A monopoly is a market structure where a single firm controls the entire market. This firm is the sole producer of a product or service, and there are no close substitutes. Now, we are going to explore the world of monopolies. We’ll study how monopolies emerged historically, what they are, and their impact on economies.

Historical Emergence of Monopolies

Early Monopolies

Ancient Times: Monopolies have existed for centuries. In ancient Rome, the government monopolized salt production, recognizing its importance for preservation and its role as a valuable trading commodity. This allowed the government to control both supply and prices, which ensured a steady revenue stream.

Medieval Period: During medieval times, monarchs granted exclusive rights to certain merchants and guilds, allowing them to dominate specific trades. A notable example is the East India Company, established by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600, which was given a monopoly over trade in the East Indies. This monopoly allowed the company to control trade routes, dictate prices, and accumulate significant wealth and power.

Industrial Revolution

Technological Advances: The 19th century saw the rise of large industrial monopolies due to technological advancements and the ability to control large-scale production. These monopolies often emerged in industries where economies of scale were significant.

Example: In the United States, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil controlled about 90% of the oil refining industry by the late 1800s. This dominance was achieved through aggressive business tactics, including buying out competitors and securing favorable rates from railroads.

How These Monopolies Ended

Monopolies such as those held by the East India Company and Standard Oil eventually ended due to various factors that disrupted their sole ownership of resources:

1. Government Intervention:

Antitrust Laws: In the United States, the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was enacted to combat monopolistic practices. This led to the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911 into 34 smaller companies.

Nationalization: Some monopolies were ended by government nationalization. For example, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British government took direct control over the territories and resources previously managed by the East India Company, effectively dissolving its monopoly.

2. Technological and Market Changes:

Innovation: New technologies can disrupt existing monopolies by introducing new ways of producing or delivering products. The rise of alternative energy sources, for instance, reduced the dominance of oil monopolies.

Competition: Over time, new entrants can erode a monopoly’s market share. Improved transportation and communication have made it easier for new companies to enter and compete in various markets.

Regulation and Legal Challenges:

Regulatory Reforms: Governments have introduced regulations to prevent monopolistic practices and encourage competition. For example, the breakup of AT&T in 1982 was driven by regulatory reforms aimed at increasing competition in the telecommunications industry.

Legal Challenges: Monopolies have faced legal challenges from competitors, consumers, and government agencies. These challenges often result in court rulings that limit or dissolve monopolistic practices.

Economic Shifts:

Globalization: Increased global trade has exposed monopolies to international competition, making it harder for them to maintain their dominance. Companies in previously protected markets now face competition from foreign firms with different competitive advantages.

Market Saturation: As markets mature and saturate, monopolies can find it difficult to sustain their dominance. The need to innovate and adapt to changing consumer preferences can open opportunities for new competitors.

Summary

Understanding the historical emergence and eventual decline of monopolies provides valuable insights into the dynamics of market power and competition. These lessons are crucial for policymakers, economists, and business leaders as they navigate the complexities of modern economies and strive to promote fair and competitive markets.

Natural Monopoly vs. Legal Monopoly

The control of a physical resource can lead to different types of monopolies, which can be categorized as natural or legal monopolies. Understanding the difference between a natural monopoly and a legal monopoly is crucial in the study of economics, particularly when analyzing market structures and regulatory policies. Let’s delve into each concept with in-depth explanations and real-world examples.

1. Natural Monopoly

A natural monopoly occurs when a single firm can supply the entire market’s demand at a lower cost than multiple competing firms. This typically happens in industries with high fixed costs and low marginal costs, making competition impractical and inefficient.

Key Characteristics:

- High Fixed Costs: Industries require substantial infrastructure and investment that cannot be easily duplicated.

- Economies of Scale: The average cost of production decreases as the firm expands, making it more efficient for one company to produce all of the output.

- Natural Barriers to Entry: The cost advantages of a single supplier prevent new firms from entering the market.

World Around Us: Natural Monopoly

Utility Services:

Electricity Supply: In many regions, a single company often manages electricity distribution due to the high cost of infrastructure (power plants, transmission lines). For instance, in the United States, Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) serves a large portion of California’s electricity needs.

Water Supply: Water utilities are typically natural monopolies because of the extensive infrastructure required. For example, Thames Water in the UK provides water and wastewater services to millions of customers.

Public Transportation:

Subway Systems: Large cities often have a single company operating their subway systems. For example, the London Underground is managed by Transport for London (TfL), which operates the entire network.

Standard Oil:

Background: In the late 19th century, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company controlled about 90% of the oil refining industry in the United States. This control was achieved through horizontal integration, where the company bought out competitors and controlled key resources like oil fields.

Impact: Standard Oil’s dominance was based on its ability to control crucial physical resources (oil fields and refineries) and achieve economies of scale, resulting in lower production costs that competitors could not match.

Regulation:

Natural monopolies are usually subject to government regulation to prevent abuse of market power and ensure fair pricing. Regulators may set price caps or control the quality of service.

2. Legal Monopoly

A legal monopoly is granted by the government through legislation, patents, or exclusive rights, allowing a single firm or entity to operate without competition in a particular market. These monopolies are created to encourage innovation, protect national interests, or control essential services.

Key Characteristics:

- Government Grant: The monopoly status is legally conferred and can be for specific periods or indefinitely.

- No Competition: The legal framework prevents other firms from entering the market.

- Purpose Driven: Often established to promote innovation, protect public interests, or maintain control over critical resources.

World Around Us: Legal Monopolies

Patents and Intellectual Property:

Pharmaceutical Companies: Companies like Pfizer hold patents on specific drugs, giving them exclusive rights to produce and sell those drugs. For example, Pfizer’s patent on Viagra created a legal monopoly on this erectile dysfunction medication for many years.

Technology Patents: Companies like Apple have patents on their unique technologies and designs, providing them with exclusive rights to manufacture and sell their innovations.

