Understanding financial markets is essential for making informed economic and investment decisions. While the markets are generally efficient, being aware of their complexities, potential inefficiencies, and the impact of human behavior can help navigate them more effectively. By employing this knowledge, individuals, businesses, and policymakers can contribute to a more stable and prosperous financial environment.

Demand and Supply in Financial Markets

- Demanders in Financial Markets: Borrowers: Individuals and businesses that need funds. For example, a company may issue bonds to finance a new project.

- Suppliers in Financial Markets: Lenders/Investors: Those who have extra funds and want to invest them. For instance, people buy bonds to earn interest.

- Interest Rates: Interest rates are the cost of borrowing money. High-interest rates can reduce borrowing because it’s more expensive to take loans, while low rates can encourage borrowing.

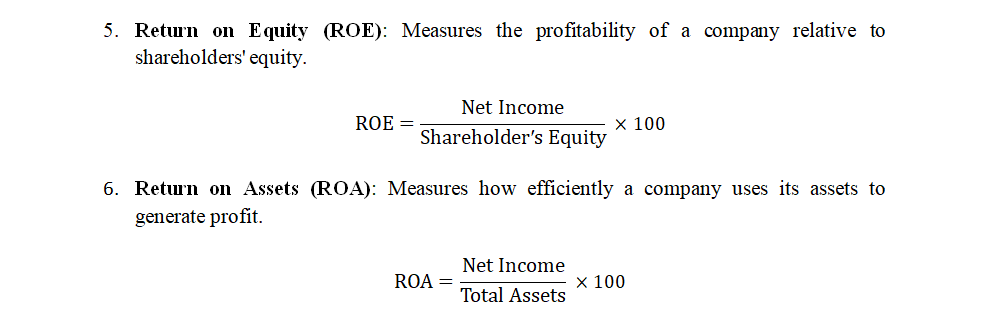

The Mechanism of Financial Market

In any market, the price is what suppliers receive and what demanders pay. In financial markets, savers supply financial capital and expect to earn a return. Borrowers demand financial capital and expect to pay a return. This return can take different forms depending on the type of investment.

Interest Rates as Rates of Return

The simplest example of a return is the interest rate. For instance, when you deposit money in a bank savings account, you earn interest on your deposit. The bank disburses your interest as a percentage of your deposit, which is the interest rate. Similarly, if you borrow money to buy a car or a computer, you will pay interest on the loan.

Interest Rates

Definition: The percentage of the principal amount charged by the lender to the borrower for the use of assets. It is typically expressed on an annual basis (annual percentage rate, APR).

Types of Interest Rates:

1. Nominal Interest Rate: The stated rate on a loan or investment, not adjusted for inflation.

2. Real Interest Rate: The nominal interest rate adjusted for inflation. It represents the true cost of borrowing. It can be expressed as

Real Interest Rate = Nominal Interest Rate – Inflation Rate

3. Fixed Interest Rate: The rate remains constant throughout the life of the loan or investment.

4. Variable Interest Rate: The rate can change over time, typically based on an underlying benchmark rate like LIBOR or the Federal Funds Rate.

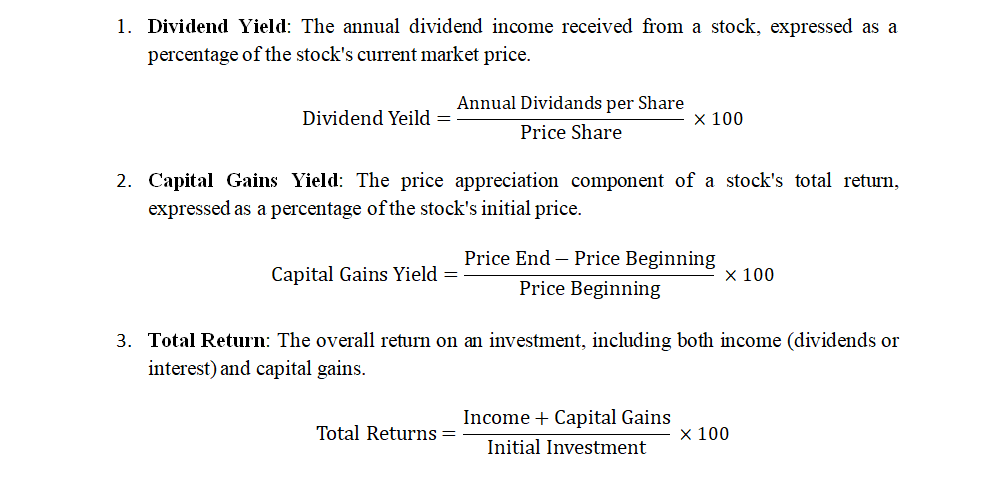

Rates of Return

Rates of return measure the gain or loss on an investment over a specific period, expressed as a percentage of the investment’s initial cost.

Definition: The percentage change in the value of an investment over a given period of time.

Types of Rates of Return:

Different Forms of Rates of Return

- Yield to Maturity (YTM): The total return anticipated on a bond if it is held until it matures. It includes interest payments and any gain or loss if the bond is purchased at a price other than its par value.

The calculation involves solving for YTM in the bond pricing formula, which are complex and usually done using financial calculators or spreadsheet software.

Numerical Example

Consider an investor who purchases 100 shares of a company at $50 per share. Over the year, the stock price increases to $55 per share, and the company pays a $2 dividend per share.

Credit Cards: An Example of Financial Market

Let’s look at the market for borrowing money with credit cards. In 2021, almost 200 million Americans had credit cards. Credit cards let you borrow money from the card issuer and pay it with interest. Many cards offer a grace period where you can repay without interest. Typical credit card interest rates range from 12% to 18% per year. By May 2021, Americans had about $807 billion in outstanding credit card debt. Over 45% of American families carried some credit card debt. Let’s say the average annual interest rate for credit card borrowing is 15%. This means Americans pay tens of billions of dollars each year in credit card interest, plus fees for late payments and other charges.

Demand and Supply in the Credit Card Market

Here’s how demand and supply for credit card borrowing work.

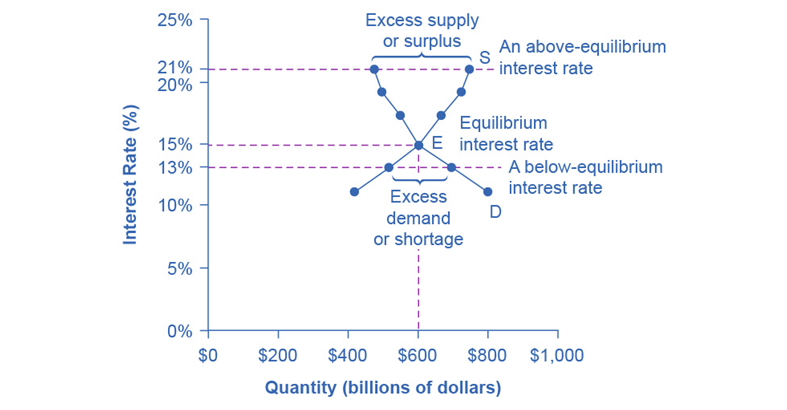

Figure 5.1: Demand and Supply for Borrowing Money with Credit Cards

- Demand: The horizontal axis shows the quantity of money loaned or borrowed.

- Supply: The vertical axis shows the rate of return, which for credit card borrowing is the interest rate.

The graph in Figure 5.1 shows demand and supply for credit card borrowing. The horizontal axis shows the quantity of money loaned or borrowed. The vertical axis shows the rate of return, which for credit card borrowing is the interest rate. Table shows the quantity of financial capital consumers’ demand at various interest rates and the quantity that credit card firms (often banks) are willing to supply.

| Interest Rate (%) | Quantity of Financial Capital Demanded (Borrowing) ($ billions) | Quantity of Financial Capital Supplied (Lending) ($ billions) |

| 11 | $800 | $420 |

| 13 | $700 | $510 |

| 15 | $600 | $600 |

| 17 | $550 | $660 |

| 19 | $500 | $720 |

| 21 | $480 | $750 |

Table 5.1: Demand and Supply for Borrowing Money with Credit Cards

Laws of Demand and Supply in the Financial Market

The laws of demand and supply apply in financial markets.

