National Income Accounting is a framework used to measure a country’s economic performance. It provides a comprehensive picture of the nation’s income, output, and expenditure over a specific time. This chapter will explain the fundamental concepts of GDP (Gross Domestic Product), GNP (Gross National Product), and NDP (Net Domestic Product). It will also describe methods used to measure them, challenges faced during these measurements, and the circular flow of income and expenditure. Lastly, we will examine whether GDP is a good measure of a society’s well-being.

Concepts of GDP, GNP, and NDP

Understanding these key terms is essential for studying national income accounting.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is one of the most commonly used indicators to measure a country’s economic health. It represents the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders over a specific time, usually a year or a quarter.

What Does GDP Include?

GDP includes production by both domestic and foreign companies operating within a country. It accounts for every final product or service consumed, excluding intermediary products to avoid double counting.

For example: A bread manufacturer includes only the value of the final loaf of bread sold, not the value of flour used to make it.

Types of GDP

Nominal GDP

Nominal GDP is measured using current prices in the market. It does not account for changes in the price level (inflation or deflation). For instance, if a country’s economy grows but the prices of goods rise sharply, nominal GDP may appear to increase more than the real growth.

Real GDP

Real GDP adjusts for inflation to show the true growth of an economy. It reflects the actual increase in goods and services rather than price increases.

Example:

If nominal GDP grows by 10% but inflation accounts for 7%, the real GDP growth is only 3%. This method offers a clearer picture of economic health.

Case Study: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on GDP (2020)

In 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic caused sharp declines in GDP across the world. Many Asian countries faced severe disruptions in production and services. India, for example, experienced a GDP contraction of 7.3% in 2020, the worst decline since independence in 1947.

Key factors:

- Unemployment: Millions lost jobs as industries shut down.

- Health Crises: Spending shifted towards healthcare, diverting funds from other economic activities.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Lockdowns and restrictions interrupted production and exports.

Lessons Learned:

- Economies with better health infrastructure and digital readiness (like South Korea) recovered faster than others.

- Real GDP provided a clearer insight into economic recovery as inflation fluctuated during the pandemic.

Application of GDP Concepts in Behavioral Economics

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measures a country’s total economic output, but it also reveals patterns in how people behave during different economic situations. Behavioral economics studies how people’s decisions about spending and saving impact the overall economy. This connection is especially clear during times of economic uncertainty.

How Behavior Affects GDP

When people feel secure about their jobs and income, they tend to spend more on goods and services like dining out, traveling, or buying luxury items. This spending increases consumption, a key component of GDP. However, during times of uncertainty, people often save money instead of spending it. This cautious behavior reduces consumption, slowing down GDP growth.

Case Study: The 2008 Global Recession and South Asia

The 2008 Global Recession was a major economic crisis that affected countries worldwide. South Asia experienced significant impacts due to reduced global trade, job losses, and declining incomes.

How Behavior Changed:

- People in countries like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka cut back on non-essential spending.

- Families avoided buying luxury items such as new cars or electronics.

- Dining out and travel became rare as households prioritized savings.

Impact on GDP:

- In Bangladesh, GDP growth slowed from 6.4% in 2007 to 5.9% in 2008.

- Reduced consumer spending directly affected industries like retail, tourism, and manufacturing, which rely on household consumption.

Behavioral Economics in Practice

Behavioral changes during economic crises highlight the emotional and psychological factors influencing decisions. These include:

- Fear of Unemployment:

When people worry about losing jobs, they spend cautiously, reducing GDP. - Precautionary Saving:

Families save more to prepare for emergencies, decreasing demand for goods and services. - Delayed Investments:

Businesses delay expanding or hiring, leading to slower economic recovery.

Lessons from the 2008 Crisis

The 2008 Global Recession showed how changes in behavior ripple through an economy:

- Reduced spending slowed down production, forcing companies to cut jobs.

- Governments had to step in with stimulus measures to boost consumer confidence and spending.

Example of Recovery Efforts:

In 2009, India introduced stimulus packages to encourage spending on infrastructure and agriculture. These policies helped GDP rebound to 8.5% growth in 2010, showing how targeted measures can influence behavior and revive the economy.

Hence

Behavioral economics provides valuable insights into how human emotions and decisions affect GDP. During economic crises, cautious spending and saving habits reduce GDP, while government policies can help restore confidence and encourage spending. The 2008 Global Recession serves as a clear example of how behavioral changes influence economic performance, emphasizing the importance of understanding this relationship.

Case Study: Corruption and GDP Growth in South Asia

Corruption significantly impacts GDP, especially in underdeveloped countries. In Pakistan, corruption has been linked to an estimated loss of 2% to 3% of GDP annually. This loss stems from:

- Misuse of public funds.

- Evasion of taxes by businesses.

- Weak infrastructure development.

Example of Effects:

The lack of investment in education systems has kept literacy rates low, further hindering GDP growth. As of 2021, Pakistan’s literacy rate remained at around 60%, one of the lowest in the region.

Important Insight:

Investing in education and creating transparent institutions could potentially double the GDP in underdeveloped economies.

*Important Note

The statement that corruption leads to an estimated annual GDP loss of 2% to 3% in Pakistan is supported by multiple analyses of the country’s economic challenges. Research highlights that systemic corruption undermines economic growth by fostering inefficiencies, discouraging foreign investment, and exacerbating fiscal imbalances. For example:

- Research on Economic Instability: Corruption, combined with circular debt and inefficient public administration, has been identified as a major obstacle to Pakistan’s economic growth. It significantly reduces productivity and erodes public trust in institutions, impacting GDP growth ResearchGate, World Bank.

- Empirical Data Analysis: Studies such as those published by the World Bank and related academic sources confirm that governance challenges, including corruption, result in measurable economic losses, reinforcing the GDP decline estimates World Bank, Universidad de Navarra.