Government Grants and Licenses:

Postal Services: In many countries, the national postal service is a legal monopoly. For example, the United States Postal Service (USPS) has exclusive rights to deliver mail within the US.

Public Broadcasting: In some countries, public broadcasters are granted monopoly rights to broadcast television and radio. For instance, the BBC in the United Kingdom has a legal monopoly over public service broadcasting.

British East India Company:

Background: The British East India Company, established in 1600, was granted a monopoly over trade in the East Indies by Queen Elizabeth I. This legal monopoly allowed the company exclusive trading rights in the region.

Impact: The monopoly facilitated significant profits and control over trade routes and resources, but it also led to exploitative practices and economic dominance over local markets, contributing to the eventual British colonial rule in India.

Regulation and Oversight:

Legal monopolies are often regulated to balance public interest and prevent the abuse of power. For instance, patents have time limits, and monopoly rights for certain services can be revoked or put under scrutiny if they fail to serve the public interest.

Comparative Analysis: Natural Monopoly vs. Legal Monopoly

| Aspect | Natural Monopoly | Legal Monopoly |

| Basis | Economic conditions and market structure | Legal provisions and government grants |

| Entry Barriers | High due to cost and scale economies | Legal barriers created by laws or regulations |

| Purpose | Cost efficiency and service provision | Innovation encouragement, public interest protection |

| Examples | Utilities, railways, water supply | Patented drugs, national postal services, public media |

| Regulation | Typically regulated to prevent abuse of power | Often regulated to ensure compliance with public interest |

Summary

Understanding the distinction between natural and legal monopolies helps in comprehending how different markets are structured and regulated. While natural monopolies arise from economic factors, legal monopolies are created through government action. Both types require careful regulation to ensure they serve the public interest without stifling competition or innovation.

By exploring these examples and characteristics, we gain insights into how different markets operate and how policymakers can effectively manage and regulate these entities.

Barriers to Entry in a Monopoly Structure

Barriers to entry are obstacles that make it difficult or impossible for new firms to enter a market. These barriers protect monopolies from competition and help maintain their market dominance. Here are some common barriers to entry in a monopoly structure:

- Legal Barriers

- Control of Essential Resources

- Economies of Scale

- Technological Superiority

- High Capital Requirements

- Network Effects

- Strategic Actions by the Monopoly

- Brand Loyalty

- Government Regulations

1. Legal Barriers

Patents: Patents grant exclusive rights to produce and sell a product or use a process for a certain period, usually 20 years. This legal protection prevents other firms from entering the market.

Example: Google has maintained its patent right monopoly for more than a decade.

Licenses and Permits: Governments may require firms to obtain licenses or permits to operate in certain industries, which can be difficult and costly to acquire.

Example: In many countries, only licensed companies can provide utilities like water and electricity.

2. Control of Essential Resources

When a firm controls a resource necessary for production, it can prevent other firms from accessing it.

Example: De Beers controlled most of the world’s diamond mines, making it difficult for other companies to enter the diamond market.

3. Economies of Scale

Large firms often experience lower per-unit costs due to high production volumes. This cost advantage makes it hard for smaller, new entrants to compete.

Example: Large tech companies like Amazon benefit from economies of scale, making it difficult for small e-commerce startups to compete on price.

4. Technological Superiority

A firm that possesses advanced technology can produce goods more efficiently, making it difficult for competitors to match their cost and quality.

Example: Intel’s advanced semiconductor technology gives it a competitive edge in the microprocessor market.

5. High Capital Requirements

The need for significant investment to enter a market can deter new firms. This includes the cost of machinery, infrastructure, and research and development.

Example: The automotive industry requires substantial capital investment, making it difficult for new firms to enter the market.

6. Network Effects

When the value of a product increases with the number of users, it creates a barrier to entry because new firms struggle to attract users away from an established network.

Example: Social media platforms like Facebook benefit from network effects, making it hard for new entrants to attract a critical mass of users.

7. Strategic Actions by the Monopoly

Established firms might engage in practices like predatory pricing (temporarily lowering prices to drive competitors out) or exclusive contracts with suppliers and distributors to prevent new entrants.

Example: Microsoft faced antitrust lawsuits for bundling its Internet Explorer browser with its Windows operating system, making it hard for other browsers to compete.

8. Brand Loyalty

Strong brand loyalty can deter new entrants, as consumers are less likely to switch to a new or unknown brand.

Example: Coca-Cola’s strong brand loyalty makes it difficult for new soft drink companies to gain market share.

9. Government Regulations

Regulations can create barriers by imposing standards and requirements that are costly for new firms to meet.

Example: The pharmaceutical industry is heavily regulated, with rigorous testing and approval processes that new firms must navigate to bring a product to market.

Summary

Understanding these barriers to entry is crucial for analyzing why monopolies can maintain their market dominance and why competition is limited in certain industries. By recognizing these barriers, policymakers and economists can better address the challenges associated with monopolistic markets and work towards promoting fair competition.

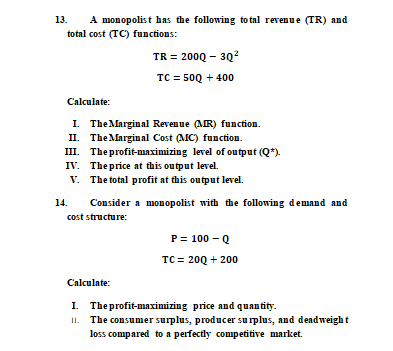

Natural Monopoly with Economies of Scale

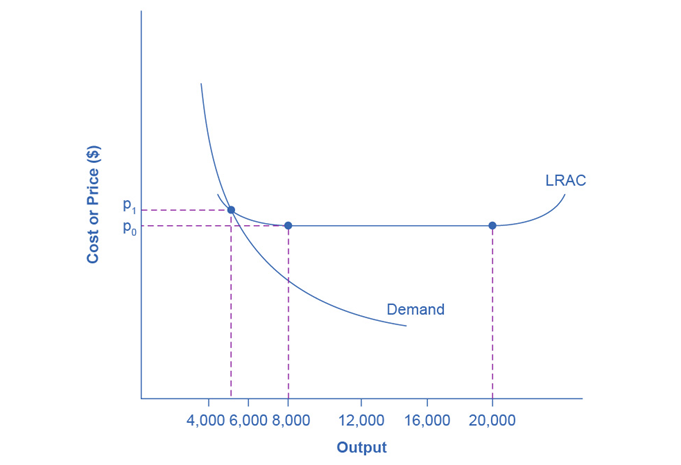

To comprehend how a natural monopoly arises, it’s essential to explore the concepts of economies of scale and how they interact with market demand. The provided diagram helps illustrate this interaction.

