoid triggering a price war, yet occasionally engage in aggressive pricing to capture market share.

- Facts and Figures: In 2019, Ryanair carried over 150 million passengers, while EasyJet carried over 96 million. Their strategies are influenced by balancing competitive pricing and maintaining profitability in a tightly contested market.

Summary

The decision between collusion and competition in oligopolies has significant implications. Collusion can lead to higher prices and reduced consumer choice but is risky and often unstable. On the other hand, competition, while potentially eroding profits, drives innovation, improves product quality, and benefits consumers. Understanding the dynamics between these two approaches is crucial for analyzing oligopolistic markets.

Kinked Demand Curve

The kinked demand curve model suggests that in an oligopolistic market, the demand curve facing each firm has a distinct “kink.” This kink occurs because firms believe that if they reduce their prices; competitors will follow, leading to inelastic demand. However, if they increase their prices, competitors will not follow, leading to elastic demand.

1. Shape of the Kinked Demand Curve

Two Segments:

- Above the Kink: The demand curve is more elastic. If a firm raises its prices, consumers can easily switch to competitors, causing a significant drop in sales.

- Below the Kink: The demand curve is less elastic. If a firm lowers its prices, competitors are likely to match the price decrease, so the firm does not gain much in terms of sales volume.

2. Price Rigidity

The kinked demand curve explains why prices in oligopolistic markets tend to be sticky. Firms are reluctant to change prices because raising prices could lead to a significant loss of market share, and lowering prices might not increase market share but will reduce profits.

3. Marginal Revenue Curve

The marginal revenue curve associated with the kinked demand curve is discontinuous at the kink. This gap means that even if marginal costs fluctuate, prices may remain stable.

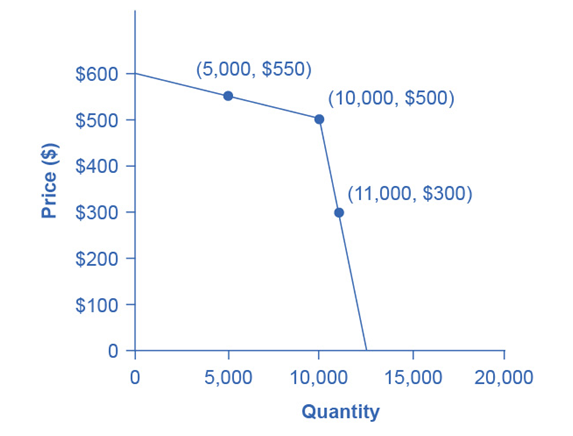

Graphical Representation of Kinked Demand Curve

- The graph shows a demand curve that has a “kink” or a sharp bend at a specific point.

- The demand curve is steeper below the kink and flatter above the kink.

Price and Quantity Points:

- (5,000, $550): At this point, the firm is selling 5,000 units at a price of $550.

- (10,000, $500): The kink occurs at 10,000 units and a price of $500.

- (11,000, $300): If the firm lowers the price to $300, the quantity sold increases to 11,000 units.

Price Rigidity:

The kinked demand curve theory suggests that prices in an oligopoly are relatively stable because of the firm’s strategic interdependence.

Above the Kink: If a firm increases prices above the current level, competitors will not follow, leading to a significant loss of market share and customers. This is why the demand curve is flatter above the kink.

Below the Kink: If a firm lowers prices, competitors are likely to follow suit, leading to a smaller gain in market share. This is why the demand curve is steeper below the kink.

Revenue Curve in the Kinked Model

Figure 13.1 illustrates a kinked demand curve, common in oligopoly markets. The two different slopes indicate that the firm’s demand is more elastic for price increases and less elastic for price decreases.

- In the kinked demand curve model, the revenue curve typically follows the demand curve but has a “kink” at the point where the elasticity changes.

- The firm maximizes revenue at the quantity corresponding to the kink (10,000 units at $500). This is because above this price, any increase would sharply reduce the quantity demanded, and below it, any decrease would reduce revenue due to the lower price.

Oligopoly Firms’ Profits, Losses, and Market Dynamics

Profit Maximization:

- Firms in oligopoly can maximize profits by setting prices at the kink (e.g., $500), where revenue is relatively stable even if marginal costs fluctuate.

- Profits depend on the firm controlling costs and differentiating its product.

Losses:

- Losses occur when costs increase beyond the price firms can charge (e.g., rising factor costs or failure to keep prices competitive).

- If firms lower prices to $300, revenue and profits would decrease unless they increase production to offset it, but there are limits to how much they can expand.

Entry of New Firms:

- New firms can enter the market when there is excess profit. However, high barriers (like capital, technology, or brand loyalty) in oligopolies often limit this.

- Example: The entry of new airlines in previously monopolistic markets has increased competition and reduced prices.

Exit of Firms:

- Firms may exit when they can no longer cover their average costs, either due to intense competition, rising costs, or regulatory changes.

- Example: In the telecom industry, smaller players often leave when unable to sustain competition with giants.

No Loss-No Profit Situations:

- Firms in an oligopoly may reach a breakeven point where they cover all their costs but make no profit.

- This could occur due to intense competition or changing demand. Firms may also operate in this range temporarily as a strategy to maintain market share.

Rising Prices of Factors of Production:

- Higher input costs (e.g., labor or raw materials) shift the marginal cost curve upwards.

- Firms might respond by raising prices if demand allows, but this could lead to a decrease in the quantity sold due to the elastic part of the demand curve.

- Example: In the steel industry, rising ore prices force firms to adjust production and pricing strategies.

Rising Budget for Advertising:

- Firms in an oligopoly often increase their advertising spending to differentiate products.

- This can increase the firm’s demand curve, allowing them to maintain higher prices without losing market share.

- Example: Pepsi and Coca-Cola’s heavy advertising keeps their demand relatively inelastic despite price competition.

Implementation of Taxes:

- Taxes increase firms’ production costs. Firms may pass these on to consumers by increasing prices.

- In a kinked demand curve scenario, raising prices could result in a sharp reduction in the quantity sold.

- Example: New environmental taxes on oil production have led to adjustments in pricing strategies for firms like ExxonMobil and BP.

Implementation of Subsidies:

- Subsidies reduce production costs, allowing firms to lower prices or increase profitability without changing prices.

- In oligopolies, firms might choose not to lower prices but instead use the extra margin to invest in other areas like innovation or expanding capacity.

- Example: Government subsidies to electric vehicle producers have allowed firms like Tesla to lower prices and increase market penetration.