For a deeper understanding, you can review the sources mentioned, particularly analyses by the World Bank and detailed country-specific reports. These offer insights into the mechanisms by which corruption impacts economic variables like investment, public services, and international competitiveness.

How Wars Affect GDP: Afghanistan’s Case Study

Afghanistan has faced decades of conflict, leaving its GDP among the lowest in the world. According to the World Bank, the country’s GDP per capita was approximately $507 in 2020. The prolonged war led to:

- Destruction of infrastructure.

- Declines in agricultural and industrial output.

- Dependency on foreign aid for survival.

Recovery Efforts:

Countries like Japan and Germany, which also suffered war devastations in the past, focused on rebuilding industries to boost GDP. Afghanistan’s case shows how continuous conflict stalls this process, keeping the GDP low.

The Importance of Literacy Rates in GDP Growth

Countries with high literacy rates tend to have higher GDPs due to a skilled workforce. In Sri Lanka, for instance, literacy rates are above 92%—the highest in South Asia. This achievement has contributed to:

- Strong service industries (like IT and tourism).

- Increased productivity in agriculture.

Contrast:

In comparison, countries with low literacy rates, such as Nepal (67% literacy rate in 2021), face challenges in achieving consistent GDP growth due to a lack of skilled labor.

Hence

GDP is a vital measure of a country’s economic strength, but understanding its components and implications is essential. By studying examples like the pandemic’s impact or corruption’s role, we see how diverse factors shape GDP. For countries aiming to improve, addressing literacy, combating corruption, and ensuring stability are key steps toward sustained growth. These lessons are particularly relevant for South Asia, where economic disparities remain significant.

Gross National Product (GNP)

Gross National Product (GNP) measures the total income generated by a country’s citizens, regardless of where they live or work. It adds income earned abroad by citizens and businesses while subtracting income earned within the country by foreign residents or companies. This metric provides insight into the economic contribution of a country’s nationals globally.

Why Is GNP Important?

GNP shows the overall productivity and economic involvement of a country’s citizens. It reflects income from investments, remittances, and services provided internationally. For countries with significant diaspora populations or overseas investments, GNP can give a more accurate picture than GDP.

Key Components of GNP

Gross National Product (GNP) measures the total economic output of a country’s citizens, regardless of their location. It differs from Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by including income earned by citizens abroad and excluding income earned by foreign nationals within the country.

a. Income Earned Abroad

This includes wages, profits, and investment returns generated by citizens or businesses working or operating in foreign countries. It reflects the global economic activities of a nation’s citizens.

Details:

- Income from jobs, such as remittances sent by workers living overseas.

- Profits earned by businesses that invest or operate in foreign markets.

- Returns on international investments, such as dividends or interest payments.

Example:

A Nepalese engineer working in the Gulf region sends money back to their family in Nepal. This income is part of Nepal’s GNP because it originates from a citizen’s labor abroad.

b. Income Earned by Foreign Nationals

Income earned within a country by foreign nationals or businesses is subtracted from GDP to calculate GNP. This ensures GNP reflects only the contributions of a country’s citizens.

Details:

- Excludes profits from foreign companies operating domestically.

- Excludes wages paid to non-citizens working within the country.

Example:

If a Japanese company earns profits in Nepal, this income is excluded from Nepal’s GNP. However, it would be included in Japan’s GNP because the company is Japanese-owned.

Application of GNP: Nepal and Remittances

Nepal heavily relies on remittances sent by its citizens working abroad, which account for approximately 25% of its GNP. This is higher than its contribution to GDP, emphasizing the importance of global income for the nation’s economy.

Insights from Case Study (2021):

- Remittances supported families and contributed to education and health expenses.

- Despite COVID-19, remittances from the Gulf region and Southeast Asia remained stable due to strong familial ties.

- These funds reduced poverty but increased reliance on external income, which poses economic risks during global crises.

GNP’s Role in Policy Decisions

By highlighting the economic contributions of citizens globally, GNP helps:

- Measure a country’s dependence on external income.

- Plan policies for diaspora engagement, such as incentives for investments in the homeland.

- Highlight the need for diversification to reduce over-reliance on external sources of income.

Hence

GNP provides a more comprehensive measure of a country’s economic activity by considering global income. It reflects the contributions of citizens abroad and excludes foreign earnings within the country. The concept is particularly relevant for nations like Nepal or the Philippines, where remittances and overseas investments are significant components of economic stability.

Case Study: India’s GNP and Remittances (2020)

India has one of the largest diaspora populations globally. In 2020, Indians living abroad sent approximately $83 billion in remittances back to the country, according to the World Bank. These remittances significantly contributed to India’s GNP.

Key Factors:

- Workers in the Gulf countries accounted for over 50% of these remittances.

- Despite the global pandemic, remittances remained stable due to strong familial obligations and supportive policies in host countries.

Significance:

- These funds helped support households in rural areas, boosting consumption and reducing poverty.

- For every dollar sent back, the purchasing power increased due to the lower cost of living in India compared to countries like the US or UAE.

Behavioral Economics and GNP: The Case of Philippine Remittances

The Philippines relies heavily on remittances, contributing approximately 9.6% of its GNP in 2020. Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) work in various sectors, such as healthcare, domestic services, and construction.

Key Insights:

- Remittances from OFWs provided a safety net during economic downturns.

- Families receiving remittances invested heavily in education and healthcare, improving long-term well-being.

Challenge:

- Dependence on foreign employment can expose the country to external risks, such as immigration policies or global recessions.

GNP in War-Torn Economies: Afghanistan’s Challenges

Afghanistan has faced prolonged conflicts, which severely affected its GNP. Many Afghans fled to neighboring countries like Pakistan and Iran, sending back remittances to support their families.