Long-Run Average Cost Curve and Market Demand

The graph illustrates the long-run average cost (LRAC) curve and the market demand curve for an industry such as airplane manufacturing.

- Axes:

- The y-axis represents price and cost.

- The x-axis represents the output (quantity of planes produced).

- Long-Run Average Cost (LRAC) Curve:

- The LRAC curve is U-shaped.

- It shows economies of scale (decreasing costs) up to 8,000 planes per year (price P0). Hence average costs decrease as production increases

- Constant returns to scale (costs stable) between 8,000 and 20,000 planes. The firm’s average costs remain constant.

- Diseconomies of scale (increasing costs) beyond 20,000 planes. The firm experiences increasing average costs.

- Market Demand Curve:

- The demand curve intersects the LRAC curve at an output level of 5,000 planes per year and at a price P1, which is higher than P0.

Implications of the Intersection:

- Single Producer: Given the market demand of 5,000 planes, only one firm can efficiently supply the market. Producing at this level is less costly per unit compared to a scenario where multiple firms compete.

- Entry Barrier: If a second firm tries to enter at a smaller size (e.g., 4,000 planes), its costs will be higher than the incumbent firm, making it uncompetitive.

- Inefficiency of Multiple Firms: A second firm entering at a larger scale (e.g., 8,000 planes) would face the issue of insufficient market demand to sell all produced planes, leading to inefficiency.

World Around Us: Natural Monopolies

Utilities:

- Electricity Supply: Once the infrastructure is in place, the marginal cost of serving an additional customer is low. For instance, Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) in California.

- Water Supply: After laying the main water pipes, adding another home is relatively cheap. Thames Water in the UK is an example.

Transportation:

- Subway Systems: One company often operates the entire network efficiently, like Transport for London (TfL) with the London Underground.

Local Markets:

- Cement Production: Due to high transportation costs and local demand, a single plant often serves a region efficiently.

Characteristics of a Natural Monopoly:

- High Fixed Costs: Significant initial investment in infrastructure.

- Low Marginal Costs: Adding an additional customer is relatively cheap.

- Economies of Scale: Lower average costs with increased production up to a certain point.

Summary

Natural monopolies occur due to the cost advantages associated with economies of scale, making it inefficient for multiple firms to operate in the market. They often arise in industries with substantial infrastructure requirements and low marginal costs, such as utilities and certain local markets. Understanding these dynamics helps explain why some markets are best served by a single provider and why regulation is often necessary to ensure fair pricing and prevent abuse of monopoly power.

Demand Curves Perceived by a Perfectly Competitive Firm vs by a Monopoly

Understanding the differences in the demand curves perceived by perfectly competitive firms and monopolies is essential in economics. These curves illustrate how each type of firm perceives its ability to influence market prices and quantities.

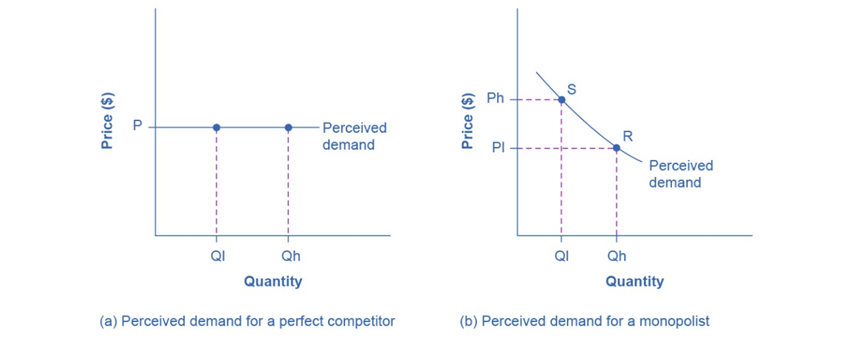

Figure 11.2 (a): This figure illustrates the demand curve for a perfectly competitive firm as a horizontal line at the market price (P). The firm can sell any quantity, from Ql (low quantity) to Qh (high quantity), at this price without affecting the market price.

Figure 11.2 (b): This figure shows the demand curve for a monopolist as a downward-sloping line. If the monopolist produces a high quantity (Qh), the price drops to Pl. Conversely, if it produces a low quantity (Ql), it can charge a higher price (Ph).

Here’s a comparison of the demand curves perceived by a perfectly competitive firm and a monopolist in tabular form:

| Aspect | Perfectly Competitive Firm | Monopolist |

| Shape of Demand Curve | Horizontal (perfectly elastic) | Downward-sloping |

| Price Setting Ability | Price taker: Cannot influence market price | Price maker: Can influence market price |

| Market Influence | Individual firm’s actions do not affect market price | Firm’s output decision affects market price |

| Elasticity of Demand | Perfectly elastic: Demand is highly sensitive to price changes | Less elastic: Demand is less sensitive to price changes |

| Quantity Sold at Market Price | Can sell any quantity at the prevailing market price | Must lower price to sell more quantity |

| Revenue Relationship | Marginal Revenue (MR) = Market Price (P) | Marginal Revenue (MR) < Price (P) |

| Example | Agricultural products (e.g., wheat, rice) in competitive markets | Utility companies (e.g., electricity, water) |

Explanation:

Shape of Demand Curve:

- Perfectly Competitive Firm: Faces a perfectly elastic (horizontal) demand curve, meaning it can sell any quantity at the market price without affecting the price.