Market Efficiency in Oligopolies

Market efficiency occurs when resources are allocated in a way that maximizes total economic welfare, ensuring that goods and services are produced at the lowest possible cost and sold at a price reflecting their true value. However, in oligopolies, market efficiency is often compromised due to limited competition and strategic behavior by firms.

Example: Market Inefficiency of Airlines Industry

In the airline industry, which often operates as an oligopoly in many regions, a few major firms dominate the market. These firms set prices above marginal costs to maximize profits, leading to allocative inefficiency. Allocative inefficiency occurs when the price of a good exceeds its marginal cost, meaning fewer consumers can afford the good or service at a higher price.

Oligopolistic Dynamics and Efficiency:

Profit Maximization:

In an oligopoly, firms maximize profits by setting prices at a point where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. However, these prices are often higher than in perfectly competitive markets, leading to reduced output and higher prices for consumers. For example, an airline might set ticket prices at $500, even though the marginal cost of providing an additional seat is only $300.

Allocative Inefficiency:

Because oligopoly firms have market power, they can set prices above marginal cost. This results in fewer consumers being able to purchase the product, reducing overall welfare in the market. The airline industry exemplifies this, as airlines often restrict seats to keep prices high, limiting the number of consumers who can travel.

Productive Inefficiency:

Oligopolies may also experience productive inefficiency, where goods are not produced at the lowest possible cost. This can happen when firms are not driven by competition to reduce costs and innovate. In the airline industry, carriers might not operate at full capacity or invest in the most efficient technology due to the least competitive pressure.

Improvements in Efficiency: Entry of New Firms

An example of improving efficiency occurred when new low-cost airlines like AirBlue and SereneAir entered the Pakistani market. These new entrants increased competition, leading to lower prices and better service for consumers. More efficient pricing and resource allocation resulted from this competition, improving overall market efficiency.

Summary

While oligopolies can suppress market efficiency by setting higher prices; and restricting output, introducing competition through new entrants or regulation can push the market toward more efficient outcomes.

World Around Us: Kinked Demand

Case Study 1: Oligopoly Exit and Entry – The Smartphone Industry

The smartphone industry is a classic oligopoly. A few key firms control the majority of the market. Examples include Apple, Samsung, and Huawei. Each company watches the others closely and competes on features like technology, branding, and price. When one firm leaves the market, another often fills the gap.

LG Exits the Smartphone Market and Xiaomi Expands

LG’s Exit (2021)

- Reason for Exit: LG Electronics announced its exit from the smartphone market in April 2021. LG had been struggling for years with losses in its smartphone division, facing stiff competition from dominant players like Apple, Samsung, and Chinese brands.

- Market Share: LG held about 2% of the global market before its exit. Its struggles were mainly due to failure to innovate and low brand recognition in key markets like the U.S. and Europe.

- Impact: LG’s exit created a gap, particularly in mid-range and low-cost smartphones. LG has been a strong player in South Korea and the U.S., especially in budget-friendly models.

Xiaomi’s Entry and Expansion

Xiaomi’s Growth: At the same time LG exited, Xiaomi began to aggressively expand its presence. Xiaomi, a Chinese brand, had already been successful in emerging markets like India but started pushing into global markets such as Europe and the U.S.

Market Share: By the end of 2021, Xiaomi surpassed Apple and Samsung at various times to become the world’s largest smartphone vendor. It captured around 17% of the global market.

Strategy: Xiaomi filled the gap left by LG, particularly in offering high-quality phones at affordable prices. It targeted both low-cost segments and premium segments.

Important Facts and Figures

- LG’s Market Share (2020): 2% globally, with 9% in the U.S. market before exit.

- Xiaomi’s Global Market Share (2021): 17%, surpassing Apple and Samsung at different points during the year.

- LG’s Financial Losses (2015-2020): LG’s smartphone division lost nearly $4.5 billion over six years.

- Xiaomi’s Revenue (2021): $51 billion, with a significant rise in international sales after LG’s exit.

Real-World Impact

- South Korea: Samsung benefitted the most from LG’s exit in its home market, strengthening its already dominant position.

- India: Xiaomi further strengthened its position as the market leader in India, capturing over 25% of the market by 2022.

- U.S. Market: After LG’s exit, brands like Motorola and OnePlus, alongside Xiaomi, moved to capture market share in the budget segment.

Summary

The exit of LG and the entry/expansion of Xiaomi show how oligopoly firms react to market shifts. When one company leaves, some other finds an opportunity to enter the market. Hence it increases competition among the remaining firms.

References

- LG Official Announcement of Exit

- Market Analysis: Canalys Reports on Xiaomi’s Market Share

- Financial Data on LG’s Exit and Xiaomi’s Growth: Statista

This case is a good example of oligopolistic competition in the global market. When a firm exits, another firm takes its place, intensifying the competition.

Case Study 2: The Oil Industry (OPEC)

OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) is a classic example where the kinked demand curve can be applied. OPEC’s member countries produce a significant portion of the world’s oil, and their pricing strategies have a major impact on global oil prices.

Kinked Demand in Action

- Price Decreases: If one member of OPEC reduces its oil price, other members are likely to do the same to maintain market share, leading to minimal gains in sales volume but significant revenue loss.

- Price Increases: Conversely, if one member increases its price, other members might not follow, leading to a loss of market share for the firm that increased prices.

- Fact: In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, OPEC faced challenges with oil prices dropping sharply. Despite some members wanting to lower production to increase prices, they were hesitant due to the fear that other members might not follow, which reflects the kinked demand curve scenario.

Case Study 3: Telecommunications Industry

- In the telecommunications industry, especially in countries like India and Pakistan, the market dynamics often reflect the characteristics of a kinked demand curve. Companies like Airtel, Jio, and PTCL face situations where they tend to avoid engaging in price wars due to the potential negative impact on profitability.

- Fact: A study in India showed that when one telecom company reduced its data prices by 20%, competitors followed, but the overall market revenue dropped by 5% due to reduced margins.

Game Theory in Oligopoly

Game theory is a branch of mathematics used to study strategic interactions among rational decision-makers. In economics, it helps us understand how firms in an oligopoly make decisions considering the actions of their competitors. Firms in an oligopoly are interdependent, meaning the actions of one firm impact the decisions of others. Game theory allows firms to analyze potential outcomes based on their rivals’ responses.