Impact of War:

- A significant portion of Afghanistan’s GNP comes from remittances, as domestic economic activities remain limited.

- According to a 2019 report, approximately 20% of Afghan households relied on remittances as their primary income source.

Insight:

- For Afghanistan to increase its GNP sustainably, peace and infrastructure development are essential.

Comparison of GNP and GDP: South Korea and North Korea

South Korea’s GNP in 2021 was approximately $1.8 trillion, much larger than its GDP due to the global presence of South Korean companies like Samsung and Hyundai. In contrast, North Korea, with its isolated economy, lacks significant overseas income, leading to a much smaller GNP.

Lessons from South Korea:

- Strong exports and investments abroad boost GNP.

- Encouraging citizens to work or invest internationally can provide long-term economic benefits.

Hence

Gross National Product reflects the economic activities of a country’s citizens globally. It offers a broader perspective than GDP, especially for countries with large expatriate populations or significant foreign investments. Case studies like India and the Philippines highlight the importance of remittances, while Afghanistan and North Korea show the challenges faced by underdeveloped or conflict-affected economies. Understanding GNP helps policymakers focus on both domestic growth and international economic opportunities.

Net Domestic Product (NDP)

Net Domestic Product (NDP) is an important economic metric. It measures the total value of goods and services produced in a country, after accounting for depreciation. Depreciation is the gradual wear and tear of assets, such as machines, buildings, and equipment, that occurs during production.

Why Is Depreciation Subtracted?

Depreciation reflects the loss in value of assets over time. Ignoring this loss would give an inflated picture of a country’s actual economic performance. Subtracting depreciation ensures that NDP presents a more accurate measure of net output.

Formula:

NDP = GDP – Depreciation

Importance of NDP

NDP helps governments and policymakers understand the sustainability of economic growth. A rising GDP might seem impressive, but if depreciation is high, the actual economic gain could be much lower. NDP highlights whether an economy is growing in a way that maintains or improves its productive capacity.

Case Study: India’s Aging Infrastructure (2021)

India’s GDP was approximately $3.17 trillion in 2021. However, a large portion of its capital stock, including roads, bridges, and power plants, faced significant depreciation. A report by the Asian Development Bank estimated that depreciation accounted for nearly 10% of GDP annually.

Key insights:

- Neglected infrastructure reduced India’s ability to sustain economic growth.

- Frequent maintenance costs strained public budgets.

- High depreciation led to lower NDP compared to GDP.

NDP and the Pandemic: Lessons from Sri Lanka (2020)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Sri Lanka’s economy shrank by 3.6%, and depreciation became a significant concern. Many industries, such as tourism and manufacturing, experienced reduced operations. Machinery and equipment in factories sat idle, accelerating wear without generating revenue.

Impacts:

- Factories faced higher repair costs to restore productivity after lockdowns.

- Tourism infrastructure, such as hotels and transportation, required heavy reinvestment to attract visitors post-pandemic.

Case Study: The Role of Depreciation in Pakistan’s Power Sector (2019)

In Pakistan, outdated energy infrastructure is a major economic challenge. A report by the World Bank (2019) showed that power plants over 30 years old accounted for 60% of electricity production. These facilities had high maintenance costs and frequent breakdowns.

Key points:

- Depreciation led to energy shortages, hindering industrial growth.

- NDP in the energy sector was much lower than expected GDP contributions.

- Investing in renewable energy could reduce depreciation and improve NDP.

Behavioral Economics and Depreciation: Bangladesh’s Focus on Sustainable Assets

Bangladesh, known for its thriving garment industry, faces depreciation issues in its production facilities. Over-reliance on low-cost machinery has resulted in faster wear and tear. In 2022, manufacturers began adopting longer-lasting, sustainable equipment, supported by incentives from the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Results:

- Factories with newer equipment saw a 15% rise in efficiency.

- Depreciation costs declined, improving overall NDP.

Comparison of Developed and Developing Countries

Developed countries often invest in maintaining their infrastructure, which keeps depreciation rates low. For example:

- In Japan, only 3-5% of GDP is lost to depreciation annually, thanks to regular upgrades.

- In contrast, developing countries like Nepal lose nearly 12% of GDP due to poor infrastructure maintenance.

How NDP Reflects Economic Challenges

NDP is a better measure than GDP for countries facing economic struggles, such as underdevelopment or war. In conflict-ridden economies, infrastructure suffers massive depreciation, resulting in low NDP. For example, in Syria (2016), depreciation accounted for nearly 20% of GDP, primarily due to destroyed infrastructure.

Hence

Net Domestic Product highlights the true economic health of a nation by accounting for depreciation. While GDP shows the overall production, NDP ensures that losses from aging infrastructure or poor maintenance are considered. Case studies from South Asia and other regions reveal how depreciation impacts growth, especially in underdeveloped countries. Policymakers can use NDP to prioritize investments in sustainable infrastructure and ensure long-term economic stability.

Measurement Techniques and Challenges

Measuring national income involves different methods. Each has its strengths and weaknesses. The measurement techniques differ for GDP, GNP, and NDP as they each focus on different aspects: GDP measures domestic production, GNP includes citizens’ global income, and NDP adjusts GDP by subtracting depreciation.

Approaches to Measure GDP in Different Situations

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) can be measured using three main approaches: the production approach, the income approach, and the expenditure approach. Each approach is suited to specific scenarios, depending on the economic activity being studied, the availability of data, and the goals of the analysis.

1. Production Approach

The production approach measures GDP by calculating the total value of goods and services produced in an economy. It focuses on the output of industries and excludes intermediary goods to avoid double counting.

When to Use This Approach:

- When assessing the performance of specific industries like agriculture, manufacturing, or services.

- Suitable for economies with well-defined sectors and reliable production data.