- Monopolist: Faces a downward-sloping demand curve, indicating that to sell more, it must reduce the price.

Price Setting Ability:

- Perfectly Competitive Firm: Cannot influence the market price; it takes the price as given by market forces.

- Monopolist: Has the power to set prices by adjusting the quantity it produces.

Market Influence:

- Perfectly Competitive Firm: Its individual supply decisions do not impact the overall market price due to the presence of many other firms.

- Monopolist: Its production decisions directly impact the market price because it is the sole provider of the goods or services.

Elasticity of Demand:

- Perfectly Competitive Firm: Demand is highly elastic; any price increase would result in losing all customers to competitors.

- Monopolist: Demand is less elastic because there are no close substitutes for the monopolist’s product.

Quantity Sold at Market Price:

- Perfectly Competitive Firm: Can sell any quantity at the market price, as the price is determined by overall market supply and demand.

- Monopolist: Must lower the price to increase the quantity sold, reflecting the downward-sloping demand curve.

Revenue Relationship:

- Perfectly Competitive Firm: Marginal revenue equals the market price because each additional unit sold adds the same amount to total revenue.

- Monopolist: Marginal revenue is less than the price because selling additional units requires lowering the price of all units sold.

Example: Perfect Competition:

Agricultural Markets: In countries like India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, markets for basic crops like wheat, rice, and vegetables often resemble perfect competition. Numerous small farmers sell identical products, and no single farmer can influence the market price.

Example: Monopoly

Utility Companies: In many countries, utility companies (e.g., water, and electricity) operate as natural monopolies due to the high infrastructure costs involved. For instance, in the United States, local electricity providers often hold monopoly power in their regions.

Summary

The demand curves perceived by perfectly competitive firms and monopolies highlight their different market powers and pricing strategies. Perfectly competitive firms are price takers with a perfectly elastic demand curve, while monopolists are price makers with a downward-sloping demand curve. Understanding these differences helps in analyzing market behaviors and the impact of market structures on prices and outputs.

Marginal Revenue and Marginal Cost for a Monopolist

For a monopolist, the concepts of marginal revenue (MR) and marginal cost (MC) are crucial for determining the profit-maximizing level of output. Unlike a perfectly competitive firm, a monopolist has control over the price and must consider how changes in output affect the overall revenue and cost.

Task for You: Draw a diagram

A diagram illustrating this would show:

- The downward-sloping MR curve.

- The upward-sloping MC curve.

- The intersection point of MR and MC indicates the profit-maximizing quantity.

- The corresponding price is determined from the demand curve at this quantity.

By understanding these concepts and calculations, one can analyze how monopolists determine their optimal production and pricing strategies.

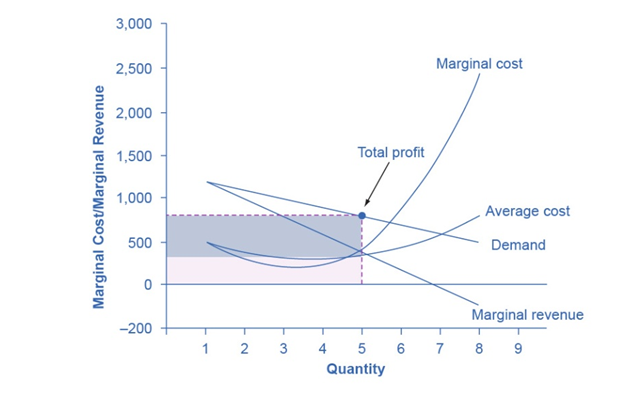

Reference Diagram: Marginal Revenue and Marginal Cost for the HealthPill Monopoly

Here is an example diagram presented below from the reference book for your convenience.