- Law of Demand: A higher rate of return (or higher interest rate) decreases the quantity demanded. As interest rates rise, consumers borrow less.

- Law of Supply: A higher price increases the quantity supplied. Thus, as the interest rate on credit card borrowing rises, more firms will issue credit cards and encourage their use.

Equilibrium in Financial Markets

Equilibrium in financial markets occurs when the quantity of financial capital supplied equals the quantity of financial capital demanded. At this point, the interest rate, which acts as the “price” in these markets, balances the supply and demand.

Key Points of Equilibrium:

- Equal Supply and Demand: The amount of money that savers (suppliers) are willing to lend is exactly equal to the amount that borrowers (demanders) want to borrow.

- Stable Interest Rate: The interest rate at equilibrium is stable because there is no pressure to change. If the rate were higher, there would be a surplus of capital. If it were lower, there would be a shortage.

- Market Balance: At equilibrium, financial markets are in balance. Lenders get the return they expect, and borrowers can obtain the funds they need without paying excessively high rates.

Example:

Consider the market for credit cards. If the equilibrium interest rate is 15%, this means:

- Suppliers (Banks): Banks are willing to lend a total of $600 billion at this rate.

- Demanders (Consumers): Consumers are willing to borrow $600 billion at this rate.

At this interest rate, the market is in balance, with no excess supply or demand. If the interest rate rises above 15%, fewer consumers will borrow, leading to a surplus of funds. If the rate falls below 15%, more consumers will want to borrow, leading to a shortage of funds.

Shifting Interest Rates and Market Effects

Above Equilibrium: If the interest rate is above equilibrium, there will be excess supply or a surplus of financial capital. For example, at 21%, the quantity of funds supplied rises to $750 billion, but the quantity demanded falls to $480 billion.

Below Equilibrium: If the interest rate is below equilibrium, there will be excess demand or a shortage of funds. At 13%, the quantity of funds demanded rises to $700 billion, but the quantity supplied falls to $510 billion.

Summary

In summary, equilibrium in financial markets ensures that the quantity of capital supplied by savers matches the quantity demanded by borrowers, creating a stable and balanced market environment.

Decisions in Financial Markets

Saving Decisions

People must decide how much of their income to save and where to invest it. This process involves choosing between immediate consumption and saving for future needs.

- Inter-temporal Decision Making: Unlike everyday purchases, saving involves planning across time, such as for retirement when income decreases.

- Influence of Social Security: Programs like Social Security can reduce the amount people save, shifting the supply of financial capital downward.

Borrowing Decisions

Individuals and businesses borrow to finance current needs with the expectation of repaying in the future.

- Student Loans and Investments: College students often borrow for education expenses, anticipating higher future income.

- Business Investments: Companies borrow to fund long-term projects, with confidence in future returns influencing their borrowing decisions.

Shifting Demand for Financial Capital

Economic conditions and confidence affect how much capital consumers and businesses demand.

- Technology Boom Example: During the late 1990s tech boom, businesses were confident in high returns from investments, increasing demand for financial capital.

- Impact of Economic Crises: During the 2008 recession, reduced confidence led to lower demand for financial capital.

Factors Influencing Investment Choices

Investors consider returns and risks when choosing where to allocate their savings.

- Rate of Return vs. Risk: Investments offering higher returns attract more capital, while increased risk can deter investment.

- Shifting Supply Curves: If one investment becomes riskier or less profitable, capital shifts to other investments offering better returns.

In summary, decisions about saving and borrowing in financial markets are influenced by individuals’ and businesses’ expectations of future income and economic conditions. Shifts in demand and supply for financial capital reflect these dynamics, impacting investment choices and market stability.

Financial Market Efficiency

Market efficiency is a critical concept in understanding how financial markets function. It suggests that financial markets effectively and efficiently allocate resources by accurately reflecting all available information in asset prices. This means that the prices of stocks, bonds, and other securities are always fair and represent the true value of these assets based on the information available at any given time.

Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is the theory underlying market efficiency. It hypothesizes that it is impossible to consistently achieve higher returns than the average market returns on a risk-adjusted basis, given that all available information is already reflected in asset prices. There are three forms of EMH:

Weak Form Efficiency:

- Definition: Suggests that all past trading information, such as stock prices and volume, is fully reflected in current prices.

- Implication: Technical analysis, which involves analyzing past price movements and patterns, is ineffective in predicting future price movements and achieving above-average returns.

Semi-Strong Form Efficiency:

- Definition: Asserts that all publicly available information, including financial statements, news, and economic data, is already incorporated into stock prices.

- Implication: Fundamental analysis, which involves evaluating a company’s financial health and performance, cannot consistently yield higher returns than the market average because all available information is already reflected in stock prices.

Strong Form Efficiency:

- Definition: Claims that all information, both public and private (insider information), is fully reflected in stock prices.

- Implication: Not even insider trading can result in consistently higher returns because even non-public information is already accounted for in asset prices.

Key Concepts Related to Market Efficiency

Information Dissemination and Impact

- Speed of Adjustment:

Market efficiency relies on the speed at which new information is incorporated into asset prices. In highly efficient markets, prices adjust almost instantaneously to new information, minimizing opportunities for investors to exploit temporary mispricing.

- Public and Private Information:

Efficient markets incorporate both public information (readily available to all investors) and private information (known only to insiders). The strong form of market efficiency argues that even insider information is reflected in stock prices, making it impossible to gain an advantage.

Behavioral Finance

- Market Anomalies:

Despite the theory of market efficiency, certain market irregularities challenge its validity. For instance, the January effect (where stock prices tend to rise in January) and momentum (where stocks that have performed well in the past continue to do well in the short term) suggest that some patterns and trends can be exploited.

- Investor Psychology:

Behavioral finance examines how psychological factors and biases affect investor behavior and market outcomes. Emotions such as fear and greed can lead to irrational decisions, causing temporary mispricing in the market. This perspective argues that markets are not always perfectly efficient due to human behavior.

World Around Us: Market efficiency

Dot-Com Bubble (Late 1990s to Early 2000s):

During the dot-com bubble, many internet-based companies saw their stock prices soar despite having no substantial revenues or profits. Investors were overly optimistic about the potential of these companies, leading to inflated prices. When reality set in, and many of these companies failed to deliver on their promises, the bubble burst, and stock prices plummeted, highlighting how market inefficiencies can occur due to speculative behavior.

Global Impact: The dot-com bubble primarily affected the United States but had global repercussions. Major stock exchanges such as the NASDAQ saw unprecedented rises and subsequent crashes.

Tech-Heavy Regions: Areas with a high concentration of technology companies, such as Silicon Valley in California, were particularly impacted. The bubble led to massive layoffs, bankruptcies, and a significant reduction in venture capital investments in the tech sector.

Great Recession (2007-2009):

The housing market crash and subsequent financial crisis demonstrated inefficiencies in both housing and financial markets. Poor risk assessment, excessive leverage, and the widespread belief that housing prices would continue to rise led to a massive bubble. When the bubble burst, it caused a significant economic downturn. This event emphasized the importance of proper information dissemination and risk management in maintaining market efficiency.

United States: The epicenter of the Great Recession was the United States, where the collapse of the housing market and the failure of major financial institutions like Lehman Brothers triggered the crisis.

Global Impact: The financial crisis quickly spread worldwide, affecting economies in Europe, Asia, and other regions. Countries with significant financial and trade links to the United States, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and China experienced severe economic downturns.

Major Financial Centers: Financial hubs such as New York City, London, and Frankfurt were heavily impacted due to their roles in the global financial system. The crisis led to significant losses for banks, insurance companies, and investors in these cities.

GameStop Short Squeeze (2021):

The GameStop short squeeze, driven by retail investors on platforms like Reddit, led to dramatic price increases in the stock. This phenomenon was partly due to coordinated buying efforts and the exploitation of short positions held by institutional investors. It illustrated how market dynamics can be influenced by collective behavior and social media, challenging traditional notions of market efficiency.

United States: The primary location of the GameStop short squeeze was the United States, where GameStop, a video game retail company, is based and publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).

