Today, we will discuss a crucial topic in our economics course: Monopolistic Competition. This market structure is widely observed in many industries worldwide, including in our own country.

Imperfect Competition

Monopolistic competition is an imperfectly competitive market. Unlike perfect competition, it has elements of both competition and monopoly. It represents the producers of differentiated products competing in the market.

Key Characteristics

- Many Firms: There are numerous firms in the market.

- Differentiated Products: Each firm offers products that are slightly different from each other.

- Free Entry and Exit: Firms can enter or exit the market easily.

Significance of Differentiated Products

Product differentiation is a key feature of monopolistic competition. It refers to the process by which firms make their products distinct from those of their competitors. This distinction can be achieved through various means:

1. Features and Quality

Products can differ in terms of features and quality. For instance, consider toothpaste brands like Colgate, Pepsodent, and Sensodyne:

- Colgate: Known for its anti-cavity protection and wide range of flavors.

- Pepsodent: Often marketed for its teeth-whitening properties.

- Sensodyne: Specifically targets consumers with sensitive teeth.

Each brand offers unique features that appeal to different consumer needs and preferences.

2. Branding and Packaging

Branding and packaging play a significant role in product differentiation. The design, color, and overall aesthetic of a product’s packaging can influence consumer perception and preference. For example:

- Coca-Cola: Recognizable for its iconic red and white branding and the distinctive bottle shape.

- Pepsi: Differentiates itself with a blue theme and youthful, energetic marketing campaigns.

3. Price

Differentiation can also occur through pricing strategies. Premium brands may set higher prices to signal higher quality, while budget brands may compete on affordability. For example:

- Apple: Sells its products at a premium price, emphasizing innovation and high quality.

- Xiaomi: Known for offering feature-rich smartphones at lower prices, appealing to cost-conscious consumers.

4. Location and Accessibility

Firms may differentiate themselves based on their location and accessibility. For instance, local grocery stores may offer personalized services and convenience, while large supermarkets provide a wide variety of products under one roof.

5. Customer Service

High-quality customer service can be a differentiating factor. Companies like Amazon have built their reputation on excellent customer service, including easy returns and fast delivery, setting them apart from competitors.

Impact on Consumer Choice

Product differentiation has a profound impact on consumer choice, enhancing the overall consumer experience in several ways:

1. Variety of Options

Differentiated products provide consumers with a broad spectrum of choices. This variety ensures that consumers can find products that closely match their individual preferences and needs. For instance, in the smartphone market, consumers can choose from a range of brands, each offering unique features such as camera quality, battery life, and user interface.

2. Brand Loyalty

When consumers find a brand that meets their specific needs and preferences, they are likely to develop brand loyalty. For example, a consumer who values sustainability may consistently choose brands like Patagonia for their commitment to environmental responsibility.

3. Enhanced Satisfaction

With differentiated products, consumers can select items that provide the highest level of satisfaction. This satisfaction comes from finding products that not only meet their functional needs but also align with their personal values and lifestyles.

4. Competitive Prices and Quality

Product differentiation fosters competition among firms to improve quality and offer competitive prices. This competition benefits consumers as companies strive to innovate and enhance their products. For instance, in the airline industry, companies differentiate themselves through service quality, pricing, in-flight amenities, and loyalty programs.

World Around Us: Differentiated Products

India: In the Indian food market, brands like Amul’s and Mother Dairy differentiate their dairy products through taste, packaging, and regional preferences. Amul’s butter is known for its distinct flavor, while Mother Dairy offers a range of milk products catering to different dietary needs.

Japan: Japanese electronics brands like Sony and Panasonic are known for their innovation and quality. Sony differentiates its products through cutting-edge technology and sleek design, appealing to tech-savvy consumers.

Germany: In the automotive industry, brands like BMW and Audi are differentiated by their engineering excellence and luxury appeal. BMW emphasizes a sporty driving experience, while Audi focuses on advanced technology and comfort.

France: French fashion houses like Chanel and Dior differentiate themselves through high-end, exclusive designs, catering to the luxury segment of the market.

China: The smartphone market in China is highly competitive, with brands like Huawei and Oppo differentiating themselves through innovative features and aggressive pricing. Huawei’s high-end models compete with global brands, while Oppo targets younger consumers with stylish designs and advanced camera capabilities.

Summary

In summary, product differentiation in monopolistic competition leads to a wide variety of choices for consumers, catering to their diverse preferences and needs. By understanding how firms differentiate their products, we can appreciate the dynamic nature of markets and the benefits they bring to consumers globally. This differentiation not only enhances consumer satisfaction but also drives innovation and competition among firms.