Key Concepts:

- Nash Equilibrium: A key concept in game theory is the Nash Equilibrium, where no player can benefit by unilaterally changing their strategy. In an oligopoly, this could occur when firms choose pricing strategies that maximize profits given the actions of their competitors.

- Prisoner’s Dilemma: A scenario where two firms may choose to compete (defect) or collude (cooperate). The dilemma arises because, while cooperation might yield the best overall outcome, the fear of the other firm cheating leads them to compete.

- Dominant Player in Game Theory: In game theory, a dominant player (or dominant firm) refers to a firm or entity that holds a significant advantage over its competitors due to its size, resources, market power, or influence. This firm can often set or influence strategies that other players in the market must follow.

Role of Dominant Player in Setting the Final Strategy

- Influencing the Market: The dominant player typically has a larger market share, greater control over pricing, and the ability to shape market outcomes. Its strategies heavily influence the decisions of other players in the game.

- Price Leadership: In oligopolies, the dominant player may act as a price leader. Other firms in the market often follow the dominant player’s pricing decisions to avoid price wars.

- Strategic Decisions: The dominant player’s decisions regarding production levels, investment, or pricing can force smaller players to adapt their strategies accordingly. Smaller firms might either align with the dominant firm’s strategy or try to differentiate themselves to survive.

- Stability or Disruption: The dominant player’s strategy can either stabilize the market by setting clear expectations (e.g., through tacit collusion or price leadership) or disrupt it if the firm pursues aggressive tactics like predatory pricing.

- In essence, the dominant player’s role in game theory is crucial in setting the tone and direction of the final strategies that emerge in a competitive environment. Smaller players often react to or align with the moves of the dominant player.

Nash Equilibrium

Nash Equilibrium is a concept in game theory where no player can improve their outcome by changing their strategy, given that all other players keep their strategies unchanged. At this point, every player’s strategy is optimal in response to the others, leading to a stable outcome.

Case Study 1: Sugar Industry in Pakistan (2018-2022)

The sugar industry in Pakistan has been dominated by a few large players, much like the cement industry. These include politically influential families and groups that control a significant portion of the market. In recent years, the industry has faced scrutiny for cartel-like behavior, where firms appeared to engage in price manipulation and supply control to maximize profits. This behavior can be analyzed through the lens of Nash Equilibrium in game theory.

Payoff Matrix Example:

Let’s consider two dominant sugar firms in Pakistan—Firm A and Firm B—which control a large share of the market. Each firm has the choice to either set high prices or low prices for sugar. The following payoff matrix reflects their possible profits (in billions of rupees) based on their pricing strategies:

| Strategies/Payoffs | Firm B: High Price | Firm B: Low Price |

| Firm A: High Price | (12, 12) | (4, 16) |

| Firm A: Low Price | (16, 4) | (6, 6) |

- (12, 12): Both firms set a high price and enjoy stable, substantial profits.

- (4, 16) or (16, 4): One firm lowers its price while the other maintains a high price, leading to a larger market share for the firm with the lower price.

- (6, 6): Both firms set a low price, leading to moderate profits for both.

Nash Equilibrium:

- The Nash Equilibrium in this scenario occurs when both firms choose to set high prices (resulting in (12, 12).

- This is because, if either firm deviates and chooses to lower its price, it risks triggering a price war that would ultimately lead to reduced profits for both firms. For example, if Firm A decides to lower its price while Firm B maintains high prices, Firm A might initially gain market share but would then force Firm B to lower its prices, leading to the (6, 6) outcome, which is less profitable for both.

- This illustrates how, even in the absence of explicit collusion, firms in oligopolistic markets may adopt pricing strategies that resemble collusion due to mutual understanding and market dynamics.

Important Facts and Figures

- High Prices Despite Surplus: During 2018-2020, despite ample sugar production, prices in the domestic market rose significantly. This was primarily due to the control exerted by a few large firms that restricted supply to maintain high prices. According to a Sugar Inquiry Commission Report in 2020, these firms appeared to have coordinated their pricing and supply strategies to maximize profits.

- Nash Equilibrium Realized: Firms realized that aggressive price-cutting would reduce profits across the industry, so they collectively maintained high prices. Although this may not have involved explicit collusion, it can be explained by the Nash Equilibrium where all firms found it in their best interest to keep prices high rather than risk a price war.

- Example (2020-2021): In 2020, sugar prices surged by 30-40% despite steady production levels. The Pakistan Competition Commission investigated the industry for cartelization, but the pricing behavior can be understood through game theory. Firms avoided price cuts, as lowering prices would have led to a less profitable outcome for all players involved.

- Profit Margins: The firms enjoyed record profits during this period due to sustained high prices, while consumers suffered due to inflated costs for an essential commodity.

Impact on Development in Pakistan:

- Increased Cost of Living: The artificially high sugar prices led to higher food prices, which disproportionately affected low-income households. Sugar is a staple in the Pakistani diet, and price manipulation directly impacts the purchasing power of the general public.

- Political Economy: The dominance of politically connected firms in the sugar industry allowed them to maintain their pricing power and influence policy decisions. This not only distorted the market but also slowed economic development by diverting resources from more productive sectors.

Summary

The sugar industry in Pakistan during 2018-2022 exemplifies the use of Nash Equilibrium in an oligopoly. The firms involved found it more profitable to maintain high prices than engage in price competition, leading to abnormally high profits for the industry but detrimental effects on the general public. Encouraging competition and enforcing fair pricing policies are crucial steps to ensuring that such industries benefit the broader economy.

References:

- Sugar Inquiry Commission Report, 2020.

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Sugar Price Index (2018-2022).

- Competition Commission of Pakistan, 2020 Price Fixing Investigation Report.

- Economic Survey of Pakistan 2021-22, Chapter on Agriculture and Industry.

Case Study 2: Game Theory in Pakistan’s Banking Sector

Let’s consider a simplified example involving two firms, Firm A and Firm B, in Pakistan. Both firms have two strategies: they can either “Advertise or Not Advertise”. The payoffs represent their profits in millions of rupees.

| Firm B / Firm A | Advertise | Not Advertise |

| Advertise | 4, 4 | 10, 2 |

| Not Advertise | 2, 10 | 6, 6 |

- If both firms choose to advertise: Both earn 4 million rupees.

- If Firm A advertises and Firm B does not: Firm A earns 10 million, and Firm B earns 2 million.

- If Firm B advertises and Firm A does not: Firm B earns 10 million, and Firm A earns 2 million.

- If neither firm advertises: Both firms earn 6 million.