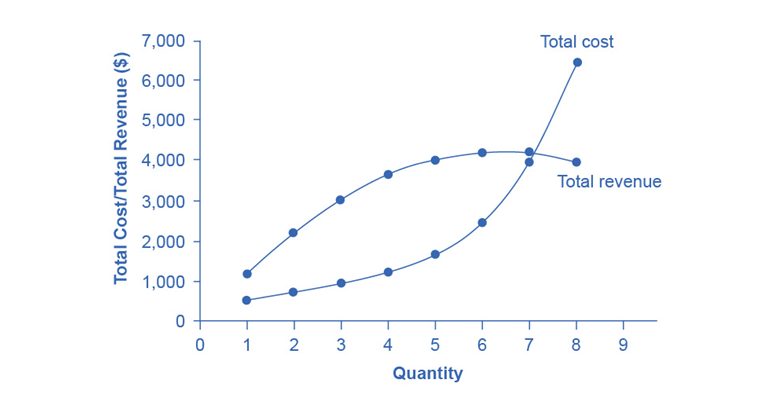

Figure 11.3 Total Revenue and Total Cost for the HealthPill Monopoly

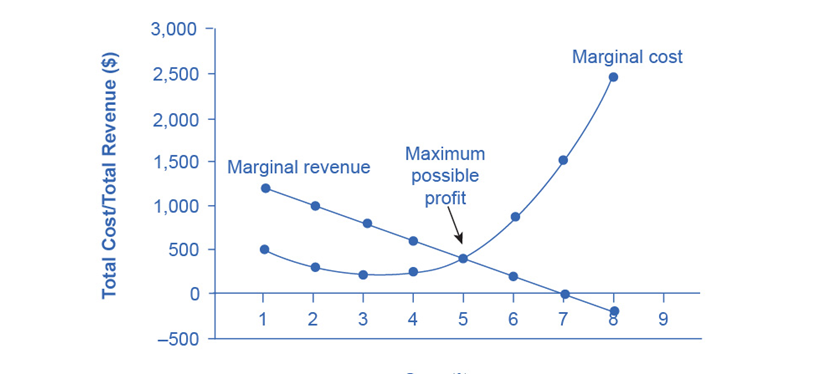

Figure 11.4 Marginal Revenue and Marginal Cost for the HealthPill Monopoly

Figure 11.5 Illustrating Profits at the HealthPill Monopoly

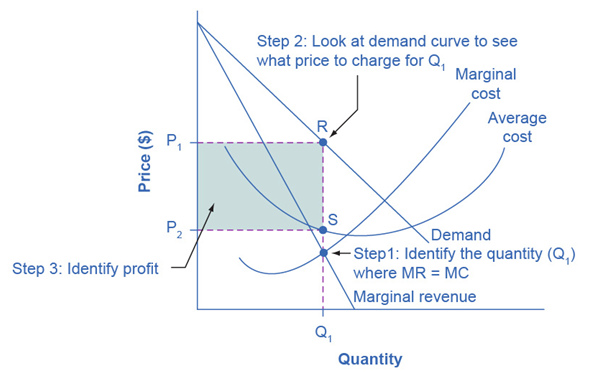

Monopolist Decision: 3-Step Procedure for Profit Calculation

Step 1: The Monopolist Determines Its Profit-Maximizing Level of Output

- Calculate Total Revenue (TR):

- Use the demand curve to find the price for each quantity.

- Calculate the total revenue for each quantity (TR = Price × Quantity).

- Calculate Marginal Revenue (MR):

- Derive the marginal revenue curve from the total revenue calculations.

- MR is the additional revenue gained from selling one more unit.

- Determine Profit-Maximizing Output (Q):*

- Set Marginal Revenue (MR) equal to Marginal Cost (MC) and solve for Q.

- This gives the quantity where profit is maximized.

Figure 11.6 How a Profit-Maximizing Monopoly Decides Price

Step 2: The Monopolist Decides What Price to Charge

- Identify the Profit-Maximizing Quantity (Q):*

- From the previous step, use the calculated Q*.

- Determine the Price (P):

- Draw a vertical line from Q* up to the demand curve.

- The point where this line intersects the demand curve gives the profit-maximizing price (P).

Step 3: Calculate Total Revenue, Total Cost, and Profit

- Calculate Total Revenue (TR):

- Total Revenue = Price (P) × Quantity (Q*).

- Represented as the area of the rectangle formed by P and Q* on the graph.

- Calculate Total Cost (TC):

- Use the Total Cost function (TC = Fixed Cost + Variable Cost).

- Calculate TC at Q*.

- Calculate Profit:

- Profit = Total Revenue (TR) – Total Cost (TC).

- Represented as the area above the cost curve and below the revenue line on the graph.

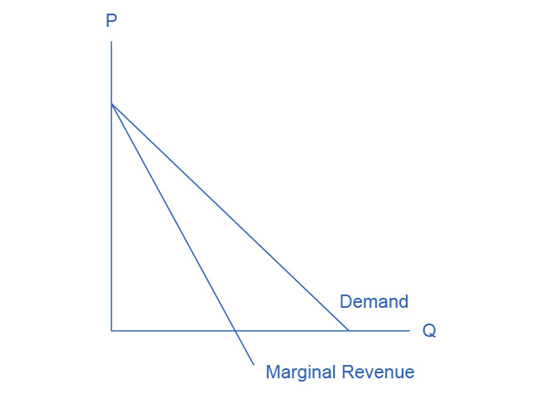

Monopolist’s Marginal Revenue Always less than the Price

In a monopoly, the marginal revenue (MR) is always less than the price (P) due to the downward-sloping demand curve that the monopolist faces. Here’s a detailed explanation:

1. Downward-Sloping Demand Curve

Demand Relationship: For a monopolist, the demand curve is downward-sloping. This means that to sell an additional unit, the monopolist must lower the price not just for that extra unit, but for all previous units as well.

2. Marginal Revenue Calculation

Total Revenue (TR): TR is calculated as P×Q, where P is the price and Q is the quantity sold.

Marginal Revenue (MR): MR is the additional revenue generated from selling one more unit of output. It is derived from the change in total revenue when the quantity sold increases by one unit.

3. Why MR is less than P

Price Reduction: To sell one additional unit, the monopolist must reduce the price across all units sold. This price reduction affects the total revenue.

- Price Effect vs. Quantity Effect:

Price Effect: Lowering the price decreases the revenue on all previous units.

Quantity Effect: Selling one more unit increases total revenue by the price of that unit.

- Result: The marginal revenue is the price effect minus the quantity effect, leading to MR being less than the price.

4. Graphical Representation:

- The demand curve slopes downward.

- The Marginal Revenue curve lies below the demand curve, starting from the same point on the y-axis but declining twice as steeply.

Figure 11.7 The Monopolist’s Marginal Revenue Curve versus Demand Curve

Summary

In summary, the monopolist’s marginal revenue is always less than the price because each additional unit sold reduces the price of all units sold, not just the last one. This leads to a downward-sloping marginal revenue curve that lies below the demand curve.

The Inefficiency of Monopoly

A monopoly faces both allocative and productive inefficiencies. Here’s a detailed explanation of each type:

1. Allocative Inefficiency

Allocative inefficiency occurs when the output level of a good or service is not socially optimal. In other words, the price consumers are willing to pay (which reflects the marginal benefit) does not equal the marginal cost of production.

Explanation:

- Price and Marginal Cost: In a perfectly competitive market, firms produce where the price (P) equals the marginal cost (MC), leading to allocative efficiency. However, a monopolist produces where marginal revenue (MR) equals marginal cost (MC), not where P equals MC.