3. Perceived Demand for a Monopolistic Competitor

We have discussed that the perceived demand is the demand curve that a firm believes it faces, indicating the quantity of its product that consumers will buy at different prices.

Downward Sloping Demand Curve

In monopolistic competition, unlike perfect competition, firms face a downward-sloping demand curve. This curve indicates that a firm has some control over the price of its product. The price it can charge is inversely related to the quantity demanded. If the firm wants to sell more, it must lower the price, and if it raises the price, it will sell less.

Importance

The downward-sloping demand curve reflects the unique position of firms in monopolistic competition. Each firm sells products that are differentiated from its competitors. This differentiation gives the firm some market power to set prices above marginal cost without losing all its customers.

Example

Consider a clothing store. This store offers a unique style and brand of clothing that is slightly different from other stores. If it lowers its prices, it can attract more customers who might otherwise shop elsewhere. Conversely, if it raises its prices too much, customers will go to competing stores that offer similar clothing at lower prices.

Graphical Representation

- Perfect Competitor (Figure 12.1a):

The demand curve for a perfect competitor is horizontal, indicating that the firm can sell any quantity of goods at the prevailing market price. This is because there are many sellers of identical products, and no single firm can influence the market price.

- Monopoly (Figure 12.1b):

The demand curve for a monopoly is downward sloping. This means the monopolist can set the price, but to sell more, it must lower the price. The monopolist is the sole supplier or producer of the product, so it faces the entire market demand.

Figure 12.1 Perceived Demand for Firms in Different Competitive Settings

- Monopolistic Competitor (Figure 12.1c):

Similar to a monopoly, a monopolistic competitor also faces a downward-sloping demand curve. However, this curve is typically more elastic than that of a monopoly. It means the firm has some, but not complete, control over the market price. The firm’s ability to set the price depends on how differentiated its product is from competitors.

Key Points to Remember:

- Differentiated Products: Each firm’s product is slightly different from those of its competitors, giving it some market power.

- Price and Quantity Relationship: Firms can influence the market price but must consider how price changes will affect the quantity demanded.

- Consumer Choice: Consumers benefit from having a variety of choices, which cater to their individual preferences and needs.

By understanding these concepts, you can better anticipate the dynamics of monopolistic competition and how firms operate within this market structure.

Pricing and Quantity Decisions in Monopolistic Competition

Profit Maximization

In monopolistic competition, firms maximize their profits by producing the quantity of goods where their marginal revenue (MR) equals their marginal cost (MC). Here is a step-by-step explanation of how firms decide on pricing and quantity:

- Marginal Revenue (MR): This is the additional revenue gained from selling one more unit of the product. For a monopolistic competitor, the MR curve slopes downward because they have some control over the price and must lower the price to sell additional units.

- Marginal Cost (MC): This is the cost of producing one additional unit of the product. The MC curve typically slopes upward, indicating increasing costs as production increases.

- Profit Maximizing Output (Q): The profit-maximizing level of output is found where the MR and MC curves intersect. This point determines the quantity of goods the firm should produce to maximize profit. Or you may write this condition as MR=MC

- Price Determination: Once the profit-maximizing quantity is identified, the firm looks up to the demand curve to determine the highest price it can charge for that quantity. The demand curve shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded.

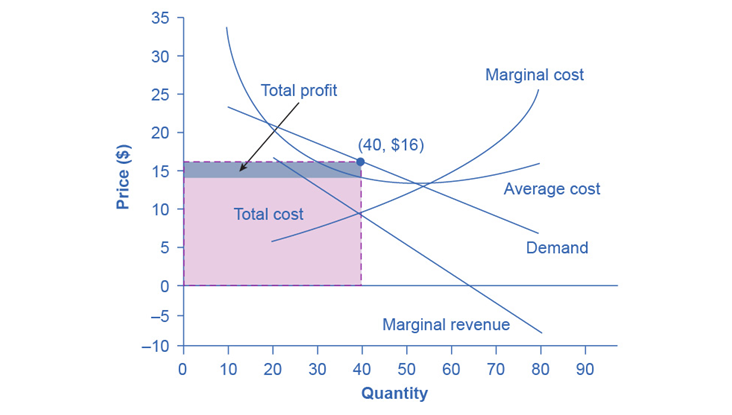

Graphical Representation

Let’s analyze the concept with the help of the following diagram from our reference book. You can see how a monopolistic competitor determines its pricing and quantity:

Axes and Curves:

- Y-Axis (Price $): Represents the price level in dollars.