Case Study: Vietnam’s Agricultural Growth (2019)

Vietnam is one of the leading exporters of rice, coffee, and seafood. The production approach was ideal for measuring GDP in its agricultural sector, which accounted for 14% of total GDP in 2019.

Key insights:

- Precise data on crop yields and exports allowed accurate GDP estimation.

- Policymakers used these figures to plan investments in rural infrastructure and technology.

2. Income Approach

The income approach calculates GDP by summing up all the incomes earned in an economy, including wages, rents, profits, and taxes. This approach highlights how income is distributed among different groups.

When to Use This Approach:

- When the focus is on income disparities, labor market conditions, or tax revenue analysis.

- Useful for understanding the impact of policies on wages and household incomes.

Case Study: Bangladesh’s Garment Industry (2020)

The garment industry is the backbone of Bangladesh’s economy, employing over 4 million workers and contributing to 11% of GDP.

Key insights:

- The income approach revealed that 80% of wages were paid to female workers, highlighting the sector’s role in empowering women.

- Policymakers used these findings to develop wage protection schemes during the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring stability for low-income workers.

3. Expenditure Approach

The expenditure approach calculates GDP by summing up total spending on goods and services. It includes consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports.

- Adds up total spending on goods and services.

- Formula: GDP = Consumption + Investment + Government Spending + Net Exports

When to Use This Approach:

- When analyzing consumer behavior, government spending, or trade balances.

- Best for economies where consumer spending or exports are key growth drivers.

Case Study: India’s Economic Recovery Post-Lockdown (2021)

After the COVID-19 lockdowns, India’s government launched a stimulus package to boost spending. This included direct cash transfers and subsidies.

Key insights:

- The expenditure approach highlighted that private consumption rebounded by 6% in the second half of 2021.

- The approach also revealed that infrastructure investments rose by 8%, driven by government spending.

Scenario: Choosing the Best Approach in an Emerging Economy

Consider Nepal, a developing country heavily dependent on tourism, remittances, and agriculture. To accurately measure GDP, the following approaches can be used in different contexts:

- Production Approach for Agriculture

Agriculture contributes over 20% of Nepal’s GDP. Measuring crop yields, livestock production, and export volumes provides accurate GDP estimates. - Income Approach for Remittances

Remittances account for approximately 25% of Nepal’s GDP (2021). The income approach captures the earnings sent by workers abroad, providing insights into the economic reliance on expatriates. - Expenditure Approach for Tourism

Tourism drives consumer spending on hotels, transportation, and cultural activities. The expenditure approach can track how tourist inflows contribute to GDP.

Case Study: Afghanistan’s Use of the Production Approach (2020)

Afghanistan’s economy relies on agriculture and mining. In 2020, agriculture contributed nearly 30% of GDP. The production approach was used to estimate GDP, focusing on:

- Wheat production, which accounted for 45% of agricultural output.

- Exports of fruits like pomegranates and saffron.

Challenges:

- Lack of reliable data due to conflict and poor infrastructure.

Seasonal variations in output complicated measurements.

Measurement Techniques for GNP and Challenges

Gross National Product (GNP) measures the total income earned by a country’s citizens and businesses, regardless of where they are located. To calculate GNP, specific techniques and data sources are required, but these also come with challenges in implementation.

Measurement Techniques for GNP

1. Income Approach:

- Calculates GNP by summing up all incomes earned by citizens and businesses, including:

- Wages and salaries earned abroad.

- Profits from overseas investments.

- Dividends, interest, and rent received from foreign entities.

- Subtracts income earned domestically by foreign nationals or entities.

2. Expenditure Approach:

Adds up total spending by citizens on goods and services globally, factoring in investments abroad.

Includes private consumption, net exports, and foreign-earned income.

Data Sources Used:

National and international banking records for remittances.

Surveys and financial disclosures from businesses.

Government reports on overseas investments and earnings.

Challenges in Measuring GNP

- Data Collection Issues:

- Accurate data on remittances and foreign investments is difficult to gather, especially in informal economies.

- Underreporting by citizens or businesses complicates estimates.

- Inclusion of Informal Earnings:

- Many overseas workers send money through informal channels that may not be recorded officially.

- Currency Exchange Fluctuations:

- Changes in currency values impact the real worth of foreign earnings, creating inconsistencies in GNP calculations.

- Double Counting:

- Ensuring income from investments and remittances isn’t counted in both the host and origin countries.

- Political and Legal Barriers:

- Restrictions on data sharing between nations can hinder access to complete financial records.

Case Study 1: Philippines and Remittances (2020)

The Philippines is one of the largest recipients of remittances globally. In 2020, Filipino workers abroad sent home approximately $34.9 billion, accounting for nearly 10% of the GNP.

Key Insights:

- The income approach was crucial for including remittances as a major component of GNP.

- Challenges arose in capturing data from informal channels, as a significant portion of remittances bypass formal banking systems.

- Government programs, such as incentivizing remittance transfers through formal channels, helped improve accuracy.

Impact:

- GNP figures provided a more comprehensive view of economic dependence on overseas workers, informing policies to support worker rights abroad and invest in local job creation.

Case Study 2: Nepal and Diaspora Contributions (2019)

In Nepal, remittances accounted for approximately 25% of the GNP in 2019. Most of these funds came from workers in Gulf countries and Malaysia.

Challenges Faced:

- Reliance on informal data collection led to underreported income figures.

- Currency volatility impacted the actual value of remittances in local terms.

Resolution:

- Nepal’s government partnered with international banks to streamline remittance reporting.

- Accurate GNP data helped highlight economic vulnerabilities and the need to reduce dependency on external income.

Hence

Measuring GNP requires advanced methodologies and reliable data sources, but challenges like underreporting, informal channels, and data-sharing restrictions persist. Case studies from the Philippines and Nepal showcase both the reliance on remittances for GNP and the difficulties in capturing accurate figures. Improved financial systems and global cooperation can enhance the accuracy and utility of GNP calculations.