Online Platforms: The coordination of the short squeeze occurred largely on social media platforms, particularly Reddit, within the “WallStreetBets” community. This online activity played a central role in mobilizing retail investors.

Global Financial Markets: The impact of the short squeeze was felt globally, as the rapid price movements in GameStop’s stock affected international hedge funds, trade platforms, and investors worldwide. Major financial centers like New York and London experienced significant market instability due to the event.

Evaluating Market Efficiency

Empirical Tests:

Researchers use various statistical methods to test market efficiency. For example, they analyze whether stock prices follow a random walk, meaning future price changes are independent of past changes. Studies often examine stock returns after public announcements to see if prices adjust quickly and correctly. (We will discuss the random walk model in next section).

Market Structure and Regulation:

The structure of financial markets and the level of regulation can affect efficiency. Well-regulated markets with transparent processes and robust legal frameworks are more likely efficient. Conversely, markets with significant barriers to information flow or poor regulatory oversight may exhibit inefficiencies.

Technology and Information Dissemination:

Advances in technology and information dissemination have enhanced market efficiency. High-frequency trading, algorithmic trading and the widespread availability of financial data have reduced the time it takes for new information to be reflected in prices. However, these technologies also raise concerns about market manipulation and fairness.

Summary

Understanding market efficiency is crucial for investors, policymakers, and financial professionals. It helps in making informed investment decisions, designing effective regulatory frameworks, and recognizing the limitations of financial markets. While the Efficient Market Hypothesis provides a robust framework, real-world events and behavioral factors highlight that markets are not always perfectly efficient. By acknowledging these complexities, we can better navigate the financial landscape and strive for more efficient and fair markets.

Getting Rich is Difficult for Everyone

Getting rich through investing in stocks may seem straightforward at first glance. The idea is to identify companies hovering for growth and high profitability, or those that will become popular among investors. Investing in these companies can potentially lead to high dividends or an increase in stock prices, allowing investors to multiply their money.

However, this path to riches is not as easy as it sounds. Here’s why:

Problems with Picking Stocks:

Uncertainty: Predicting future stock prices is inherently uncertain. Stock prices can be influenced by numerous factors such as market sentiment, economic conditions, and company-specific developments.

Risk: Investing in individual stocks carries a high level of risk. If the chosen company underperforms or faces challenges, investors may experience significant losses.

Market Efficiency: The efficient market hypothesis suggests that stock prices already reflect all available information. This makes it difficult for investors to consistently beat the market through stock picking alone.

A More Reliable Method:

Diversification: Instead of trying to pick individual stocks, a more reliable approach is diversifying investments across different asset classes (stocks, bonds, real estate, etc.) and geographic regions. Diversification helps spread risk and can provide more stable returns over the long term.

Passive Investing: Investing in index funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that track broad market indices can offer diversification benefits. These funds typically have lower costs and provide exposure to a wide range of stocks without the need for active stock picking.

Long-Term Perspective: Adopting a long-term investment horizon allows investors to ride out market fluctuations and benefit from compounding returns.

Summary

In summary, while picking individual stocks based on growth potential may seem attractive. It involves significant risks and uncertainties. A more cautious approach to accumulating wealth involves diversification and adopting a long-term investment strategy. This approach may be less glamorous but tends to be more reliable and conducive to sustainable wealth accumulation over time.

Getting Rich in Underdeveloped and Corrupt Countries

Additional Challenges for Investors

Investors in countries with high corruption levels and weak enforcement of financial regulations face unique difficulties, which often make traditional investment strategies less reliable:

- Lack of Investor Protection: Limited enforcement of financial regulations and the risk of corruption in financial markets reduce confidence in the system.

- Currency Instability: Local currencies’ frequent devaluation against major currencies adds currency risk, which can erode the value of investments.

- Market Transparency: Insufficient access to reliable financial data makes it challenging to analyze company performance accurately.

Additinal Strategies for Investors

- Focus on Sectors with Stability

Some sectors, such as consumer goods, telecommunications, and utilities, tend to remain more stable. They often have strong demand, making them potentially safer for investments. - Invest in Government Bonds

Government-backed bonds or certificates, like Pakistan Investment Bonds (PIBs) or National Savings Schemes (NSS), offer relatively stable returns and are less risky than stocks. - Use Gold as a Hedge

Gold holds significant value in Pakistan as a stable asset. It often increases in value during economic uncertainty, providing a hedge against inflation and currency devaluation. - Consider Real Estate for Long-Term Growth

Real estate is a common investment choice in Pakistan due to its long-term growth potential. Land and property values tend to be appreciated, especially in urban areas. - Prioritize Long-Term Over Short-Term Gains

Given the volatile market and economic situation, a long-term investment approach, as seen in developed economies, can help reduce the impact of short-term market fluctuations.

Summary: Adapting to the Environment

While investing in stocks can be a path to wealth, investors in countries with economic challenges need to adapt their strategies. By focusing on stable sectors, safer assets like government bonds, and longer investment horizons, they can manage risks better. Also, including physical assets like gold or real estate can offer additional security in uncertain economic environments.

Random Walk Theory

The Random Walk Theory suggests that stock market prices evolve randomly and independently of past prices. According to this theory, future price movements cannot be predicted based on historical patterns or trends.

Explanation:

Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH): The Random Walk Theory is closely related to the EMH, which suggests that financial markets efficiently incorporate all available information into stock prices.

Implications: Investors cannot consistently outperform the market through technical analysis (analyzing past price movements) because stock prices already reflect all available information.

Example:

Suppose a stock’s price movements follow a random pattern, where each day’s price change is independent of the previous day. An investor relying solely on historical price trends to predict future movements would find it challenging to consistently make accurate predictions.

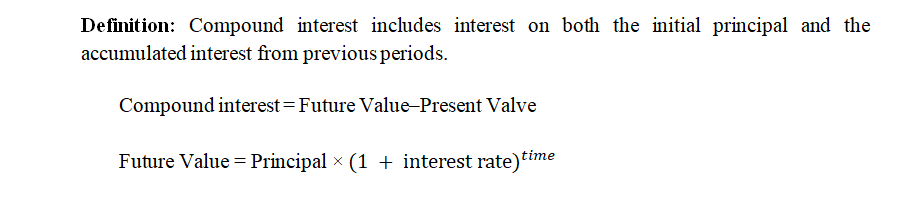

Calculating Simple and Compound Interest

Simple Interest:

Definition: Simple interest is calculated by multiplying the initial principal amount invested or loaned.

Simple Interest Rate= P x r x t

Where

- P is the principal amount,

- r is the annual interest rate (decimal form), and

- t is the time period in years.

Compound Interest:

Definition: Compound interest includes interest on both the initial principal and the accumulated interest from previous periods.

Evaluating How Capital Markets Transform Financial Capital

Capital markets facilitate the buying and selling of financial securities such as stocks, bonds, and derivatives. They enable individuals and institutions to invest capital and raise funds for business expansion, infrastructure projects, and other economic activities.

Transformation Process:

Capital Allocation: Investors provide funds (financial capital) to businesses and governments seeking capital for projects or operations.

Efficiency: Capital markets efficiently match savers (suppliers of capital) with borrowers (demanders of capital) through mechanisms like stock exchanges, bond markets, and venture capital funds.

Impact: By enabling efficient capital allocation, capital markets support economic growth, job creation, and innovation.

Example:

Initial Stage: A technology startup raises $10 million from venture capitalists through an initial public offering (IPO) on a stock exchange.

Transformation: The startup uses these funds to develop new products, expand operations, and hire additional employees.

Result: As the startup grows, its increased productivity and profitability contribute to economic growth and potentially higher returns for investors.

Summary

Understanding concepts like the Random Walk Theory, simple and compound interest calculations, and the role of capital markets in transforming financial capital is essential for making informed financial decisions and achieving long-term wealth accumulation. These concepts illustrate how financial markets operate and their impact on individuals, businesses, and economies.

Points to Remember

Interest Rates and Their Impact

How Interest Rates Affect Supply and Demand

Higher interest rates increase the cost of borrowing, leading to lower demand for loans. Conversely, lower interest rates make borrowing cheaper, increasing demand for loans.