- Nash Equilibrium: The Nash equilibrium occurs when neither firm has an incentive to change its strategy given the other firm’s choice. In this case, the equilibrium is when both firms choose to Advertise and earn 4 million rupees each. This is because if any firm independently decides to not advertise, they will lose profit.

- Banking Sector of Pakistan: In Pakistan, during the 2000s, major banks like HBL (Habib Bank Limited), UBL (United Bank Limited), and MCB (Muslim Commercial Bank) found themselves in a strategic dilemma regarding interest rates on savings accounts. This was an example of game theory at play, particularly the Nash equilibrium.

- Banks in Pakistan needed to balance attracting depositors by offering higher interest rates while maintaining profitability. If one bank decided to cut its rates while others maintained them, it risked losing depositors but could potentially maintain its margins by reducing payouts. Conversely, if they all kept rates high, they would secure depositors but experience a reduction in profits due to higher interest expenses.

- Initial Decisions: Banks initially competed by raising interest rates to attract more customers. However, this led to decreasing profit margins across the industry due to increased payout obligations.

- Nash Equilibrium Realized: Eventually, many banks settled on slightly lower, but more stable, interest rates that balanced attracting depositors and maintaining profitability. This was a classic Nash equilibrium, as no single bank had an incentive to unilaterally deviate from the prevailing rate structure, fearing negative outcomes (such as losing customers or reducing profits).

- Interest Rate Trends: Since 2000-2005, the average interest rate on savings accounts in Pakistan fluctuated between 3-5%. Banks initially spiked rates up to 6% but later adjusted downwards to around 4% after realizing diminishing returns on higher payouts.

Reference: “Banking Sector Reforms in Pakistan” by the State Bank of Pakistan, State Bank Report

The Prisoner’s Dilemma in Oligopoly

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a fundamental concept from game theory, and it provides deep insights into the behavior of firms in an oligopoly. This section will explain the concept, and how it applies to oligopolistic markets, and offers a real-world case study to illustrate these ideas.

Basic Concept:

- The Prisoner’s Dilemma involves two players (firms in this case) who must decide whether to cooperate (collude) or compete without knowing the other player’s decision.

- If both firms choose to cooperate (collude), they can maximize their joint profits. However, each firm has an incentive to cheat (compete), as cheating while the other firm cooperates yields the highest individual profit.

- The dilemma arises because if both firms choose to cheat (compete), they both end up worse off than if they had colluded. This fear of being outcompeted often leads firms to compete, even though collusion would be more profitable.

Application in Oligopoly:

- In an oligopoly, firms face similar choices. They can either agree to set higher prices (collude) or undercut each other by lowering prices (compete).

- While collusion can maximize joint profits, the temptation to cheat (by offering lower prices to attract more customers) is strong. However, if both firms cheat, a price war may ensue, leading to reduced profits for all.

World Around Us: Prisoner’s Dilemma – European Airlines

- The European airline industry is a prime example of how the Prisoner’s Dilemma operates in real-world oligopolies.

- Major airlines like Lufthansa, British Airways, and Air France-KLM operate in a market where they could benefit from keeping ticket prices high.

The Dilemma:

- Collusion: If all airlines keep prices high, they all benefit from higher profit margins. This would be similar to both firms in the Prisoner’s Dilemma deciding to remain silent (collude).

- Cheating: However, if one airline decides to lower its prices, it could attract more customers from competitors. This is akin to one prisoner betraying the other.

- Outcome: If all airlines fear losing customers and start lowering prices, a price war develops. This leads to lower prices across the board, and all airlines earn less profit than they would have if they had colluded.

- Price Wars: In the early 2000s, European airlines experienced significant price wars, especially with the rise of low-cost carriers like Ryanair and EasyJet. Established airlines were forced to lower their prices to compete, leading to reduced profit margins across the industry.

- Important Fact: In 2019, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) reported that European airlines had a net profit margin of just 4.2%, compared to 9.1% in North America. This difference highlights the impact of intense competition in Europe.

- Collusion Attempts: While explicit collusion is illegal under European Union competition law, airlines have occasionally been accused of tacit collusion, such as when multiple airlines simultaneously introduce similar fees or surcharges without direct communication.

- Conclusion: The European airline industry illustrates the difficulty of maintaining high prices in an oligopoly. The fear of being destabilized by competitors often leads to aggressive competition, reducing profits for all involved.

Dominant Players in Oligopoly

Dominant players are the leading firms in a market with the most power, influencing prices, supply, and market trends due to their large size or control over resources.

Case Study: Cement Industry in Pakistan

The cement industry in Pakistan is a prime example of an oligopolistic market where a few dominant players control the majority of production and pricing. The cement market is highly concentrated, with the top five firms controlling over 70% of the market. Major companies like Lucky Cement, DG Khan Cement, and Bestway Cement dominate the industry. These firms have used their market power to set prices and, at times, earn abnormally high profits.

Facts & Figures:

Market Concentration: The top 5 cement manufacturers control over 70% of the market share

Price Manipulation Allegations: In 2020, the Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) investigated and fined multiple cement companies for allegedly forming a cartel and manipulating prices. Prices increased by 40% between 2019 and 2020.

Profit Margins: Cement companies reported record-high profits during this period, despite stable production costs and low demand.

How Dominant Players Set High Prices:

Cartelization: Major players in the industry have been accused of colluding to control supply and artificially raise prices. By reducing production or keeping it fixed while demand increases, these companies could push prices higher.

Nash Equilibrium Realized: The firms eventually realized that aggressive price-cutting led to reduced profits for all players. Hence, they reached a tacit agreement (Nash Equilibrium) where all firms maintained high prices, ensuring stable profits.

Price Leadership: Lucky Cement, the largest player, often sets prices that others in the industry follow, maintaining higher-than-competitive pricing.

Barriers to Entry: High startup costs and regulation requirements limit new entrants, allowing existing players to maintain their dominance and set prices without the threat of significant competition.

Unstated Collusion: According to a report by the All Pakistan Cement Manufacturers Association (APCMA), during 2018-2020, the cement industry experienced a period of high prices despite demand fluctuations. Prices remained relatively stable, which was seen as a result of this unstated collusion.

Scrutiny: In 2021, the industry faced scrutiny from Pakistan’s Competition Commission for potentially engaging in price-fixing, reflecting the delicate balance firms must maintain in an oligopoly.