- X-Axis (Quantity): Represents the quantity of output.

- Demand Curve: Shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded.

- Marginal Revenue (MR) Curve: Lies below the demand curve because the firm must lower prices to sell additional units.

- Marginal Cost (MC) Curve: Typically upward-sloping, indicating increasing costs with increased production.

- Average Cost (AC) Curve: Shows the average cost of production at different levels of output.

Key Points and Areas:

- Intersection Point (40, $16): The point where the MR and MC curves intersect. This indicates the profit-maximizing quantity (Q=40 Units) and the corresponding price ($16).

- Total Profit Area: The shaded area above the AC curve and below the price level at the profit-maximizing quantity represents total profit.

- Total Cost Area: The shaded area below the AC curve and up to the profit-maximizing quantity represents total cost.

Numerical Explanation for a Monopolist

| Quantity | Price | Total Revenue | Marginal Revenue | Total Cost | Marginal Cost | Average Cost |

| 10 | $23 | $230 | $23 | $340 | $34 | $34 |

| 20 | $20 | $400 | $17 | $400 | $6 | $20 |

| 30 | $18 | $540 | $14 | $480 | $8 | $16 |

| 40 | $16 | $640 | $10 | $580 | $10 | $14.50 |

| 50 | $14 | $700 | $6 | $700 | $12 | $14 |

| 60 | $12 | $720 | $2 | $840 | $14 | $14 |

| 70 | $10 | $700 | -$2 | $1,020 | $18 | $14.57 |

| 80 | $8 | $640 | -$6 | $1,280 | $26 | $16 |

This example demonstrates how a monopolistic competitor determines its price and quantity to maximize profit by setting MR equal to MC and using the demand curve to set the corresponding price. The graph visually represents these concepts, highlighting the intersection points and relevant areas for total cost and revenue.

Entry and Exit in Monopolistic Competition

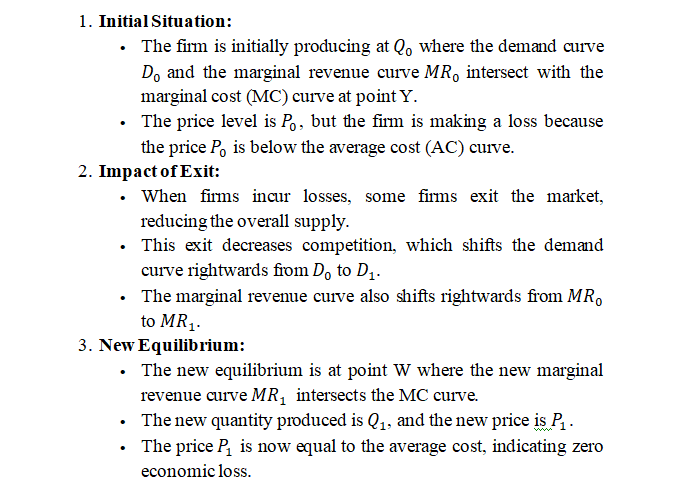

1. Entry of the Firm in Monopolistic Competition

When existing firms in a monopolistic competitive market are making profits, this attracts new firms to enter the market. These new firms see an opportunity to earn profits by differentiating their products and attracting some of the customers from the existing firms. This process of entry continues until the economic profits of the firms in the market are driven to zero.