Economic Effects of U.S. Debt

High U.S. debt can lead to higher interest rates, affecting domestic financial markets. For instance, if the U.S. government borrows heavily, it might drive up interest rates, making loans more expensive for businesses and individuals.

Role of Price Controls

Price Ceilings and Usury Laws

Price ceilings and usury laws are regulatory measures aimed at protecting consumers in various financial transactions. They have been implemented in several jurisdictions around the world, including certain U.S. states, to ensure fairness and prevent exploitation in markets like payday loans. Here’s a brief overview of their feasibility and impact:

Price Ceilings:

Definition: Price ceilings are government-imposed limits on how high prices can be charged for certain goods or services. They are intended to prevent sellers from setting excessively high prices that could harm consumers, especially during times of economic stress or in essential markets.

Feasibility: Implementing price ceilings can be feasible in specific circumstances where there is a perceived market failure or when consumer protection is a priority. For example, during natural disasters or emergencies, price ceilings on essential items like food and water can ensure affordability for all consumers.

Impact: While price ceilings aim to protect consumers by keeping prices affordable, they can also lead to unintended consequences. These may include shortages of the regulated goods or services, reduced quality due to lack of incentive for producers, and the emergence of black markets where prices are unregulated.

Usury Laws:

Definition: Usury laws are regulations that limit the maximum interest rates that lenders can charge on loans. These laws are intended to prevent predatory lending practices and protect borrowers from excessive financial burden.

Feasibility: Usury laws are feasible and have been implemented in various forms across different regions globally. They typically target high-cost credit products like payday loans, where interest rates can be exceptionally high, trapping borrowers in cycles of debt.

Impact: Usury laws can effectively protect vulnerable borrowers by capping interest rates and ensuring that loan terms are fair and transparent. However, they may also reduce access to credit for higher-risk borrowers who may not qualify under stricter lending criteria.

World Around Us: Price Ceiling and Usury Laws

- United States: Some U.S. states have implemented usury laws to cap interest rates on payday loans. For instance, states like New York and California have set maximum annual percentage rates (APRs) for payday loans to protect consumers from overpriced interest charges.

- Europe: Countries within the European Union have varying usury laws, with regulations on consumer credit to prevent lenders from exploiting borrowers with excessive interest rates.

- Developing Countries: Many developing countries also have usury laws or similar regulations aimed at preventing predatory lending practices and protecting low-income borrowers.

Summary

While price ceilings and usury laws are feasible regulatory tools that aim to protect consumers from exploitation. Their impact can vary depending on implementation and market conditions. They play a crucial role in balancing consumer protection with market efficiency, but policymakers must carefully consider their potential unintended consequences when designing and enforcing these regulations.

Analyzing Prices and Quantities in Financial Market: Applying Demand and Supply Models

These models help us understand how prices and quantities are determined in markets. For instance, if there is a high demand for housing but limited supply, prices will rise.

Effects of Price Controls

Price controls can lead to shortages or surpluses. For example, rent control can make housing more affordable but may reduce the number of available rental properties as landlords might not find it profitable.

World Around Us: Effects of Price Controls

Case Study 1: The European Sovereign Debt Crisis (2009-2012)

Background: The European Sovereign Debt Crisis was a period during which several European countries faced significant financial turmoil due to high levels of sovereign debt. The crisis particularly affected countries in the Eurozone, including Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Italy.

Some Facts and Figures:

High Sovereign Debt: Countries like Greece had extremely high levels of public debt relative to their GDP. For instance, Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio was around 146% in 2010.

Bond Yields: During the crisis, the yields on government bonds for these countries soared. For example, Greek 10-year bond yields peaked at around 30% in early 2012.

Bailouts and Austerity: The European Union and the International Monetary Fund provided bailout packages totaling over €240 billion to Greece alone, conditional with the implementation of strict austerity measures.

Analysis Using Demand and Supply Models:

Demand for Bonds: In a stable market, government bonds are seen as low-risk investments, leading to high demand and relatively low yields. However, as concerns over the solvency of these countries grew, the demand for their bonds dropped, driving up yields.

Supply of Bonds: To finance their deficits, these countries continued to issue bonds. The increased supply, coupled with decreased demand, resulted in significantly higher borrowing costs.

Market Effects: The high yields on bonds reflected the market’s perception of increased risk, leading to a vicious cycle where higher borrowing costs made it even harder for these countries to service their debts, further worsening the crisis.

Impact of Price Controls:

Interest Rate Manipulation: The European Central Bank (ECB) intervened by buying sovereign bonds from the affected countries, a form of price control aimed at lowering yields and stabilizing the market.

Quantitative Easing: The ECB’s actions were akin to implementing a price ceiling on bond yields. While this helped to bring down the cost of borrowing and provided temporary relief, it also led to debates on the long-term impacts of such interventions on market efficiency and moral hazard.

Global Impact:

Economic Contraction: The austerity measures required by bailout conditions led to significant economic contraction in the affected countries. For instance, Greece GDP contracted by about 25% from 2008 to 2013.

Unemployment: Unemployment rates soared, with Greece and Spain experiencing rates above 25% during the peak of the crisis.

Political Instability: The economic hardship and austerity measures led to political instability and social unrest in many countries, with frequent protests and the rise of anti-austerity political parties.

Case Study 2: The Impact of Interest Rate Controls in India

Background: India has implemented various interest rate controls over the years to manage inflation and promote economic growth.

Facts and Figures:

- Interest Rate Caps: The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has historically set caps on interest rates for certain types of loans to make borrowing more affordable.

- Credit Supply: When interest rate caps are set too low, banks may reduce the supply of credit, leading to a credit crunch.

- Economic Impact: A study by the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy found that interest rate caps can lead to reduced investment and slower economic growth.

Analysis: Interest rate controls can lead to a reduced supply of credit, affecting overall economic activity. This case illustrates how price controls in financial markets can have broader economic implications.

Case Study 3: Government Intervention in the Forex Market in China

Background: China’s government has historically intervened in the foreign exchange (forex) market to control the value of the Yuan.

Facts and Figures:

Exchange Rate Peg: The Chinese government has pegged the Yuan to the U.S. dollar at various points to maintain a stable exchange rate.

Forex Reserves: To maintain the peg, China has cultivated significant foreign exchange reserves, reaching over $3 trillion in 2021.

Market Effects: The artificial control of the Yuan’s value can lead to trade imbalances and affect global financial markets. A report by the Peterson Institute for International Economics found that currency manipulation can lead to increased instability in global trade and investment.

Analysis:

Government intervention in the forex market can distort supply and demand dynamics, leading to broader market inefficiencies. This case demonstrates how price controls can affect not just domestic markets but also global financial stability.

Summary

Analyzing prices and quantities in financial markets using demand and supply models provides valuable insights into market dynamics. Price controls, while often well-intentioned, can lead to various unintended consequences such as shortages, reduced supply, and market distortions. These case studies demonstrate the importance of carefully considering the potential impacts of price regulations on both consumers and suppliers in the financial markets.

Early-Stage Financial Capital

Now we will discuss an essential aspect of financial markets: Early-Stage Financial Capital. This topic is crucial for understanding how new businesses and startups secure the funding they need to grow and succeed.

Definition of Early-Stage Financial Capital

Early-Stage Financial Capital refers to the funds needed by startups and new businesses during the initial phases of their development. This capital is critical for covering initial costs, such as product development, marketing, hiring, and operational expenses.

Importance of Early-Stage Financial Capital

Starting Operations: Without initial funding, a new business cannot start its operations.

Product Development: Early-stage capital is often used for developing and testing new products or services.

Market Entry: Funds are needed to enter the market, create awareness, and attract customers.

Hiring Talent: Recruiting skilled employees requires financial resources, especially for key positions.

Sustainability: Ensuring the business can survive until it becomes profitable.

Sources of Early-Stage Financial Capital

Personal Savings and Family/Friends

Personal Savings: Entrepreneurs often use their own savings to fund their business initially. This is the most common source of early-stage capital.

Family and Friends: Many startups receive financial support from family members and friends who believe in the business idea.