Impact on the General Public:

Higher Construction Costs: The artificially high cement prices increased the cost of construction, impacting infrastructure development and housing projects across Pakistan. Public sector projects, such as Naya Pakistan Housing, faced delays and higher costs due to inflated cement prices.

Inflation Pressure: The higher cost of cement contributed to overall inflation in the economy, putting more pressure on already struggling consumers.

Suggestions: Role of Dominant Players to Benefit the Public

Promote Fair Pricing: Dominant players should adopt ethical pricing strategies that reflect actual production costs rather than exploit their market power. The government can encourage this through more robust antitrust laws and monitoring.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Companies should invest in public welfare projects, such as affordable housing and infrastructure that align with national development goals. This not only benefits society but also helps firms improve their public image.

Increase Production Efficiency: Firms should focus on increasing production efficiency rather than collusion. Efficient firms can offer lower prices, benefiting the general public while maintaining profitability.

Support Small Businesses: Dominant firms could support smaller competitors by providing technical assistance or investing in industry-wide innovations. This would reduce concentration and promote competition, ultimately lowering prices for consumers.

Fostering Innovation: The industry could invest in new technologies to lower production costs and pass these savings on to consumers, spurring development in underdeveloped regions.

How Dominant Players Distort Development:

Monopoly Profits: By setting artificially high prices, dominant players in Pakistan slow down infrastructure and housing development, which are critical for an underdeveloped country like Pakistan. This reduces economic growth and increases income inequality.

Resource Allocation: High cement prices force the government and private sector to allocate more resources to construction, diverting funds from other essential sectors like education and healthcare.

In summary, while dominant players can distort economic development by setting high prices and earning abnormally high profits, they can also play a positive role by engaging in fair competition, lowering prices, and investing in national development projects.

References

- Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP), Annual Report 2021.

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Cement Price Index 2020-2022.

- News article from “Dawn” detailing the 2020 cement cartel investigation.

- Pakistan Economic Survey 2021-2022, Chapter on Industry and Manufacturing.

Tradeoffs of Imperfect Competition in Oligopolies

Imperfect competition, particularly in oligopolies, introduces several tradeoffs for consumers, firms, and the overall market. Unlike perfect competition, where many firms sell homogeneous products, oligopolies are characterized by a few large firms dominating the market. This leads to both positive and negative consequences that shape how consumers, businesses, and economies interact.

Key Tradeoffs in Oligopolies

Pricing Power and Consumer Impact

- Tradeoff: Oligopoly firms have significant pricing power, allowing them to set prices higher than in perfectly competitive markets.

- Positive Outcome: This can lead to stable prices over time. Consumers often benefit from improved quality, innovations, and differentiated products.

- Negative Outcome: Higher prices can reduce consumer surplus, meaning that consumers pay more than in a perfectly competitive market where prices are driven down by competition.

- Example: The airline industry is an oligopoly in many countries, where a few major airlines dominate. While this allows for better flight services and newer planes, ticket prices are generally higher than they would be in a more competitive market.

Innovation vs. Efficiency

- Tradeoff: Oligopoly firms tend to invest heavily in research and development (R&D) to differentiate their products, leading to innovation.

- Positive Outcome: Consumers benefit from innovation in products and services. For example, in the smartphone industry, companies like Apple and Samsung invest significantly in R&D, leading to new technologies, such as advanced cameras, 5G capabilities, and software features.

- Negative Outcome: Oligopolies may not always operate at maximum efficiency. Firms might spend too much on advertising and branding, creating unnecessary costs that could be passed on to consumers.

- Example: In the pharmaceutical industry, companies often develop groundbreaking drugs due to their ability to fund R&D, but the costs of these drugs are often extremely high due to the lack of competition.

Barriers to Entry and Market Control

- Tradeoff: Oligopolies often have high barriers to entry, which prevent new firms from entering the market and competing.

- Positive Outcome: This leads to stability for the existing firms, allowing them to invest in long-term projects, employ more people, and ensure consistent supply.

- Negative Outcome: Consumers may suffer from a lack of variety and choice due to the lack of competition. Moreover, these barriers protect inefficient firms, allowing them to survive despite poor performance.

- Example: The telecom industry in many countries is dominated by a few firms. In India, companies like Jio, Airtel, and Vodafone control the majority of the market, making it difficult for new entrants to offer competitive pricing and services.

Collusion and Anti-Competitive Practices

- Tradeoff: Oligopolies may engage in collusion, either formally (cartels) or informally, to set prices or output levels, reducing the benefits of competition.

- Positive Outcome: While illegal, collusion can lead to price stability in the short term, avoiding destructive price wars that could harm firms and employees.

- Negative Outcome: Collusion reduces consumer welfare by keeping prices artificially high, leading to reduced output and a loss of efficiency in the market.

- Example: The OPEC cartel, an example of formal collusion among oil-producing countries, manipulates oil prices by controlling production levels. While this stabilizes global oil markets, it often results in higher prices for consumers and governments worldwide.

World Around Us: Oligopoly in the Soft Drink Industry

The global soft drink industry is dominated by two major players: Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. These firms control the majority of the market share, and their actions largely determine the market’s dynamics. This oligopolistic structure leads to various tradeoffs for consumers and firms.

Market Control and Pricing Power

- Fact: Coca-Cola and PepsiCo together control around 60% of the global soft drink market, with Coca-Cola leading at 44% and PepsiCo at 16% (as of 2020).

- Pricing Power: Both companies have substantial pricing power due to their brand strength and market dominance. They rarely engage in price competition, which allows them to keep prices relatively high.

- Impact on Consumers: While consumers benefit from a wide variety of beverages, they often pay more than in markets with more competition.

Innovation and Advertising

- Fact: Coca-Cola and PepsiCo spend billions annually on advertising and marketing. In 2020, Coca-Cola spent over $4 billion on advertising, while PepsiCo spent around $2.5 billion.

- Positive Impact: Heavy advertising leads to brand recognition, new product launches, and improvements in packaging and flavors.

- Negative Impact: A significant portion of the cost of a soft drink goes to advertising, not production efficiency, leading to inflated prices for consumers.

Barriers to Entry

- Fact: Coca-Cola and PepsiCo maintain high barriers to entry for new competitors through extensive distribution networks, exclusive bottling agreements, and strong brand loyalty.

- Impact: Smaller firms find it difficult to enter the market, leading to less competition and reduced innovation from new players. Consumers have fewer choices and often must choose between the two giants.