- Consumer Surplus and Deadweight Loss: Because the monopolist sets a higher price and produces a lower quantity than would occur in a competitive market, there is a loss of consumer surplus and a deadweight loss to society. This deadweight loss represents the net benefit lost because the monopolist’s price exceeds the marginal cost of production.

2. Productive Inefficiency

Productive inefficiency occurs when a firm does not produce at the lowest possible cost.

Explanation:

- Average Cost Curve: In perfect competition, firms operate at the minimum point of their average cost curve in the long run. However, a monopolist may not produce at this point. Instead, they might operate at a higher average cost due to a lack of competitive pressure to minimize costs.

- Scale and X-Inefficiency: A monopolist might also suffer from X-inefficiency, which is inefficiency resulting from the lack of competitive pressure to control costs and operate efficiently.

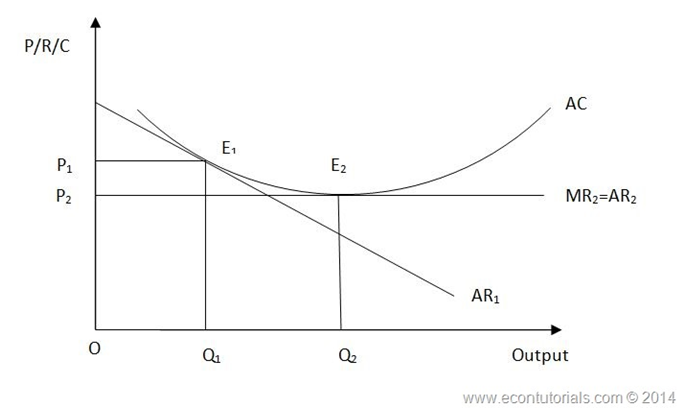

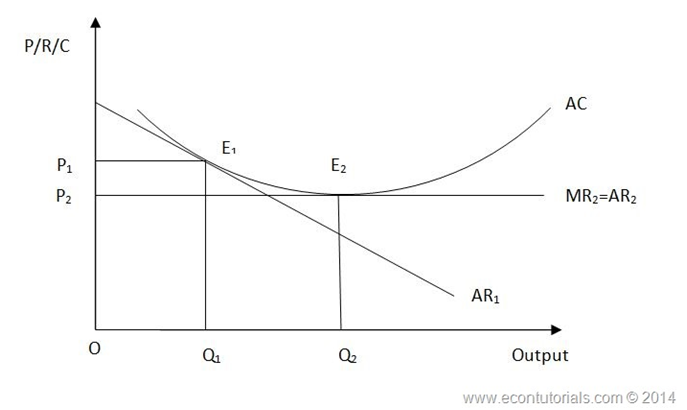

Graphical Representation of Monopoly Inefficiency

Let’s analyze the provided diagram to understand the inefficiency in a monopoly market:

Figure 11.8 Monopoly Inefficiency

- Axes and Curves:

- Y-Axis (P/R/C): Represents price, revenue, and cost.

- X-Axis (Output): Represents the quantity of output.

- AC Curve: Represents the Average Cost curve.

- AR Curve (Average Revenue): This is the demand curve for the monopolist.

- MR Curve (Marginal Revenue): The marginal revenue curve for the monopolist, which is always below the AR curve due to the downward-sloping demand.

- Key Points and Lines:

- E1: The equilibrium point where AR1 intersects AC, representing the price P1 and quantity Q1.

- E2: The equilibrium point where AR2 intersects AC, representing the price P2 and quantity Q2.

- Q1 and Q2: Output levels at different points on the average revenue curve.

- P1 and P2: Price levels corresponding to Q1 and Q2.

- Marginal Revenue and Average Revenue:

- The marginal revenue (MR) curve lies below the average revenue (AR) curve. This is because, in order to sell an additional unit, the monopolist must lower the price on all units sold, not just the additional one, leading to MR being less than AR.

- Efficiency Loss:

- Productive Inefficiency: The monopolist is not producing at the lowest point on the AC curve. Instead, it is producing at a higher cost per unit.

- Allocative Inefficiency: The monopolist’s price (P1 or P2) is above the marginal cost (MC); meaning consumers are paying more than the cost of producing the additional unit. This results in a deadweight loss, as the quantity produced (Q1 or Q2) is less than what would be produced in a perfectly competitive market where P = MC.

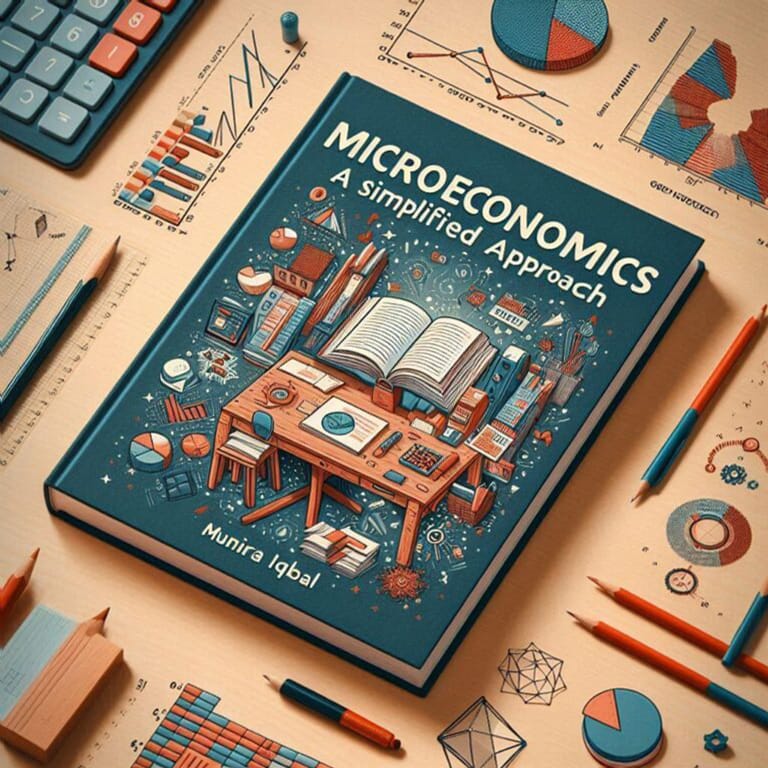

Numerical Example of Monopoly Inefficiency

The deadweight loss (DWL) due to monopoly inefficiency is 225. This represents the loss in total surplus (consumer surplus + producer surplus) that occurs because the monopolist produces less output and charges a higher price compared to a perfectly competitive market.