Measurement Techniques for NDP and Challenges

Net Domestic Product (NDP) is derived by subtracting depreciation (the loss in value of physical assets) from the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). NDP measures the net output after accounting for the wear and tear on assets used in production, offering a realistic picture of sustainable economic growth.

Measurement Techniques for NDP

GDP Estimation:

- Start with GDP, which measures the total value of goods and services produced in a country.

- Use the production, income, or expenditure approach to calculate GDP.

Depreciation Calculation:

- Depreciation is the annual reduction in the value of assets like machinery, buildings, and equipment.

- Estimates are made using historical costs, asset lifespans, and usage data.

- Depreciation is recorded in financial statements and national accounts.

NDP Calculation Formula:

- NDP = GDP – Depreciation

Challenges in Measuring NDP

- Accurate Depreciation Estimates:

- Depreciation is difficult to measure due to variations in asset lifespans and usage patterns.

- Inconsistent accounting standards lead to errors in depreciation reporting.

- Inclusion of Informal Sectors:

- Many economies, particularly in developing countries, have large informal sectors where depreciation is rarely recorded.

- This underestimates the actual wear and tear on assets.

- Technological Changes:

- Advances in technology can render assets obsolete faster than anticipated, making standard depreciation rates inaccurate.

- Asset Maintenance and Repairs:

- Maintenance extends the useful life of assets, complicating depreciation calculations.

- Variations in maintenance practices across sectors can distort results.

- Limited Data Availability:

- Developing countries often lack comprehensive data on asset ownership and conditions.

- This limits the accuracy of depreciation estimates.

Case Study: Japan’s Asset Management Approach (2018)

Japan uses advanced methods to calculate depreciation and its impact on NDP. The government tracks assets extensively using digital systems to measure wear and tear.

Key Insights:

- In 2018, depreciation accounted for approximately 16% of Japan’s GDP.

- High investment in maintenance minimized depreciation, ensuring stable NDP growth.

- Japan’s approach highlights the importance of robust data collection and asset management systems.

Challenges Addressed:

- By adopting advanced accounting techniques, Japan reduced errors in depreciation estimates.

- Integration of technological solutions improved the tracking of asset usage and replacement needs.

Case Study: Depreciation Challenges in India’s Infrastructure Sector (2021)

India faces significant depreciation issues due to aging infrastructure and insufficient maintenance. In 2021, it was estimated that 10-15% of GDP was eroded due to depreciation.

Challenges Identified:

- Lack of consistent asset valuation techniques led to undervaluation of depreciation.

- Poor maintenance of public infrastructure, such as roads and bridges, accelerated asset deterioration.

Policy Measures:

- The government initiated infrastructure audits to improve asset monitoring.

- Increased budget allocation for repairs helped slow depreciation, improving NDP estimates.

Hence

NDP offers a more realistic measure of economic health by accounting for asset depreciation. While developed countries like Japan lead in accurate measurements through advanced systems, challenges persist in developing economies due to informal sectors, limited data, and outdated practices. Case studies from Japan and India underline the need for robust systems and policies to improve NDP calculations.

Measuring Economic Performance in the AI and Social Media Era

In the era of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and social media, economies are becoming increasingly interconnected, creating a global village. Traditional GDP measurement methods may fail to capture the nuances of digital and networked economies. The Expenditure Approach, augmented with AI-driven analytics, is emerging as a superior method. This approach incorporates data from digital transactions, e-commerce, and social media-driven consumption patterns.

Why the Expenditure Approach with AI?

- Captures Digital Consumption:

- Tracks spending on e-commerce platforms and digital services like cloud computing, social media advertising, and streaming subscriptions.

- Real-Time Data:

- AI processes real-time data from online transactions, enabling more accurate and dynamic GDP measurements.

- Global Transactions:

- Measures cross-border digital activities, such as freelance work facilitated by platforms like Upwork or Fiverr.

- Behavioral Insights:

- AI analyzes consumer behavior on social media to estimate spending trends, including impulsive purchases influenced by targeted ads.

Case Study: India’s Digital Economy Transformation (2020-2022)

India is a leading example of how AI and social media influence economic measurement. The government’s Digital India Initiative and the rapid adoption of platforms like Amazon, Flipkart, and social media channels revolutionized consumer behavior.

Key Insights:

- In 2021, digital payments through platforms like UPI (Unified Payments Interface) crossed $2.2 trillion, reflecting a massive shift to cashless transactions.

- AI was used to analyze consumer spending during online festivals like Flipkart’s Big Billion Days and Amazon’s Great Indian Festival. These events contributed significantly to GDP through e-commerce sales.

- Social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook influenced purchasing decisions, with small businesses leveraging these tools to sell directly to consumers.

Challenges:

- Informal sectors and unrecorded transactions remain outside the digital economy’s scope.

- Privacy concerns limit the amount of data AI can process for GDP calculations.

Impact:

- AI-driven insights helped India improve GDP accuracy by reflecting digital consumption trends.

- Policymakers used this data to promote digital infrastructure, boosting e-commerce and online entrepreneurship.

The Role of AI in Enhancing Global Measurement

- Case of Estonia’s Digital Economy:

Estonia, one of the most digitally advanced nations, uses e-residency programs and AI to track the economic activities of global entrepreneurs who base their operations in the country. This approach enables Estonia to include remote income in GDP. - Social Media Monetization in the US (2021):

Platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok contributed significantly to the creator economy, with estimates valuing this sector at over $100 billion. AI helped estimate contributions from these digital platforms to GDP by analyzing ad revenue and influencer-driven commerce.