Collusion and Competitive Practices

- Fact: Although direct collusion between Coca-Cola and PepsiCo has not been legally proven, they engage in “non-price competition,” focusing on advertising, product differentiation, and promotional deals rather than lowering prices.

- Impact on Consumers: Consumers benefit from product variety but face stable, relatively high prices due to the lack of price competition between these two dominant firms.

Important Facts and Figures

- Coca-Cola’s Market Share (2020): 44% globally in the non-alcoholic beverage market.

- PepsiCo’s Market Share (2020): 16% globally.

- Advertising Expenditure (2020): Coca-Cola: $4 billion; PepsiCo: $2.5 billion.

- Global Soft Drink Market Size (2021): $856 billion, expected to grow at a CAGR of 5.2% through 2028.

Summary

Oligopolies present a mixture of benefits and drawbacks for both consumers and firms. While they foster innovation and provide product variety, they also lead to higher prices, reduced competition, and potential inefficiencies. The soft drink industry, dominated by Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, exemplifies these tradeoffs, as consumers enjoy a vast array of products but face higher prices and limited choices due to the dominance of these two firms.

References

- Coca-Cola and PepsiCo Market Shares: Statista

- OPEC and Oil Market Control: OPEC Official Site

- Advertising Data for Coca-Cola and PepsiCo: Annual Reports

Why Brands Choose High Prices and Earn Uneven Profits

Brands, particularly in oligopolistic markets, often choose high prices for several strategic reasons. Here’s why they don’t always lower prices to benefit consumers, even though it may seem like a path to attracting more customers:

1. Profit Maximization

- Primary Goal: Brands aim to maximize profits, not just sales volume. In oligopolies, companies know that lowering prices could trigger a price war, reducing everyone’s profits. Higher prices allow them to earn substantial profits, even if the number of consumers is lower.

- Example: In the luxury goods industry, brands like Gucci and Louis Vuitton charge high prices to maintain exclusivity and high margins. Their focus is on premium customers, not mass consumers.

2. Brand Positioning and Perception

- Reason: High prices are often associated with higher quality and brand prestige. Lowering prices could damage the brand’s image and make the product seem less valuable.

- Example: Apple charges premium prices for its iPhones, positioning the brand as innovative and exclusive. Lowering prices could dilute the brand’s reputation as a leader in technology and quality.

3. Barriers to Entry and Competition

- Oligopoly Advantage: In an oligopolistic market, the few firms that dominate are aware that they are not in a fiercely competitive environment like perfect competition. They can maintain higher prices because they have established barriers to entry, such as brand loyalty, technology, and distribution networks, which prevent new competitors from easily entering and undercutting them.

- Example: In the global airline industry, firms often charge higher prices due to limited competition on specific routes, even though lowering prices could attract more customers.

4. Risk of Price Wars

- Danger: Lowering prices can lead to price wars, where firms continuously undercut each other to attract consumers. This reduces overall profitability for all firms in the market.

- Example: In the telecom industry, companies like AT&T and Verizon avoid drastic price cuts, as it could initiate a price war, hurting both companies’ profits. Instead, they compete through differentiated services.

5. Fixed Costs and Economies of Scale

- Cost Consideration: Many firms in oligopolistic markets have high fixed costs (e.g., R&D, marketing, infrastructure). To cover these costs and achieve profitability, they charge higher prices. Lowering prices might not generate enough revenue to cover these expenses.

- Example: In the pharmaceutical industry, companies charge high prices for patented drugs because of the huge upfront costs of developing, testing, and marketing new drugs.

6. Inelastic Demand

- Consumer Behavior: In some industries, demand is relatively inelastic, meaning consumers are not very sensitive to price changes. This allows firms to charge high prices without losing a significant number of customers.

- Example: Cigarette companies know that demand for cigarettes is inelastic due to addiction, so they can maintain high prices without fearing a massive loss in customers.

Why Oligopolistic Firms Don’t Always Lower Prices to Increase the Number of Consumers

1. Fear of Diluting Brand Value

- Risk: For many brands, particularly in luxury or premium sectors, lowering prices could damage their image of exclusivity. This could alienate their core customer base and harm the brand in the long term.

- Example: Luxury car brands like BMW or Mercedes-Benz maintain high prices to preserve the prestige and exclusivity associated with owning their vehicles.

2. Limited Profit Margins

- Reason: Lower prices mean smaller profit margins. Companies must sell significantly more units to compensate for the lower price per unit, which may not always be feasible.

- Example: In the smartphone industry, companies like Apple or Samsung would need to sell far more units to maintain the same level of profit if they lowered prices. This is particularly difficult when the market is already saturated.

3. Consumer Loyalty and Price Insensitivity

- Loyal Customers: Brands rely on a loyal customer base that is willing to pay premium prices for perceived value. Lowering prices might not necessarily increase the number of consumers if the current customer base is stable and unresponsive to price changes.

- Example: Starbucks charges premium prices for coffee because their customers are willing to pay for the experience and brand, even when cheaper alternatives exist.

4. Non-Price Competition

- Alternative Strategy: In oligopolistic markets, companies often compete on factors other than price, such as product quality, innovation, customer service, and brand loyalty. Lowering prices isn’t always seen as the best strategy to attract more consumers.

- Example: In the automobile industry, companies compete on safety features, design, and innovation rather than price. Lowering prices could reduce their ability to invest in these differentiating factors.

Summary

Brands choose high prices and uneven profits because of the need to maximize profits, maintain brand perception, and avoid the risks associated with price wars. In oligopolistic markets, where few firms dominate, the focus is often on innovation, brand loyalty, and non-price competition. Lowering prices could damage their market position, reduce profitability, and dilute their brand value. Hence, firms often prioritize profit margins and brand strength over attracting a larger consumer base through lower prices.

References

- Luxury Market Strategies: McKinsey Report on Luxury Brands and Pricing

- Oligopolies in Telecom Industry: Statista

- Pricing Strategies in the Airline Industry: IATA Reports

World Around Us: Pharmaceutical Industry

The pharmaceutical industry is a prime example where oligopoly leads to higher prices. The market for certain drugs, especially patented medications, is often dominated by a few large firms. Once a pharmaceutical company develops a drug and obtains a patent, it gains significant market power. Competitors are restricted from producing similar products until the patent expires, which can result in monopolistic pricing during the patent period.

Facts and Figures:

In the U.S., for instance, the price of insulin—a drug used by millions of diabetics—has risen dramatically in recent years. Three companies (Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk) control 99% of the global insulin market. Between 2002 and 2013, the price of insulin tripled, contributing to public outcry over unaffordable healthcare costs.