Summary

Monopolies are associated with both allocative and productive inefficiencies. Allocative inefficiency arises because monopolists set prices above marginal costs, leading to deadweight loss. Productive inefficiency occurs as monopolists may not produce at the lowest average cost due to a lack of competition. These inefficiencies highlight the social costs of monopoly power in an economy.

Intimidating Potential Competition with Predatory Pricing:

Predatory pricing is a strategy where a dominant firm sets prices below its costs to drive competitors out of the market or deter new entrants. Once the competition is weakened or eliminated, the firm can raise prices again to recoup its losses. This practice can be particularly effective in creating barriers to entry and maintaining monopoly power.

How Predatory Pricing Works

- Initial Low Pricing: The dominant firm sets prices below its average variable costs, which means it is selling at a loss.

- Competitor Response: Competitors, particularly smaller ones, cannot sustain the losses and either exits the market or is deterred from entering.

- Market Exit: Once competitors exit, the dominant firm increases prices to a higher level than before, often higher than the competitive level, to recover its losses.

World Around Us: Predatory Prices

Case Study: Walmart

- Background: Walmart, known for its aggressive pricing strategies, has been accused of predatory pricing practices.

- Scenario: In several instances, Walmart has entered local markets, set prices extremely low, often below its variable costs, to drive out smaller retailers.

- Outcome: Many small competitors could not sustain the losses and were forced to exit the market. Once Walmart dominated the local market, prices were gradually increased.

Implications and Regulation

Predatory pricing is often scrutinized by regulatory authorities as it can lead to anti-competitive behavior and consumer harm in the long run. Regulators like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the United States monitor such practices to prevent abuse of market power.

Graphical Representation of Predatory Prices:

The above diagram can help explain this concept within the context of a monopoly.

Figure 11.8 Predatory Pricing by Monopolists

- Initial Pricing (P1, Q1):

- The monopolist sets the initial price at P1 and produces quantity Q1, resulting in point E1 where AR intersects AC.

- At this point, the monopolist is covering costs and earning profits.

- Predatory Pricing Strategy:

- The monopolist lowers the price to P2 to increase output to Q2, represented by point E2 where AR2 intersects AC at a lower level.

- The price P2 might be below average cost (AC), indicating that the firm is incurring losses on each unit sold.

- The intention is to drive competitors out of the market by making it unsustainable for them to operate at such low prices.

- Outcome of Predatory Pricing:

- If competitors exit the market due to sustained losses, the monopolist then raises prices back to or above the original level (P1) to recoup the losses incurred during the predatory pricing period.

- Once competitors are eliminated, the monopolist can further increase prices, reduce output, and maximize profits without the threat of competition.

Explanation with an Example

Consider the case of a large retail chain that uses predatory pricing to eliminate smaller competitors:

- Initial Market Conditions:

- The large retailer sets prices at a profitable level (P1) with sufficient margins.

- Smaller retailers also operate at this price level, managing to cover their costs and make modest profits.

- Predatory Pricing Initiated:

- The large retailer significantly reduces prices to P2, below its average costs.

- Smaller retailers cannot sustain operations at these low prices and begin to incur losses.

- Competitor Exit:

- Over time, the smaller retailers are forced to exit the market as they cannot compete with the artificially low prices.

- The market sees a reduction in competition, leaving the large retailer as the dominant player.

- Post-Predatory Pricing:

- With reduced competition, the large retailer increases prices back to P1 or even higher, ensuring higher profit margins.

- The market becomes less competitive, leading to potential inefficiencies and higher prices for consumers in the long run.

Summary

Predatory pricing is a strategic tool used by dominant firms to eliminate competition and maintain market control. By understanding its mechanics and implications, policymakers and regulators can better protect competitive market structures and prevent monopolistic abuses.

Post-Monopoly Market Evolution

When monopolies find it difficult to sustain their dominance due to market saturation, several important shifts and developments can occur. Let’s explore these in detail:

1. Emergence of Oligopolies

As monopolies dissolve, often a few large firms dominate the market instead of just one, leading to an oligopoly. In an oligopolistic market, a small number of companies hold significant market shares, which can lead to strategic behavior such as price fixing, market sharing, and other forms of collusion.

Example:

The global smartphone market is an example of an oligopoly with key players like Apple, Samsung, Huawei, and Xiaomi. These companies dominate the market and often engage in competitive strategies like innovation races and marketing wars.

2. Increased Competition and Market Entry

With the fall of monopolistic control, new entrants find it easier to enter the market. Increased competition leads to more innovation, better customer service, and lower prices for consumers.

Example:

The breakup of AT&T in the 1980s led to the emergence of several new telecommunications companies, fostering a competitive environment that accelerated innovation and reduced prices.

3. Technological Advancements and Innovation

Freed from monopolistic constraints, markets often see a surge in technological advancements and innovation. Companies, new and old, invest heavily in R&D to gain a competitive edge.

Example:

After the breakup of the Bell System (AT&T), technological advancements in telecommunications and internet services surged, contributing to the rapid growth of the digital economy.

4. Diversification of Products and Services

Companies diversify their offerings to cater to varied consumer preferences, leading to a broader range of products and services in the market. This diversification can fulfill niche markets and cater to specific consumer needs.

Example:

Post the deregulation of airlines in the United States, companies like Southwest Airlines introduced low-cost carrier models, catering to budget-conscious travelers and significantly altering the aviation market.