Hence

In the AI and social media era, the Expenditure Approach enhanced by AI analytics is the most effective method to measure economic performance. Real-world examples from India, Estonia, and the US demonstrate how integrating AI with traditional methods captures the complexities of modern economies, offering policymakers actionable insights.

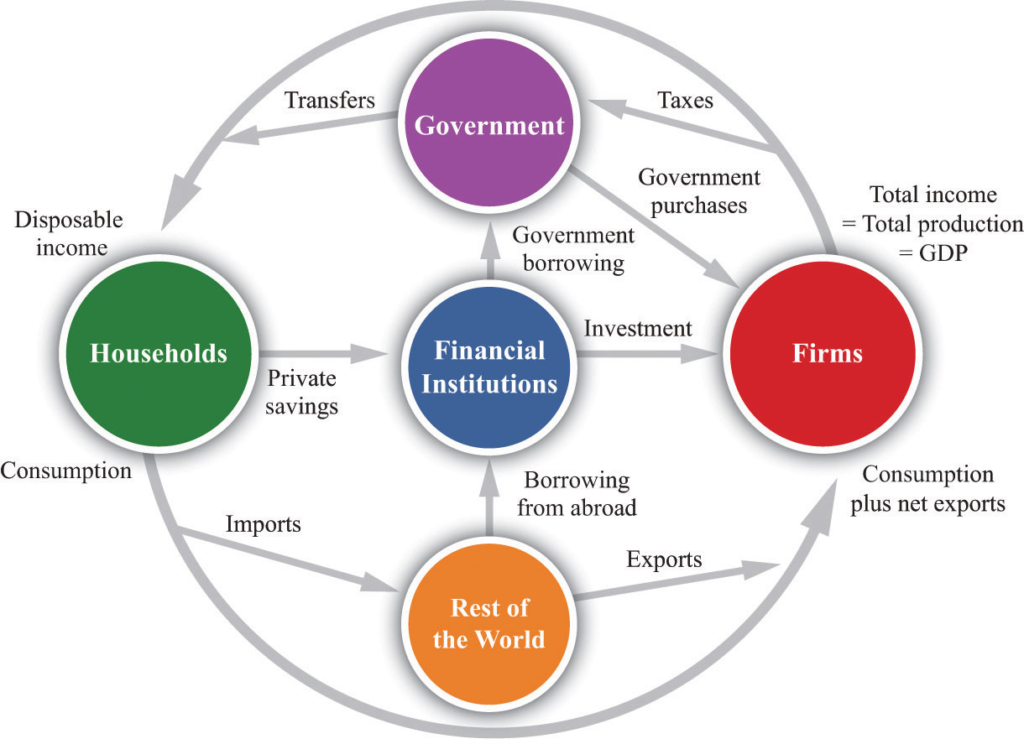

Circular Flow of Income and Expenditure

The Circular Flow of Income and Expenditure is a fundamental model in macroeconomics that explains how money moves within an economy. It highlights the continuous interaction between two key sectors: households and firms. This model shows the interdependence of production, income, and consumption, forming the backbone of any economic system.

Key Components of the Circular Flow

Households:

- Households provide labor, capital, and land to firms.

- They earn wages, rent, and profits in exchange for these resources.

- They spend their income on goods and services produced by firms.

Firms:

- Firms produce goods and services using the resources supplied by households.

- They pay wages, rent, and profits to households for these resources.

- Firms generate revenue when households purchase their products.

The Flow of Money in the Economy

- From Households to Firms:

Households spend money on goods and services produced by firms. This spending constitutes the expenditure flow. - From Firms to Households:

Firms use the revenue earned to pay wages, rent, and profits to households. This forms the income flow.

The cycle is continuous, as income earned by households is spent on goods and services, which, in turn, fuels the production by firms.

World Around Us: Circular Flow of Income

Case Study 1: India’s Rural Economy and the Circular Flow (2021)

In India, the rural economy depends heavily on the circular flow model. Farmers (households) supply crops to firms (food processing units). These firms produce packaged goods sold back to rural and urban households.

Key Insights:

- Farmers receive income from firms and use it to purchase seeds, fertilizers, and consumer goods.

- Firms rely on this spending to sustain production.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, disruptions in the flow (e.g., halted transportation and reduced consumer spending) caused significant challenges. Studies estimated that rural spending fell by 15% in 2020, breaking the circular flow temporarily.

Case Study 2: Bangladesh’s Garment Industry (2020)

The garment industry in Bangladesh exemplifies the circular flow. Here, households provide labor to garment factories (firms), which produce clothing for domestic and global markets.

Key Facts:

- The industry employs 4 million workers, predominantly women.

- Workers earn wages that are spent on food, housing, and education.

When global demand fell in 2020, factories reduced production, and wages were cut. This broke the flow, reducing consumer spending and affecting local businesses dependent on garment workers’ incomes.

Case Study 3: Japan’s Post-War Reconstruction (1950s)

After World War II, Japan used the circular flow model to rebuild its economy. Households saved and invested heavily in industrial firms, enabling rapid production growth. Firms reinvested earnings to create jobs, restarting the cycle of production and income.

Impact:

- By the 1960s, Japan’s GDP grew by 10% annually, driven by the uninterrupted circular flow of income and expenditure.

Challenges to the Circular Flow

- Economic Disruptions:

Events like pandemics, wars, or natural disasters can break the cycle by reducing production or consumer spending. - Inequality:

If income distribution is skewed, households may not have enough money to sustain spending, affecting firms’ revenues. - External Trade Factors:

In open economies, imports and exports influence the circular flow. For example, if a country imports more than it exports, money leaves the domestic circular flow.

Hence

The circular flow of income and expenditure illustrates the interconnectedness of households and firms in sustaining economic activity. Real-world cases, such as India’s rural economy and Bangladesh’s garment sector, demonstrate the model’s relevance. However, disruptions like economic crises can break the cycle, highlighting the importance of policies that ensure its continuity.