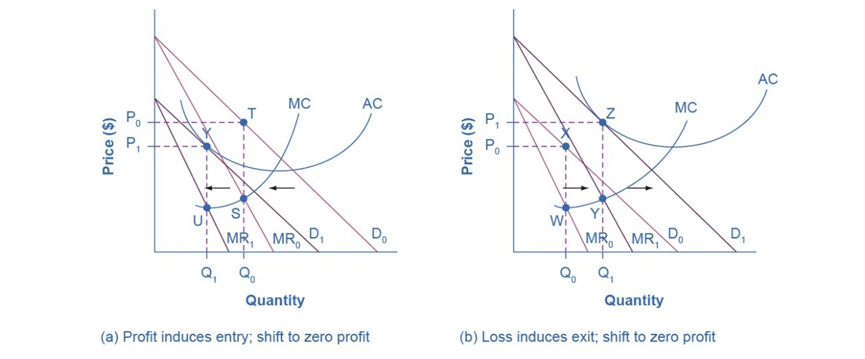

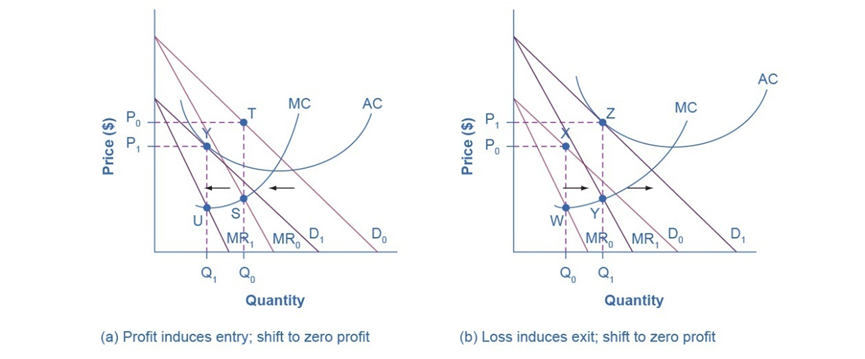

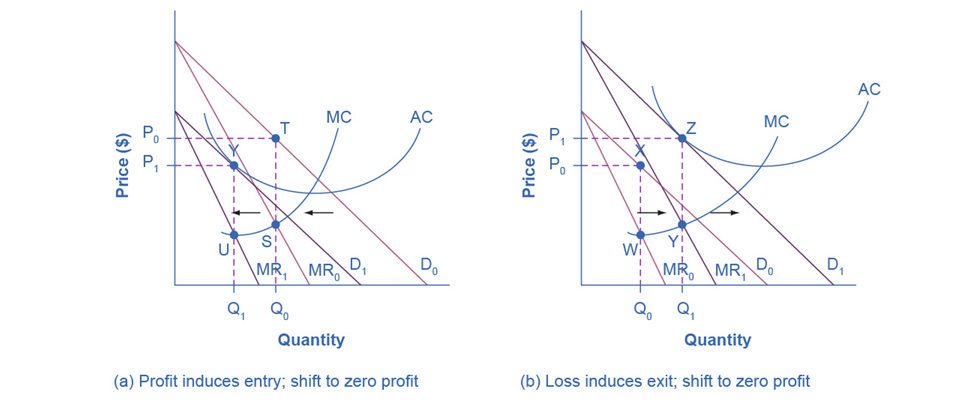

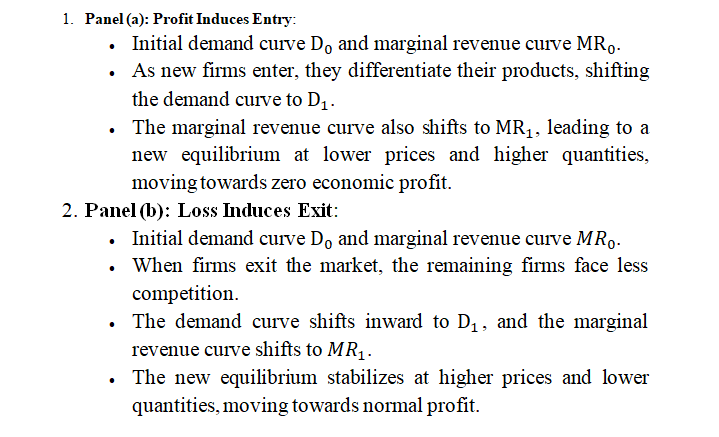

Graphical Representation for Entry

2. Exit of the Firm under Monopolistic Competition

When firms in a monopolistic competitive market incur losses, some firms will exit the market. The exit of firms reduces the overall competition, allowing the remaining firms to capture a larger market share and eventually return to a situation of normal profits (zero economic profit).

Graphical Representation for Exit

This entry and exit mechanism in monopolistic competition ensures that in the long run, firms will make zero economic profit, stabilizing the market. The diagrams clearly illustrate the shifts in demand and marginal revenue curves as firms enter or exit the market, leading to changes in output and price levels.

Efficiency in Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistic competition is not as efficient as perfect competition. This inefficiency arises due to two main reasons: allocative inefficiency and productive inefficiency.