Example: In Pakistan, many small businesses start with funds from personal savings or loans from family members. For instance, a local bakery might be funded by the owner’s savings and contributions from relatives.

Angel Investors

Definition: Angel investors are wealthy individuals who provide capital to startups in exchange for ownership equity or convertible debt.

Role: They often invest in early-stage businesses with high growth potential and provide mentorship and industry connections.

Example: In India, angel investors have played a significant role in the success of startups like Ola and Flipkart, providing them with the necessary early-stage funding and guidance.

Venture Capital

Definition: Venture capital (VC) firms invest in startups with high growth potential in exchange for equity. They typically invest larger amounts than angel investors.

Stages of VC Investment: Venture capital funding can be divided into several stages, such as seed stage, early stage, and late stage.

Example: In China, venture capital has been a significant source of funding for tech startups like Alibaba and Tencent, helping them scale rapidly and become industry leaders.

Crowd-funding

Definition: Crowd funding involves raising small amounts of money from a large number of people, typically via online platforms.

Types: Reward-based crowd funding (backers receive a product or service) and equity crowd funding (backers receive equity in the company).

Example: In Bangladesh, startups like Pathao, a ride-sharing company, have successfully used crowd-funding platforms to raise early-stage capital and expand their operations.

Government Grants and Subsidies

Definition: Some governments provide grants, subsidies, and low-interest loans to support new businesses and stimulate economic growth.

Criteria: These funds are often awarded based on specific criteria, such as innovation, job creation, and industry sector.

Example: In South Korea, the government offers grants and subsidies to tech startups, encouraging innovation and helping them compete in global markets.

Challenges in Securing Early-Stage Financial Capital

High Risk: Early-stage businesses are risky investments, as they often lack a proven track record and face uncertainty.

Valuation Difficulties: Determining the value of a startup can be challenging, making it harder to negotiate investment terms.

Limited Access: Not all entrepreneurs have access to networks of angel investors or venture capital firms.

Strategies for Attracting Early-Stage Financial Capital

Strong Business Plan: A well-crafted business plan that outlines the business model, market opportunity, and growth strategy.

Prototypes and MVPs: Developing a prototype or minimum viable product (MVP) to demonstrate the business concept and potential.

Networking: Building relationships with potential investors, attending industry events, and leveraging professional networks.

Pitching Skills: Effectively communicating the business idea, potential market, and financial projections to investors.

Summary

Early-Stage Financial Capital is vital for the growth and success of new businesses. Understanding the various sources of funding and the challenges involved can help entrepreneurs secure the necessary resources to turn their ideas into reality. By offering personal savings, angel investors, venture capital, crowd-funding, and government support, startups can navigate the early stages and pave the way for future success.

Profits as a Source of Financial Capital

Now we will discuss how profits can be a vital source of financial capital for businesses. Understanding how profits contribute to financial growth is crucial for both new and established companies. We will explore the role of profits, how they can be reinvested, and the benefits and challenges associated with using profits as financial capital.

Profits:

Profits are the financial gains a company makes after deducting all its expenses from its total revenue. It is the difference between what the company earns and what it spends.

Importance of Profits as Financial Capital

Self-Sufficiency: Using profits as financial capital allows a business to fund its operations and growth without relying on external sources.

Control and Independence: Reinvesting profits ensures that the business owners retain control over the company, avoiding the need to share decision-making power with external investors.

Sustainability: A profitable business can sustain itself and grow organically, ensuring long-term stability.

How Profits are Used as Financial Capital

Reinvestment in Business Operations

Expansion: Profits can be reinvested to expand the business, open new locations, or enter new markets.

Product Development: Funds can be used to develop new products or improve existing ones, keeping the company competitive.

Marketing: Investing in marketing can help attract new customers and increase sales.

Example: In India, a small textile business may use its profits to purchase new machinery, allowing it to produce higher quality fabrics and expand its product line.

Debt Repayment

Reducing Liabilities: Utilizing profits to pay off debt reduces the financial liabilities and interest expenses of the company.

Improving Creditworthiness: A lower debt level can improve the company’s credit rating, making it easier to secure loans in the future.

Example: A Pakistani manufacturing company might use its profits to pay off a loan taken for factory expansion, thus reducing interest payments and improving its balance sheet.

Research and Development (R&D)

Innovation: Investing profits in R&D can lead to innovative products and processes, giving the company a competitive edge.

Long-Term Growth: Continuous innovation ensures the company remains relevant and can adapt to market changes.

Example: In South Korea, tech companies like Samsung reinvest a significant portion of their profits into R&D, driving technological advancements and maintaining market leadership.

Employee Development and Welfare

Training Programs: Profits can be used to provide training and development programs for employees, enhancing their skills and productivity.

Employee Benefits: Offering better benefits and incentives can improve employee satisfaction and retention.

Example: A Bangladeshi garment factory may use its profits to offer better wages and working conditions to its workers, improving overall productivity and reducing turnover.

Benefits of Using Profits as Financial Capital

No Debt: Funding growth through profits avoids borrowing, reducing financial risk.

No Equity Dilution: Using profits prevents the dilution of ownership, as there is no need to issue additional shares.

Flexibility: Profits provide a flexible source of capital that can be used for various purposes as needed.

Challenges of Using Profits as Financial Capital

Limited Availability: Not all businesses generate sufficient profits to fund significant growth or large projects.

Opportunity Cost: Reinvesting profits may mean less money available for other uses, such as dividends to shareholders.

Economic Downturns: During economic downturns or recessions, profits may decrease, limiting the available capital for reinvestment.

World Around Us: Profits as Financial Capital

Case Study 1: Apple Inc.

Background: Apple has a history of reinvesting its profits into R&D, leading to continuous innovation and the development of new products like the iPhone and iPad.

Impact: This strategy has helped Apple maintain its position as a market leader and consistently grow its revenue and profits.

Case Study 2: Tata Group (India)

Background: Tata Group, one of India’s largest multinational company, reinvests its profits into various business ventures, from steel manufacturing to software services.

Impact: This diversified reinvestment strategy has enabled Tata to grow sustainably and contribute significantly to India’s economy.

Case Study 3: Huawei (China)

Background: Huawei reinvests a large portion of its profits into R&D, focusing on telecommunications technology and innovation.

Impact: This has allowed Huawei to become a global leader in 5G technology and expand its market presence worldwide.

Summary

Profits are a crucial source of financial capital for businesses, offering a self-sufficient and flexible means of funding growth and innovation. By reinvesting profits, companies can expand, reduce debt, innovate, and improve employee welfare. However, it is essential to balance the use of profits with other financial needs and opportunities to ensure long-term success and sustainability.

Borrowing: Banks and Bonds

We will discuss two essential sources of financial capital for businesses: borrowing from banks and issuing bonds. Both methods allow companies to raise the funds they need for various purposes, such as expansion, research, and development. Understanding these financing options will help you make informed decisions in your future endeavors.

Borrowing from Banks

Loan Agreements: When a business borrows money from a bank, it enters into a loan agreement that specifies the amount borrowed, interest rate, repayment schedule, and any security required.

Interest Rates: The interest rate is the cost of borrowing the money, expressed as a percentage of the loan amount. It can be fixed or variable.

Repayment: The business must repay the loan amount, plus interest, over a specified period, usually in monthly installments.

Example: A small business in Pakistan might borrow a loan from a local bank to purchase new machinery. The bank charges a 10% annual interest rate, and the business agrees to repay the loan over five years.

Advantages of Bank Loans

Accessibility: Bank loans are relatively easy to obtain for businesses with good credit histories and guarantees.

Fixed Repayment Schedule: Businesses know exactly how much they need to repay each month, helping with budgeting and financial planning.

No Equity Dilution: Borrowing from banks requires no ownership or control of the business.

Disadvantages of Bank Loans

Interest Costs: The cost of borrowing can be high, especially for businesses with less favorable credit terms.

Collateral Requirements: Banks often require collateral, which can be a risk if the business cannot repay the loan.

Creditworthiness: Businesses with poor credit histories may struggle to obtain loans or face higher interest rates.

Issuing Bonds

Definition: Bonds are debt securities issued by companies or governments to raise capital. When a business issues bonds, it is essentially borrowing money from investors.