Using GDP to Compare Economic Welfare Between Nations

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a key indicator used to assess and compare the economic performance of nations. However, for a fair comparison, adjustments such as currency conversion and GDP per capita are necessary.

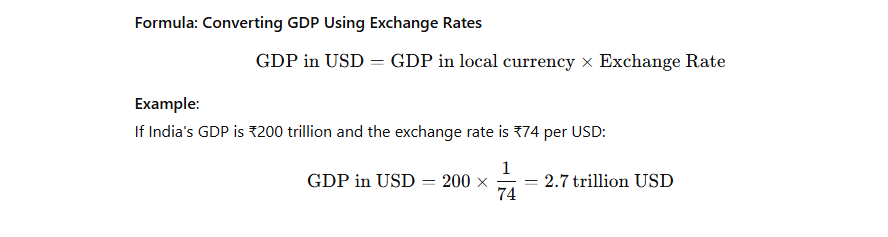

Comparing GDP Using Exchange Rates

To compare GDP across nations, GDP values must be converted into a common currency, often US dollars (USD). This is done using exchange rates, which reflect the relative value of one country’s currency against another.

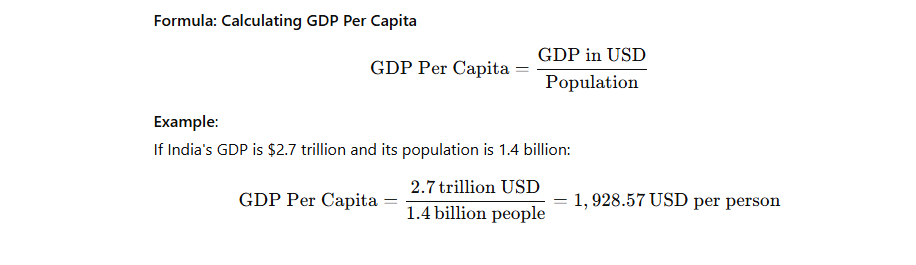

Adjusting for Population: GDP Per Capita

GDP per capita measures the average economic output per person and is calculated by dividing the GDP by the population. It provides a clearer picture of individual economic welfare.

Case Study: Comparing Economic Welfare – USA vs. Bangladesh (2022)

GDP:

- USA: $23 trillion

- Bangladesh: $416 billion

Population:

- USA: 332 million

- Bangladesh: 167 million

Hence

GDP comparisons using exchange rates and per capita adjustments provide a meaningful way to evaluate economic welfare across nations. By considering population and currency values, policymakers and economists can better understand relative economic performance and living standards.

How Well GDP Measures the Well-Being of Society

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is widely used to measure the economic performance of a country. While it is a valuable indicator of production and growth, it has limitations when assessing the overall well-being of a society. Understanding its strengths and weaknesses provides a clearer perspective on its role in evaluating economic health.

Strengths of GDP as a Measure

1. Economic Growth Indicator

GDP is a reliable measure of economic progress. When GDP rises, it often indicates increased production, better job opportunities, and higher income levels.

- Example: During China’s economic boom (2000-2020), its GDP grew from approximately $1.2 trillion to over $14.7 trillion, signaling massive industrial growth. This expansion created millions of jobs, reduced poverty, and increased household incomes.

2. International Comparisons

GDP provides a standard way to compare the economic performance of countries. It helps identify leaders in growth and areas needing improvement.

- Example: In 2020, Bangladesh surpassed India in GDP per capita, reaching $2,064 compared to India’s $1,947. This comparison highlighted Bangladesh’s progress in manufacturing and poverty reduction despite being a smaller economy.

Limitations of GDP

1. Excludes Non-Market Activities

GDP does not account for unpaid work, such as caregiving and household chores, which are crucial for societal well-being. It also ignores informal economies common in developing nations.

- Example: In South Asia, informal economies contribute significantly to daily life. For instance, in Pakistan, informal markets account for up to 36% of the economy, according to the IMF (2021). These activities are critical but remain uncounted in GDP.

2. Ignores Income Distribution

GDP measures total output but does not reflect how wealth is shared. A high GDP does not ensure equitable wealth distribution.

- Example: In India, despite a GDP growth rate of 8% in 2018, income inequality widened, with the richest 10% owning nearly 77% of the wealth.

3. Environmental Costs

Economic activities contributing to GDP, such as mining and deforestation, often harm the environment. This damage can reduce long-term well-being.

- Example: Indonesia’s palm oil industry boosted GDP but led to widespread deforestation. According to a 2019 report, this deforestation increased carbon emissions and reduced biodiversity, impacting global climate health.

Case Study: Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (GNH)

Bhutan offers an alternative approach by focusing on Gross National Happiness (GNH) rather than GDP alone.

- Key Features: GNH measures societal well-being through factors like cultural preservation, environmental conservation, and equitable development.

- Impact: Bhutan’s policies prioritize environmental sustainability and community happiness. For instance, over 70% of Bhutan’s land remains forested, and the country offsets more carbon than it produces.

Hence

While GDP is a useful tool for measuring economic activity, it does not fully capture societal well-being. Factors like unpaid work, income inequality, and environmental health remain unaccounted for. Alternative approaches, like Bhutan’s GNH, provide broader insights into societal welfare. Policymakers should use GDP alongside other metrics to develop a holistic understanding of a nation’s progress.

Research Suggestions

Following topics and questions provide a foundation for impactful research, emphasizing their relevance to current global challenges and economic trends.

Space Economy

- Potential Areas of Study:

- The impact of satellite-based internet on global communication and its economic implications.

- Private space companies (e.g., SpaceX, Blue Origin) and their role in transforming national GDPs.

- Space mining and its potential to disrupt resource economies.