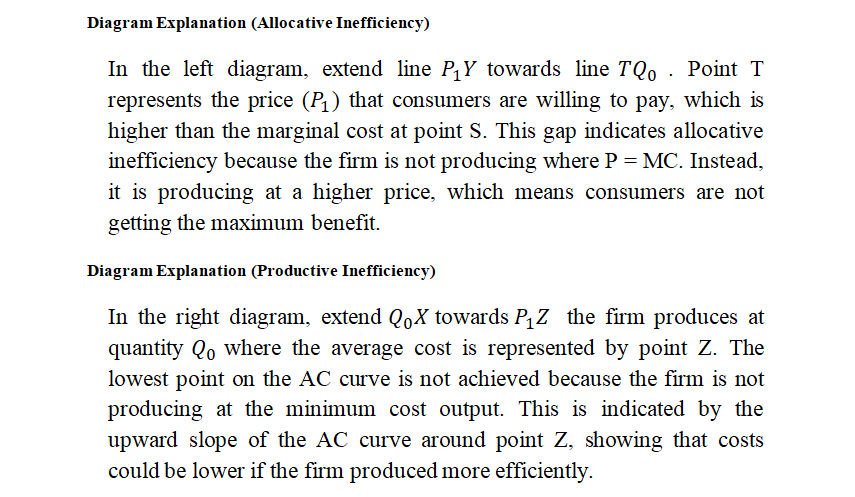

Allocative Inefficiency

Allocative inefficiency occurs when the price of a product is higher than the marginal cost of production. In an efficient market, the price should equal the marginal cost (P = MC), ensuring that resources are allocated in the most efficient way. However, in monopolistic competition:

- Firms have some degree of market power due to product differentiation, which allows them to set prices above marginal cost.

- The result is that consumers pay a higher price than the cost of producing an additional unit of the product, leading to a loss of allocative efficiency.

Productive Inefficiency

Productive inefficiency occurs when firms do not produce at the lowest point on their average cost (AC) curves. In perfect competition, firms produce at the minimum average cost in the long run. However, in monopolistic competition:

- Firms face downward-sloping demand curves, which means they produce less than the output that would minimize average cost.

- As a result, firms operate with excess capacity and higher average costs compared to a perfectly competitive firm.

Graphical Representation

This concept can be illustrated with the following diagram 12.2, which we discussed in the previous section:

- The average cost curve (AC) and the marginal cost curve (MC) are U-shaped.

- The firm produces quantity Q where MR = MC.

- However, the lowest point on the AC curve is at a higher quantity Qmin.

The gap between the current production level Q and the minimum cost production level Qmin represents productive inefficiency. The firm is not taking full advantage of economies of scale, resulting in higher average costs.

Diagram Explanation

Summary

In summary, monopolistic competition leads to higher prices and excess capacity, making it less efficient than perfect competition. These inefficiencies are visually represented by the differences between the price and marginal cost, as well as the gap between the actual output and the output that minimizes average cost.

Shifts in Perceived Demand and Marginal Revenue

Perceived Demand Shifts

In monopolistic competition, firms face a downward-sloping demand curve because of product differentiation. The perceived demand curve can shift due to various factors such as changes in consumer preferences, the entry of new firms, or changes in the overall market environment.

Relationship between Demand and Marginal Revenue

Derivation of MR from Demand:

The marginal revenue curve is derived from the demand curve. For any given price-quantity combination on the demand curve, the MR curve shows the extra revenue from selling one more unit.

Impact of Demand Shifts:

When the demand curve shifts, it changes the price-quantity combinations available to the firm.

An outward shift in demand (increase) typically means the firm can sell more at a higher price, which raises the marginal revenue at each quantity level.

Conversely, an inward shift in demand (decrease) means the firm sells less at each price, lowering the marginal revenue at each quantity level.

Factors Shifting Demand Curves

Changes in Consumer Preferences:

- If consumers develop a stronger preference for a firm’s product, the demand curve for that product shifts to the right (outward).

- Conversely, if consumers’ preferences shift away, the demand curve shifts to the left (inward).

Entry of New Firm

- When new firms enter the market with similar products, the perceived demand curve for existing firms shifts to the left due to increased competition.

- The marginal revenue curve also shifts leftward as a result.

Marketing and Advertising:

- Successful advertising can increase consumer demand, shifting the demand curve to the right.

- Ineffective advertising or negative publicity can shift the demand curve to the left.

Changes in Income:

- An increase in consumer income can shift the demand curve to the right for normal goods.

- A decrease in income can shift it to the left.