Bondholders: Investors who purchase bonds become bondholders and are entitled to regular interest payments and the return of the principal amount at the bond’s maturity.

Example: In India, a large infrastructure company might issue bonds to finance the construction of a new highway. Investors purchase these bonds, providing the company with the necessary funds.

Types of Bonds

Corporate Bonds: Issued by companies to raise capital for various purposes.

Government Bonds: Issued by governments to finance public projects and manage national debt.

Municipal Bonds: Issued by local governments or municipalities for funding local infrastructure projects.

How Bonds Work

Issuance: The Company sets the bond terms, including the interest rate (coupon rate), maturity date, and face value.

Interest Payments: Bondholders receive regular interest payments, typically semi-annually, based on the coupon rate.

Redemption: At maturity, the company repays the bond’s face value to the bondholders.

Example: A Japanese electronics company issues bonds with a 5% annual coupon rate, a face value of $1,000, and a 10-year maturity. Investors who buy these bonds receive $50 in interest each year and the $1,000 principal at the end of 10 years.

Advantages of Issuing Bonds

Large Capital: Bonds allow companies to raise significant amounts of capital, often more than what might be available through bank loans.

Fixed Interest Rates: Bonds typically have fixed interest rates, providing predictable interest expenses.

No Ownership Dilution: Issuing of bonds does not dilute ownership or control of the business.

Disadvantages of Issuing Bonds

Interest Obligations: Companies must make regular interest payments, which can strain cash flow if revenues are inconsistent.

Repayment at Maturity: The principal amount must be repaid in full at maturity, requiring careful financial planning.

Market Conditions: The ability to issue bonds and the interest rates offered can be affected by market conditions and the company’s credit rating.

World Around Us: Issuing Bonds

Case Study 1: Reliance Industries (India)

Background: Reliance Industries, one of India’s largest multinational, frequently issues bonds to finance its extensive operations and expansion projects.

Impact: By issuing bonds, Reliance can raise substantial capital while maintaining control over the company. For example, in 2020, Reliance raised $4 billion through a bond issuance to fund its digital services expansion.

Case Study 2: Toyota Motor Corporation (Japan)

Background: Toyota, a leading automobile manufacturer, uses both bank loans and bonds to finance its operations and R&D activities.

Impact: In 2019, Toyota issued $2 billion in green bonds to fund environmentally friendly projects, such as electric vehicle development. This helped Toyota raise capital while supporting its sustainability goals.

Case Study 3: Samsung Electronics (South Korea)

Background: Samsung Electronics, a global tech giant, uses bonds to finance its innovative projects and global expansion.

Impact: In 2021, Samsung issued $1.5 billion in bonds to fund its semiconductor manufacturing expansion, ensuring it remains competitive in the global market.

Summary

Borrowing from banks and issuing bonds are two crucial methods for businesses to raise financial capital. Each method has its advantages and challenges, and the choice depends on the business’s specific needs and circumstances. Understanding these financing options will enable you to make informed decisions and effectively manage your future business ventures.

Corporate Stock and Public Firms

Now we will delve into the world of corporate stock and public firms. Understanding these concepts is essential for grasping how businesses raise capital, distribute ownership, and operate in the financial markets. We will explore what corporate stock is, the process of going public, and the advantages and challenges faced by public firms.

Corporate Stock

Corporate stock represents ownership in a corporation. When you buy a share of stock, you own a small piece of the company.

Types of Stock:

Common Stock: Gives shareholders voting rights and a share in the company’s profits through dividends. Common shareholders are last to be paid in case of liquidation (bankruptcy).

Preferred Stock: Usually does not provide voting rights but gives shareholders a higher claim on assets and earnings than common stock. Preferred shareholders receive dividends before common shareholders.

Example: When you buy a share of Apple Inc., you become a part-owner of the company. If Apple does well, you might receive dividends and your shares may increase in value.

How Stocks Work

Initial Public Offering (IPO): When a private company offers its stock to the public for the first time, it conducts an IPO. This process raises capital for the company and allows public investors to buy shares.

Stock Exchanges: After the IPO, stocks are traded on stock exchanges, such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or the Karachi Stock Exchange (KSE). Investors buy and sell shares through these exchanges.

Example: Facebook (now Meta Platforms) conducted its IPO in 2012, raising $16 billion. This allowed the company to invest in growth and innovation while giving public investors the opportunity to own a piece of Facebook.

Going Public: The Process

Preparation for an IPO

Financial Audits: Companies must undergo rigorous financial audits to ensure transparency and accuracy in their financial statements.

Regulatory Approval: Companies need approval from regulatory bodies, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the U.S. or the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP).

Underwriters: Investment banks act as underwriter, helping to set the IPO price, buy shares from the company, and sell them to the public.

Example: Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce giant, went public in 2014 with the help of underwriters like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. It raised $25 billion, the largest IPO in history at that time.

The IPO Day

Setting the Price: The IPO price is set based on demand from institutional investors during a road show where the company presents its business model and financial health.

Trading Begins: On the IPO day, the company’s shares begin trading on the stock exchange. The price can fluctuate based on market demand.

Example: When Uber went public in 2019, its shares were priced at $45 each. On the first day of trading, the stock price varied as investors assessed Uber’s future prospects.

Public Firms

Advantages of Being Public

Access to Capital: Public firms can raise large amounts of capital by issuing additional shares. This capital can be used for expansion, research, and acquisitions.

Increased Visibility: Being listed on a stock exchange increases a company’s visibility and credibility. This can attract more investors and customers.

Liquidity: Shareholders can easily buy and sell shares, providing liquidity to their investments.

Example: Tesla has used its status as a public company to raise billions of dollars in capital, allowing it to expand its production facilities and invest in new technologies.

Challenges of Being Public

Regulatory Compliance: Public companies must adhere to strict regulatory requirements and disclose financial information regularly. This can be costly and time-consuming.

Market Pressure: Public firms face pressure from shareholders to deliver short-term results, which can conflict with long-term strategic goals.

Loss of Control: Issuing more shares can dilute ownership, potentially leading to a loss of control for the original founders and management.

Example: A company WeWork faced significant scrutiny and challenges when it attempted to go public in 2019. Regulatory and market pressures exposed weaknesses in its business model, leading to a delayed and eventually canceled IPO.

World Around Us: Public Firms

Case Study 1: Tata Motors (India)

Background: Tata Motors, a leading automobile manufacturer in India, went public to raise capital for expansion and new product development.

Impact: Being a public company has allowed Tata Motors to fund its global operations and compete in the international market. The company has used its public status to invest in electric vehicle technology and expand its product lineup.

Case Study 2: Samsung Electronics (South Korea)

Background: Samsung, a global electronics giant, is a publicly traded company that has leveraged its public status to maintain its leadership in the tech industry.

Impact: Publicly traded on the Korea Exchange, Samsung has access to substantial capital, enabling it to invest heavily in research and development. This has led to innovations in smartphones, semiconductors, and other electronic devices.

Case Study 3: Nestlé (Switzerland)

Background: Nestlé, one of the world’s largest food and beverage companies, is a public company listed on the SIX Swiss Exchange.

Impact: Nestlé’s public status has provided the capital needed for global expansion and acquisitions. It has allowed the company to maintain its market leadership in various segments, such as bottled water, infant nutrition, and pet care.

Summary

Understanding corporate stock and the dynamics of public firms is crucial for anyone interested in the financial markets. Public companies can raise substantial capital, gain visibility, and provide liquidity to investors. However, they also face challenges such as regulatory compliance, market pressure, and potential loss of control. By studying real-world examples, we can better appreciate the complexities and opportunities associated with going public.

How Firms Choose between Financial Capital Sources

We will explore how firms choose between different sources of financial capital. This is a critical decision that affects a company’s ability to grow, innovate, and remain competitive. We will discuss the various sources of financial capital, the factors influencing a firm’s choice, and real-world examples to illustrate these concepts.

Sources of Financial Capital

Internal Sources

Retained Earnings:

Profits that a company reinvests in its own operations instead of distributing to shareholders as dividends

Example: Apple reinvests a significant portion of its profits into research and development to innovate and create new products.