Outcome: The limited competition and high barriers to entry (due to patents and regulations) allow firms in oligopolistic markets to set higher prices, which consumers must pay, often leading to public disagreement and regulatory scrutiny.

Reference: The rising price of insulin is documented in studies published by the American Diabetes Association and various research articles highlighting the control that a few firms exert over this critical drug market.

Innovation and Product Variety

Positive Tradeoff:

Although higher prices are a downside of oligopolies, these markets often foster innovation and product variety. Because firms in an oligopoly cannot solely rely on price competition, they invest heavily in research and development (R&D) to create differentiated products that stand out from competitors. This innovation is critical in sectors where consumers demand cutting-edge technology and unique features.

World Around Us: Tech Industry

The smartphone industry, dominated by giants like Apple and Samsung, is an example of how oligopolies can drive innovation. These firms compete fiercely by introducing new technologies, features, and designs. Every year, consumers expect advanced capabilities, such as improvements in camera technology, processing power, and software integration.

Facts and Figures:

Apple spent $27.5 billion on R&D in 2021 alone, focusing on developing new products like the iPhone, iPad, and other technologies. Samsung similarly invested $19.2 billion in R&D in 2021, continually pushing the boundaries of smartphone innovation.

Outcome: This innovation provides consumers with a variety of choices in terms of features, design, and technology. While consumers may pay higher prices, they benefit from having access to cutting-edge products and a wider selection than in more competitive or monopolistic markets.

Reference: The constant push for innovation in the tech sector has been well-documented, with firms striving to stay ahead of the competition through continuous product development. The competition between Apple and Samsung exemplifies how innovation thrives in oligopolistic markets.

Summary

In summary, the tradeoffs of imperfect competition in oligopolies are evident through both higher prices and increased innovation. Consumers may face higher costs due to the lack of intense price competition, but they also benefit from enhanced product differentiation and technological advances. The pharmaceutical and tech industries serve as clear examples of these dynamics, where market power leads to both challenges and opportunities for consumers.

Oligopoly through the Lens of Behavioral Economics

In an oligopoly, a few firms dominate the market, leading to unique behavioral patterns in both firms and consumers. Behavioral economics sheds light on how these firms and consumers make decisions that aren’t purely rational, as traditional economics might suggest. Let’s examine a case study to explore this further.

Case Study: Airline Industry and Behavioral Economics

In the airline industry, a few major firms control the majority of market share. In the U.S., airlines such as American, Delta, and United Airlines dominate. Similarly, in Europe, the market is controlled by a few giants like Ryanair, Lufthansa, and British Airways.

Constant Tension:

These firms are in constant tension between competing and colluding, especially in terms of pricing strategies. Although traditional economics would suggest that these companies set prices based solely on supply and demand, behavioral economics shows that other factors come into play, like consumer biases, firm reputation, and pricing psychology.

Behavioral Concepts at Play

Anchoring Bias and Price Setting

Consumer Expectations: Consumers often anchor their expectations about flight prices based on past experiences. Airlines take advantage of this by using price anchoring in their advertisements. They may show a high price first and then offer a “discount,” even if the discount is close to the regular price.

Fact: A study conducted by MIT found that consumers’ willingness to pay for tickets is influenced more by the way prices are presented than the actual cost itself (MIT, 2017).

Loss Aversion

Additional Fee: Airlines charge additional fees for services like seat selection, baggage, and meals. This pricing strategy taps into consumers’ loss aversion—the fear of losing out on certain comforts or convenience leads them to pay extra.

Fact: In 2022, airlines worldwide made over $50 billion from these additional fees alone, reflecting how consumer behavior can be influenced by loss aversion (IATA, 2022).

Nudge Theory

Nudging: Some airlines nudge consumers into buying premium services by default. For example, when booking a flight, the most expensive options (like business class or extra legroom) are pre-selected, encouraging consumers to spend more without fully realizing their decision.

Fact: According to a study by Richard Thaler (2019), nudging strategies in the airline industry can increase revenue by as much as 15%.

World Around Us: Ryanair and Pricing Strategies

- Pricing Strategy: Ryanair, a low-cost European airline, employs behavioral pricing strategies to maintain its market dominance. By offering low base prices but charging for every extra service (like baggage and seat selection), Ryanair taps into consumer biases, including loss aversion and present bias (preferring a cheap ticket now, even if additional costs arise later).

- Fact: In 2020, Ryanair generated €2.2 billion in ancillary revenues, accounting for nearly 40% of its total revenue.

Summary

In the airline industry, behavioral economics provides insights into why and how oligopolistic firms set prices, package services, and encourage consumer spending. Behavioral pricing strategies—such as using loss aversion, anchoring bias, and nudges—allow firms to maximize profits, even when there is fierce competition.

Game Theory and Behavioral Economics in OPEC Pricing Strategies

Game theory studies how firms make decisions in competitive and cooperative environments. When combined with behavioral economics, it helps predict real-world behaviors influenced by biases, trust, and emotions. Here’s how this applies to OPEC and similar oligopolies:

OPEC as an Oligopoly

- OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) controls a large share of global oil production.

- Members cooperate to set oil production levels, which influence global oil prices.

- However, individual members sometimes face incentives to cheat by overproducing to gain more revenue.

Game Theory in OPEC

- Prisoner’s Dilemma: Each member faces a choice to cooperate (limit production) or defect (overproduce). Cooperation benefits the group but requires trust.

- Nash Equilibrium: If all members assume others will cheat, they may overproduce, leading to lower global oil prices and profits for all.

Behavioral Economics Insights

- Behavioral economics explains why OPEC members may still cooperate despite incentives to cheat:

- Loss Aversion: Members fear losing the long-term benefits of cooperation more than gaining short-term revenue.

- Reciprocity: Members may punish cheating countries by overproducing themselves, and maintaining discipline.

- Framing Effects: OPEC often frames cooperation as a shared success story, encouraging compliance.

Pricing Strategies

- OPEC uses production quotas to manage supply and stabilize prices. Game theory predicts:

- Tit-for-Tat Strategy: If one member cheats, others retaliate by increasing production, ensuring long-term cooperation.

- Sequential Games: Larger members, like Saudi Arabia, act as leaders. They cut production first to signal commitment, influencing others to follow.

Case Studies

2014-2016 Oil Price War:

- Saudi Arabia increased production to maintain market share against U.S. shale oil.