- Research Question:

- How does the commercialization of space affect global trade and resource distribution?

- Suggested Case Study:

- Analyze the European Space Agency’s (ESA) contribution to the European economy (2020-2023).

Behavioral Economics

- Potential Areas of Study:

- The role of human biases in decision-making during financial crises.

- Nudging as a tool for sustainable consumption patterns.

- Research Question:

- How do psychological factors influence saving behaviors in developing economies during global crises?

- Suggested Case Study:

- Study India’s use of behavioral incentives during the COVID-19 lockdown to promote health and economic activity.

AI and Social Media-Based Digital Economy

- Potential Areas of Study:

- AI’s role in shaping consumer behavior through predictive analytics.

- The gig economy’s evolution through AI-powered platforms like Uber and TaskRabbit.

- Research Question:

- How does AI-driven advertising affect spending patterns on social media platforms?

- Suggested Case Study:

- The impact of Instagram and TikTok commerce on small businesses in Southeast Asia (2020-2022).

Blue Economy

- Potential Areas of Study:

- Marine renewable energy as a pathway to sustainable economic growth.

- The economic potential of coastal and underwater tourism.

- Research Question:

- How can small island nations use the blue economy to achieve sustainable development?

- Suggested Case Study:

- Mauritius’s strategy for promoting the blue economy as a GDP driver (2018-2022).

Sustainable Growth and Environmental Economics

- Potential Areas of Study:

- The role of carbon pricing in reducing industrial emissions.

- Circular economy models for waste reduction in urban areas.

- Research Question:

- What are the economic benefits of transitioning to renewable energy in low-income countries?

- Suggested Case Study:

- Germany’s transition to renewable energy under the Energiewende program and its effects on GDP (2010-2023).

Income Inequality

- Potential Areas of Study:

- The impact of wealth taxes on reducing income inequality.

- Gender-based pay gaps and their long-term effects on economic growth.

- Research Question:

- How does income inequality influence political stability in emerging economies?

- Suggested Case Study:

- South Africa’s experience with income redistribution policies post-apartheid (1994-2022).

The Welfare State

- Potential Areas of Study:

- Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a response to automation-driven unemployment.

- Comparative analysis of Nordic welfare models versus emerging economies.

- Research Question:

- How do welfare policies influence labor market participation in high-income countries?

- Suggested Case Study:

- Finland’s UBI trial and its impact on employment and mental health (2017-2019).

Unemployment

- Potential Areas of Study:

- The impact of automation on structural unemployment.

- Green jobs as a solution to labor market disruptions in traditional industries.

- Research Question:

- What strategies can developing nations adopt to counter long-term youth unemployment?

- Suggested Case Study:

- Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and its focus on reducing unemployment through economic diversification.

Global Economic Crises

- Potential Areas of Study:

- Comparative analysis of fiscal and monetary responses to economic downturns.

- Supply chain resilience strategies in the aftermath of global crises.

- Research Question:

- How do global economic crises affect poverty rates in low-income countries?

- Suggested Case Study:

- A comparison of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic’s economic impacts in Southeast Asia.

Critical Thinking

- Is China going to eclipse the United States in terms of standard of living?

- Conceptual Understanding:

- How do traditional metrics like GDP and GNP capture (or fail to capture) the contributions of modern sectors like the space economy or digital economy?

- Should national income accounting incorporate behavioral insights, such as consumer sentiment and social media-driven consumption, to better measure economic activity?

- Challenges in Measurement:

- What challenges arise when trying to quantify the economic contributions of non-traditional sectors, like marine biodiversity in the blue economy or carbon trading in environmental economics?

- Specific Applications:

- How would the inclusion of satellite-based services and space exploration investments affect GDP measurement?

- Should income generated from space mining be classified as domestic or global production in national accounts?

- Global Comparisons:

- How do countries investing in the space economy, such as the US and India, differ in their accounting for space-related economic activity in GDP?

- Consumer Behavior:

- How does the role of consumer spending on digital platforms impact traditional measures of national income?

- Can shifts in consumer behavior during economic crises (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) highlight gaps in current national income accounting methods?

- Modern Economic Activity:

- How should national income accounts capture the value created by influencers, content creators, and gig workers in the digital economy?

- Can the use of AI in e-commerce and advertising be quantified as part of a nation’s productivity, and how should it be recorded?

- Sustainability Integration:

- Should environmental degradation from industrial production be subtracted from GDP to reflect sustainable growth more accurately?

- How can the blue economy’s contributions, like offshore wind energy or sustainable fisheries, be measured alongside traditional sectors?

- Equitable Growth:

- Why does a rising GDP not necessarily indicate reduced income inequality?

- How can national income accounting be adapted to capture the distribution of wealth and income more effectively?

- Public Services:

- How does investment in welfare programs (e.g., healthcare, pensions) reflect in national income measurements?

- Should unpaid caregiving and domestic work be included in GDP calculations to better represent societal contributions?

- Economic Resilience:

- How do unemployment rates and job market disruptions during global crises impact GDP and NDP calculations?

- Should governments account for lost productivity during crises (e.g., pandemics or wars) in a separate economic metric?

- Case Studies:

- How do welfare policies in Scandinavian countries differ in their reflection within GDP versus GNP compared to developing nations?

- Long-Term Metrics:

- Should GDP growth be redefined to include long-term sustainability metrics such as renewable energy investments or education spending?

- How can GDP be adjusted to discourage activities that harm the environment while promoting sustainable practices?

- Policy Implications:

- How does national income accounting influence policymaking in sectors like AI-driven automation or marine conservation?

- Should policymakers prioritize GDP growth over alternative measures of societal well-being, such as Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (GNH)?

- Global Comparisons:

- How do economic crises like the 2008 Recession or COVID-19 highlight the limitations of GDP in measuring national well-being?