External Sources

Debt Financing:

Bank Loans: Borrowing money from banks with an obligation to pay back with interest.

Bonds: Issuing debt securities to investors with a promise to repay the principal amount along with periodic interest payments.

Example: The Indian Railways Finance Corporation issues bonds to raise funds for expanding railway infrastructure.

Equity Financing:

Common Stock: Issuing shares of ownership in the company.

Preferred Stock: Issuing shares that provide certain privileges over common stock, such as fixed dividends.

Example: Reliance Industries, a major Indian conglomerate, raises capital by issuing both common and preferred stock.

Factors Influencing the Choice of Financial Capital

Cost of Capital

Interest Rates: The cost of borrowing money. Lower interest rates make debt financing more attractive.

Dividend Expectations: Equity investors expect dividends, which can be a cost to the company.

Example: During periods of low-interest rates, companies like Samsung prefer to issue bonds rather than stock.

Control and Ownership

Dilution of Ownership: Issuing new shares dilutes the ownership of existing shareholders.

Retaining Control: Founders may prefer debt to avoid losing control over the company.

Example: Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg preferred retaining control, thus the company uses a dual-class stock structure to limit dilution of voting power.

Financial Flexibility

Debt Capacity: The ability of a company to take on additional debt without risking financial stability.

Access to Capital Markets: Firms with strong credit ratings have better access to capital markets for both debt and equity.

Example: Toyota has a strong credit rating, allowing it to access capital markets easily and issue debt at favorable terms.

Market Conditions

Economic Climate: Economic conditions can influence the availability and cost of capital.

Stock Market Performance: A bullish stock market might make equity financing more attractive.

Example: During economic downturns, companies might find it harder to issue stock and may prefer bank loans.

Risk and Return

Risk Tolerance: Firms with higher risk tolerance might prefer equity financing to avoid the fixed obligations of debt.

Expected Returns: Higher expected returns can justify the higher cost of equity financing

Example: Startups with uncertain cash flows, like many tech companies, often rely on equity financing.

World Around Us: Choosing Financial Capital

Background: Tata Motors needed significant capital to develop new car models and expand globally.

Case Study 1: Tata Motors (India)

Choice: The Company used a mix of debt and equity financing. It issued bonds to take advantage of low-interest rates and also raised capital through rights issues.

Outcome: This balanced approach allowed Tata Motors to fund its expansion without heavily diluting shareholder value.

Case Study 2: Samsung Electronics (South Korea)

Background: Samsung frequently invests in new technology and infrastructure.

Choice: Samsung often prefers debt financing because of its strong cash flow and credit rating, which allow it to secure low-interest loans.

Outcome: By primarily using debt, Samsung maintains control and ownership while efficiently managing its capital structure.

Case Study 3: Nestlé (Switzerland)

Background: Nestlé needs substantial capital for acquisitions and global operations.

Choice: Nestlé uses a combination of retained earnings, debt, and equity. It issues bonds to finance large acquisitions and reinvests profits for operational needs.

Outcome: This diversified approach ensures financial flexibility and stability, supporting long-term growth.

Comparing Debt and Equity Financing

Debt Financing

Advantages:

Tax Deductibility: Interest payments on debt are tax-deductible.

Avoiding Ownership Dilution: Debt does not dilute ownership

Fixed Payments: Companies can enjoy predictable repayment schedule.

Disadvantages:

Obligation to Repay: Regular interest payments can strain cash flow.

Increased Risk: High debt levels can increase financial risk.

Equity Financing

Advantages:

No Repayment Obligation: No fixed interest payments.

Risk Sharing: Equity investors share the risk of the business.

Flexibility: No immediate pressure on cash flow.

Disadvantages:

Dilution of Ownership: Issuing new shares dilutes existing ownership.

Higher Cost: Higher return expectations from equity investors.

Summary

Choosing the right source of financial capital is crucial for a firm’s success and stability. Companies must carefully evaluate the cost of capital, control considerations, financial flexibility, market conditions, and risk factors. By balancing these factors, firms can optimize their capital structure and support long-term growth.

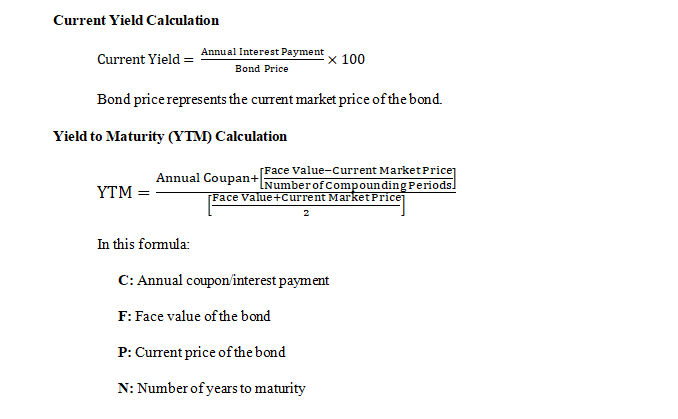

Understanding Financial Relationships and Investment Choices

Now we will delve into several key aspects of financial markets, including the relationship between savers, banks, and borrowers, calculating bond yield, contrasting different investment vehicles, and understanding the trade-offs between return and risk. These concepts are fundamental for anyone studying economics and finance.

Relationship between Savers, Banks, and Borrowers

The Role of Savers

Definition: Savers are individuals or entities that accumulate excess funds and seek to earn a return on their savings.

Example: A family saving money in a bank account for future expenses.

The Role of Banks

Definition: Banks act as intermediaries between savers and borrowers, providing a safe place for savers to deposit money and offering loans to borrowers.

Function:

Accept Deposits: Banks accept deposits from savers and offer interest on these deposits.

Provide Loans: Banks lend out these deposits to borrowers at a higher interest rate, earning a profit from the interest rate spread.

Example: A local bank accepting savings deposits from individuals and providing loans to businesses for expansion.

The Role of Borrowers

Definition: Borrowers are individuals or entities that need funds for various purposes and seek loans from banks.

Example: Company borrows money to finance the purchase of new equipment.

The Relationship

Cycle:

- Savers deposit money in banks.

- Banks lend this money to borrowers.

- Borrowers repay loans with interest.

- Banks pay interest to savers from the interest earned on loans.

Example: In Pakistan, microfinance banks collect savings from individuals and provide small loans to entrepreneurs, facilitating economic growth.

Calculating Bond Yield

Definition: Bond yield is the return an investor realizes on a bond.

Types of Yield:

Current Yield: The annual interest payment divided by the bond’s current price.

Yield to Maturity (YTM): The total return expected on a bond if held until it matures.

Contrasting Bonds, Stocks, Mutual Funds, and Assets

Bonds

Definition: Debt securities issued by entities to raise capital, with an agreement to pay interest and repay principal at maturity.

Example: Government bonds used to finance infrastructure projects.

Stocks

Definition: Equity securities representing ownership in a company.

Types:

Common Stock: Voting rights and dividends.

Preferred Stock: Fixed dividends, priority over common stock in liquidation.

Example: Buying shares of Apple Inc. and becoming a part-owner.

Mutual Funds

Definition: Investment vehicles pooling funds from many investors to invest in diversified portfolios of stocks, bonds, and other assets.

Example: Investing in a mutual fund like Vanguard 500 Index Fund, which tracks the S&P 500.

Assets

Definition: Resources owned by individuals or companies expected to provide future economic benefits.

Types:

Physical Assets: Real estate, machinery.

Financial Assets: Stocks, bonds, cash.

Example: A manufacturing company’s machinery and factory buildings.

Comparison

Risk: Stocks > Mutual Funds > Bonds

Return: Stocks > Mutual Funds > Bonds

Liquidity: Stocks > Mutual Funds > Bonds

Control: Direct with Stocks, indirect with Mutual Funds, none with Bonds.

Trade-offs Between Return and Risk

Return: The profit from an investment.

Risk: The potential for losing money on an investment.

Risk-Return Relationship

High Risk, High Return: Investments like stocks offer higher returns but come with greater risk.

Low Risk, Low Return: Investments like government bonds offer lower returns but are less risky.

Examples

Stocks: Investing in a tech startup could yield high returns but comes with the risk of losing the entire investment.