5. Globalization and International Trade

As markets open up, globalization becomes a key factor. Companies expand their operations internationally, leading to increased global trade and competition.

Example:

The automobile industry saw increased international competition with Japanese car manufacturers like Toyota and Honda entering global markets, challenging American and European automakers.

6. Development of New Market Structures

New market structures such as monopolistic competition and perfect competition can emerge. In monopolistic competition, many firms compete, but each one sells a slightly differentiated product. In perfect competition, many firms sell identical products, and no single firm can influence the market price.

Example:

The fashion industry is an example of monopolistic competition where numerous brands offer differentiated products, catering to various styles and preferences.

Summary

The dissolution of monopolies and subsequent market saturation lead to a more dynamic and competitive market environment. This transition fosters innovation, diversity, and efficiency, benefiting consumers and the economy. Understanding these market evolutions helps policymakers and business leaders to create strategies that promote fair competition and sustainable growth.

Lessons for Policymakers

Policymakers can draw several lessons from these market dynamics:

- Promote Competition: Encourage policies that prevent monopolistic practices and promote fair competition.

- Support Innovation: Invest in and support R&D to foster technological advancements.

- Regulate Fairly: Implement regulations that prevent anti-competitive behavior without stifling innovation.

- Monitor Market Entry: Facilitate the entry of new firms to maintain a competitive market environment.

- Encourage Global Trade: Support globalization initiatives to increase international trade and competition.

These lessons are crucial for developing economic policies that balance market efficiency with consumer welfare and economic growth.

Monopoly through the Lens of Behavioral Economics

In a monopoly, a single firm dominates the market, setting prices without competition. Traditional economics assumes that monopolists act rationally to maximize profits. However, behavioral economics suggests that cognitive biases and psychological factors can influence decisions even in monopolistic markets.

Scenario: Pharmaceutical Monopoly

Consider a large pharmaceutical company with exclusive rights to produce a life-saving drug. As a monopolist, it sets prices much higher than marginal costs to maximize profits.

Cognitive Biases

- Status Quo Bias: The pharmaceutical company might maintain high prices due to inertia, even when new data suggests that lowering prices could increase overall revenue by expanding the market. The company might also resist changing its business model due to fear of losing its dominant market position.

- Anchoring Bias: When initially setting prices, the firm may anchor them to historical figures from other drugs, regardless of current market demand or societal needs. This bias could prevent the company from optimizing its pricing strategy.

Prospect Theory and Loss Aversion

- Loss Aversion: The monopolist may fear reducing prices, even if it could increase demand, due to the potential perceived loss of profit per unit. This behavior is explained by the firm’s disproportionate sensitivity to potential losses compared to gains.

- Framing Effect: If the company frames a price reduction as a loss in profit rather than an opportunity for market expansion, it might hesitate to adjust prices downward, despite potential long-term benefits.

World Around Us

A study of the monopolistic pricing of HIV drugs in the 2000s showed that companies were slow to reduce prices even in poorer countries. This behavior was partly driven by loss aversion and overconfidence in maintaining high profits. Eventually, external pressures and new competition forced price reductions, but only after significant public outcry and legal challenges. Prices dropped by 50%, leading to a 300% increase in sales globally, illustrating how behavioral biases initially hindered optimal decision-making.

Impact and Analysis

This case highlights that monopolists, driven by cognitive biases like loss aversion and anchoring, may fail to adjust prices optimally. Behavioral economics reveals why monopolists may stick to high prices longer than is rational, leading to inefficient market outcomes and potential welfare losses for consumers.

References

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk.

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness.

- HIV Drug Pricing Study, 2003.

By applying behavioral economics to the monopoly model, this case study emphasizes the importance of psychological insights in understanding market dynamics and the behavior of firms with market power.

Research Suggestions in Behavioral Economics

1. Monopolistic Price Setting and Cognitive Biases

Research how biases like anchoring and loss aversion affect price-setting behavior in monopolistic markets, particularly in industries like pharmaceuticals and technology.

2. Framing and Decision-Making in Monopoly

Investigate how the framing of potential gains and losses influences the strategic decisions of monopolists, particularly in pricing and product launches.

3. Behavioral Insights into Monopolistic Competition

Explore how monopolists react to potential threats of new entrants or substitute goods, particularly how overconfidence or loss aversion may delay adaptation or innovation.

4. Nudging Monopolistic Firms

Examine the impact of nudges or policy interventions that encourage monopolists to adopt socially beneficial pricing strategies, such as tiered pricing based on income levels or regions.

5. Long-Term Impact of Behavioral Interventions

Study the long-term effects of behavioral interventions on monopolistic markets, focusing on industries where pricing has significant societal impacts (e.g., healthcare, energy).

Critical Thinking

- How does the behavior of a monopolist differ from that of a perfectly competitive firm in terms of pricing and output decisions?

- In what ways does the presence of barriers to entry contribute to the inefficiencies observed in monopoly markets?

- Explain the concept of allocative inefficiency in the context of monopoly. How does it differ from productive inefficiency?

- How does the presence of a monopoly lead to a deadweight loss in the market? Use a diagram to illustrate your answer.

- What are the long-term effects of predatory pricing on market competition and consumer welfare?

- Can predatory pricing be beneficial for consumers in any way, even if only temporarily? Discuss with examples.

- What role do government regulations and antitrust laws play in preventing monopolistic behavior and promoting market competition?

- Analyze a real-world case where a government intervention successfully restricted monopolistic practices.

- Explain why the marginal revenue of a monopolist is always less than the price it charges for its product.

- How does a monopolist determine its profit-maximizing level of output? Use the MR=MC rule in your explanation.

- How might monopolies invest in innovation differently compared to firms in a perfectly competitive market?

- Discuss whether monopolies can ever lead to positive outcomes in terms of technological advancement and innovation.

One Comment