- Game theory showed a shift from cooperation to competition when trust broke down.

COVID-19 Pandemic (2020):

- OPEC+ (including Russia) agreed to historic production cuts to stabilize prices.

- Behavioral insights like loss aversion motivated members to cooperate under severe economic pressure.

Application Beyond OPEC

- Airline Alliances: Competing airlines collaborate to manage capacity and prices.

- Telecom Industries: Firms use game theory to predict competitor pricing and promotions, balancing cooperation and competition.

Summary

Game theory explains how oligopolies like OPEC set pricing strategies under competitive pressures. Behavioral economics adds depth by recognizing human biases and emotions, improving predictions about cooperation and cheating. Together, these tools help policymakers and firms understand market dynamics better.

Research Suggestions for Economists

- Behavioral Pricing Strategies in Oligopolies

Study how firms use tactics like nudging and anchoring to influence consumer spending in oligopolistic markets. What are the ethical issues associated with these practices?

- Loss Aversion and Consumer Spending in Oligopolies

Analyze the role of loss aversion in consumer decisions within oligopolistic industries such as airlines, telecom, or tech. How can companies balance making profits while keeping customers satisfied?

- Impact of Anchoring in Price Wars

Explore how price anchoring affects competition and potential collusion in oligopolies. Does consumer psychology help stabilize prices or create more volatility?

- Behavioral Nudges and Market Efficiency

Investigate whether behavioral nudges in oligopolistic markets enhance or harm market efficiency. Are consumers making better decisions, or are they being manipulated?

- Technology’s Role in Disrupting Oligopolies

Study how emerging technologies, such as electric vehicles and renewable energy, disrupt traditional oligopolies in established industries.

- Government Regulation’s Impact on Oligopolies

Examine how different regulatory environments across countries influence the behavior and strategies of firms in oligopolistic markets.

- Consumer Behavior in Oligopolies

Focus on the impact of brand loyalty and consumer inertia on competitive strategies in the markets like smartphones.

- Price Stickiness and Behavioral Factors in Oligopolies

Explore how psychological elements, like loss aversion and herd behavior, contribute to price rigidity explained by the kinked demand curve in oligopolies.

- Perceived Fairness and Pricing in Oligopolies

Research how consumers’ perceptions of fairness influence their reactions to price change in oligopolistic markets.

- Game Theory, Behavioral Insights, and OPEC Pricing

Analyze how game theory, combined with behavioral economics, can predict pricing strategies in OPEC and other similar oligopolies.

- Behavioral Factors in Collusion

Investigate how behavioral economics, including biases like overconfidence and risk aversion, affects firms’ decisions to collude or compete in oligopolistic markets.

- Tacit Collusion in Oligopolies

Study how firms signal intentions to competitors without explicit agreements, focusing on behavioral economics’ role in tacit collusion.

- Game Theory and Irrational Behavior

Examine how game theory models change when irrational behaviors, like fairness concerns and bounded rationality, are considered.

- Impact of Digital Platforms on Oligopolies

Analyze how digital platforms and algorithms influence competition and collusion. Does algorithmic pricing promote tacit collusion?

- Cultural Differences and Competition in Oligopolies

Explore how cultural variations in risk-taking, trust, and cooperation impact competition and collusion in oligopolistic markets, especially in Asia.

- Innovation Patterns in Oligopolies

Investigate how the structure of oligopolistic markets affects innovation compared to more competitive or monopolistic markets. Do oligopolies drive innovation effectively?

- Regulation and Pricing Behavior in Oligopolies

Examine the impact of government regulations, such as patent laws, on pricing behavior in oligopolistic industries like pharmaceuticals.

- Cross-Cultural Analysis of Oligopolistic Behavior

Study how oligopolistic behavior varies across regions and cultures, with a focus on pricing and innovation differences between Eastern and Western markets.

- Consumer Welfare in Oligopolistic Markets

Research how consumer welfare is affected by the tradeoff between high prices and increased innovation in oligopolies. Can policies balance these factors for better consumer outcomes?

- Price Elasticity and Market Power in Oligopolies

Study how demand elasticity and market power shape consumer behavior, particularly in essential sectors like healthcare and technology.

Critical Thinking

- How do oligopolies differ from perfect competition and monopoly markets, in terms of pricing and output decisions?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages for consumers in an oligopolistic market structure?

- Why do firms in oligopolies often avoid price wars, and what alternative competitive strategies do they use?

- How do barriers to entry help sustain oligopolies in industries like telecommunications and airlines?

- In what ways can government regulation both support and undermine the stability of oligopolies?

- How do concepts like game theory and the Prisoner’s Dilemma apply to decision-making among firms in oligopolies?

- What role does consumer brand loyalty play in sustaining oligopolies, particularly in industries like technology and automotive?

- How can price rigidity, such as explained by the kinked demand curve, maintain stability in oligopoly markets even during economic fluctuations?

- What are the ethical implications of collusion, both tacit and explicit, among oligopolistic firms?

- How do cultural and regional differences impact the behavior of oligopolies in different parts of the world?

- Can oligopolies drive innovation more effectively than competitive markets due to their larger resources, or do they stifle it through collusion?

- In what ways do oligopolistic firms manipulate consumer psychology through advertising and pricing strategies?

- How does the introduction of new technologies disrupt established oligopolies, and what strategies do incumbents use to maintain market control?

- To what extent can digital platforms and algorithmic pricing foster collusion in modern oligopolies?

- How can public policy balance the trade-off between fostering innovation in oligopolistic markets and protecting consumers from high prices?

- In a duopoly, Firm A and Firm B face a market demand curve: Q=100-P, where Q is the quantity demanded and P is the price. Firm A sets a price of $40. Calculate Firm A’s quantity sold and its total revenue.

- In an oligopolistic market, there are four firms: Firm A (30% market share), Firm B (25% market share), Firm C (20% market share), and Firm D (25% market share). If the total market is worth $1,000,000, calculate Firm A’s revenue.

- Three firms in an oligopoly form a cartel and agree to set a price of $50 per unit. If the total market demand at this price is 600 units, and the firms share the market equally, how many units will each firm sell?

- Firm A in an oligopolistic market has a fixed cost of $500 and a variable cost of $20 per unit produced. If the firm produces 100 units, calculate the total cost.

- In an oligopoly, the price elasticity of demand for a product is -2. If the firm increases the price by 10%, by what percentage will the quantity demanded change?

2 Comments