Bonds: Investing in government bonds provides steady, predictable returns with low risk.

Summary

Understanding the relationship between savers, banks, and borrowers is crucial for comprehending how financial markets function. Calculating bond yields helps investors evaluate their returns. Contrasting different investment vehicles allows investors to make informed choices. Lastly, recognizing the trade-offs between return and risk is essential for building a balanced investment portfolio.

How Capital Markets Transform Financial Flows

Capital markets play a pivotal role in transforming financial flows in an economy. They facilitate the movement of funds from savers and investors to entities that need capital for various purposes, such as businesses, governments, and individuals. This transformation of financial flows is essential for economic growth and development. Here’s a detailed explanation of how capital markets achieve this:

Mobilization of Savings

Capital markets aggregate small savings from individuals and institutions and channel them into productive investments. This process involves:

Issuance of Securities: Companies and governments issue securities, such as stocks and bonds, to raise funds.

Investment Vehicles: Mutual funds, pension funds, and other investment vehicles collect savings from a large number of investors and invest them in a diversified portfolio of securities.

Allocation of Capital

Capital markets ensure that funds are allocated to their most efficient uses. This allocation is guided by:

Price Mechanism: The prices of securities, determined by supply and demand, signal the most promising investment opportunities. Higher prices attract more capital to profitable ventures.

Risk Assessment: Credit rating agencies and market analysts provide information on the risk and return associated with different securities, helping investors make informed decisions.

Liquidity Provision

Capital markets provide liquidity, allowing investors to buy and sell securities with relative ease. This liquidity has several benefits:

Risk Management: Investors can quickly convert their investments into cash, reducing the risk associated with holding long-term securities.

Market Confidence: Liquid markets encourage more participation from investors, leading to a broader and more stable financial market.

Price Discovery

Capital markets facilitate price discovery, where the prices of securities reflect all available information about their value. This process involves:

Trading Activity: Continuous trading on stock exchanges helps in setting prices that reflect the true value of securities.

Information Flow: The availability of real-time information and transparency in trading ensures that prices are determined efficiently.

Risk Management and Diversification

Capital markets offer various instruments that help in managing and diversifying risk. These include:

Derivatives: Instruments such as options and futures allow investors to hedge against potential losses.

Diversification: Investors can spread their investments across different sectors and asset classes to minimize risk.

Facilitation of Economic Growth

By efficiently allocating capital, capital markets contribute to economic growth in several ways:

Business Expansion: Companies can raise funds for expansion, research and development, and other growth activities.

Infrastructure Development: Governments can issue bonds to finance infrastructure projects, such as roads, bridges, and schools.

Job Creation: Increased investment leads to business growth, which in turn creates jobs and reduces unemployment.

Global Capital Flow

Capital markets also facilitate the flow of capital across borders, enabling globalization of investment:

Foreign Investment: Investors can invest in foreign markets, diversifying their portfolios internationally.

Capital Inflows: Developing countries can attract foreign capital, boosting their economic development.

Examples of Capital Market Transformation

- Initial Public Offerings (IPOs)

- Case: Facebook’s IPO in 2012 raised $16 billion.

- Impact: Provided Facebook with significant capital for expansion and innovation, benefiting both the company and its investors.

- Bond Markets

- Case: U.S. Treasury Bonds are issued to fund government operations.

- Impact: These bonds provide a safe investment for individuals and institutions, while the government uses the funds for public spending.

- Venture Capital

- Case: Investments in startups like Uber and Airbnb.

- Impact: Enabled these companies to scale rapidly, transforming industries and creating substantial economic value.

Summary

Capital markets are essential for transforming financial flows, ensuring that savings are efficiently allocated to productive investments. They provide liquidity, facilitate price discovery, and offer mechanisms for risk management and diversification. Through these functions, capital markets support economic growth, infrastructure development, and global investment opportunities. Understanding how capital markets work is crucial for investors, policymakers, and businesses aiming to navigate and leverage these financial systems effectively.

A Special Case Study: The Asian Financial Crisis (1997-1998)

The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-1998 was a period of financial turmoil that affected many East and Southeast Asian countries. This case study will explore the causes, development, and consequences of the crisis, providing insights into how interconnected global economies can be vulnerable to financial shocks.

Background

In the early 1990s, many East and Southeast Asian economies experienced rapid growth, characterized by high rates of investment, booming exports, and strong capital inflows. Countries like Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines were often referred to as “Asian Tigers” due to their impressive economic performance.

Factors

Several factors contributed to this economic boom:

- Export-Led Growth: Many of these countries adopted export-oriented industrialization, focusing on manufacturing and exporting goods to developed markets.

- Capital Inflows: High interest rates and strong economic growth attracted significant foreign capital in the form of investments and loans.

- Fixed Exchange Rates: Many countries maintained fixed or semi-fixed exchange rates to the U.S. dollar, making their exports more predictable and stable.

Causes of the Crisis

- Excessive Borrowing: Governments and private sectors in these countries borrowed heavily in foreign currencies, particularly U.S. dollars. This led to high levels of external debt.

- Weak Financial Systems: Many financial institutions had poor risk management practices, weak regulatory oversight, and inadequate capital reserves.

- Currency Speculation: Fixed exchange rates became targets for currency speculation. As economic fundamentals weakened, speculators bet against these currencies, leading to downward pressure.

- Asset Bubbles: There were significant bubbles in real estate and stock markets, fueled by easy credit and speculative investments.

Asset Bubble

An asset bubble occurs when the price of a financial asset or a class of assets rises to levels significantly higher than their intrinsic value, driven by exuberant market behavior. This overvaluation is typically fueled by speculative demand, excessive optimism, and sometimes irrational investment behavior. The bubble continues to inflate until it reaches a tipping point, where a sudden realization that the assets are overvalued leads to a sharp decline in prices, often causing significant financial losses for investors and potentially triggering broader economic repercussions.

The Crisis Unfolds

- Thailand’s Currency Collapse: The crisis began in Thailand in July 1997 when the Thai baht came under speculative attack. The government was forced to float the baht, leading to a sharp devaluation.

- Contagion Effect: The crisis quickly spread to other countries in the region. Investors, fearing similar devaluations and economic problems, withdrew capital from neighboring economies, leading to financial turmoil.

- Currency Depreciation and Economic Downturn: Countries like Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines saw their currencies depreciate sharply. This led to higher debt service costs (since debt was denominated in foreign currencies) and economic recessions.

Key Events

- IMF Interventions: The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provided emergency loans to several affected countries, including Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea. These loans came with rigorous conditions, including austerity measures, structural reforms, and financial sector restructuring.

- Corporate and Bank Failures: Numerous banks and corporations in the region went bankrupt due to their inability to repay foreign-denominated debts.

- Social Unrest: Economic hardship led to widespread social unrest and political changes in several countries. For instance, Indonesian President Suharto was forced to resign in May 1998 after 31 years in power.

Consequences

- Economic Contraction: Many affected countries experienced severe economic contractions. For example:

- Indonesia: GDP contracted by 13.1% in 1998.

- Thailand: GDP contracted by 10.5% in 1998.

- South Korea: GDP contracted by 5.8% in 1998.

- Currency Depreciation: Currencies depreciated significantly against the U.S. dollar. For instance, the Indonesian rupiah lost about 80% of its value.

- Banking Sector Reform: The crisis led to significant reforms in the banking sectors of the affected countries, including stricter regulations, improved transparency, and recapitalization.

- Political Changes: The crisis precipitated political changes, including the resignation of Indonesia’s Suharto and the election of reformist governments in several countries.

Lessons Learned

- Sensible Borrowing: Excessive borrowing, especially in foreign currencies, can be dangerous. Countries need to manage external debt cautiously.

- Strong Financial Regulation: Robust financial systems with strong regulatory oversight are essential to prevent financial crises.

- Flexible Exchange Rates: Fixed or semi-fixed exchange rate systems can be vulnerable to speculative attacks. Flexible exchange rates can provide a buffer against such shocks.

- Diversification of the Economy: Relying heavily on a single economic strategy, such as export-led growth, can create vulnerabilities. Diversifying the economy can provide stability.