Impact on Pricing and Output Decisions

When the perceived demand curve shifts, it directly impacts the firm’s marginal revenue (MR) curve. Since the MR curve lies below the demand curve, any shift in demand results in a corresponding shift in MR. This affects the firm’s optimal pricing and output decisions:

- Outward Shift: An outward shift in the demand curve increases the price and quantity the firm can sell at profit-maximizing levels.

- Inward Shift: An inward shift decreases the price and quantity at profit-maximizing levels.

Stability of New Equilibrium

When the demand curve shifts, the market reaches a new equilibrium as firms adjust their prices and output levels. This process involves:

- Adjustment in Price and Output: Firms alter their pricing and output decisions based on the new demand and MR curves.

- Entry or Exit of Firms:

- If firms are making economic profits, new firms enter the market, shifting the demand curve left until economic profits are zero.

- If firms are incurring losses, some exit the market, shifting the demand curve right until normal profits are restored.

Graphical Representation with Figure 12.2

Diagram (a): Profit Induces Entry

Diagram (b): Loss Induces Exit

World Around Us: Shifts in Demand Curves

Case Study 1: Fast Food Industry

- Consumer Preferences:

The fast-food industry often sees shifts due to changing health trends. For instance, a growing preference for healthier options has led to increased demand for salads and grilled items over fried foods.

- Entry of New Firms:

New entrants like healthier fast-casual chains (e.g., Sweetgreen) have shifted demand curves for traditional fast-food giants like McDonald’s.

Example: McDonald’s

- Outward Shift:

When McDonald’s introduced healthier menu options and all-day breakfast, it saw an increase in customer demand. This shifted its demand curve outward, allowing it to charge higher prices and sell more.

- Inward Shift:

The entry of new competitors offering healthier and often locally sourced options led to a shift in the demand curve for McDonald’s inward, reducing its market share.

Market Dynamics

The fast-food industry is a prime example of how shifts in perceived demand and marginal revenue play out in real time:

- Introduction of New Products: Constant innovation in menus to cater to changing consumer tastes.

- Advertising Campaigns: Significant investment in marketing to influence consumer preferences.

- Competition: Entry and exit of firms impacting the competitive landscape and overall market equilibrium.

Case Study 2: Release of a new iPhone

Consider the smartphone market.

- Outward Movement of Perceived Demand:

- When Apple releases a new iPhone with innovative features, the demand for iPhone typically increases.

- The demand curve shifts outward due to increased consumer interest and preference for the new model.

- This leads to higher prices and quantities sold initially.

- Inward Movement of Perceived Demand:

- However, when other companies like Samsung or Google release competitive smartphones, the demand for the iPhone might decrease.

- The perceived demand curve for the iPhone shifts inward due to increased competition.

- Apple may have to lower prices or adjust its output to find a new equilibrium.

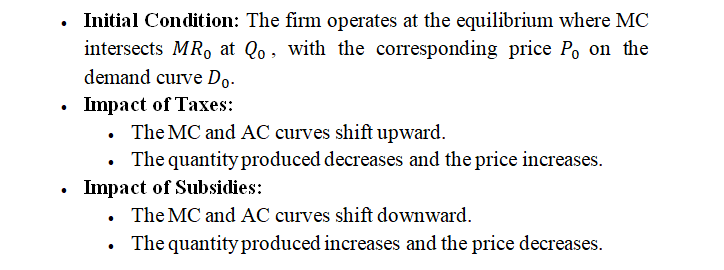

Shifts in Cost and Revenue Curves with Taxes and Subsidies

The diagram illustrates how changes in costs and demand impact a firm’s output and pricing decisions in a monopolistic competition market. Let’s understand how taxes and subsidies affect the cost and revenue curves.

1. Taxes

Impact on Cost Curves:

- Imposition of Taxes:

- When a tax is imposed, it increases the firm’s costs. This could be a per-unit tax or a fixed tax.

- A per-unit tax increases the marginal cost (MC) and the average cost (AC) curves upward by the amount of the tax.

- This is represented in the diagram by a shift of the MC and AC curves upward.

Impact on Revenue Curves:

- The demand and marginal revenue (MR) curves typically remain unchanged as taxes primarily affect costs.

- However, if the tax reduces consumer purchasing power significantly, it might indirectly lower the perceived demand.

Result of Tax Imposition:

Higher costs reduce the quantity produced by the firm and increase the price charged to consumers, moving the equilibrium leftward on the quantity axis.

2. Subsidies

Impact on Cost Curves:

- Provision of Subsidies:

- A subsidy lowers the firm’s costs, either as a per-unit subsidy or a fixed amount.

- A per-unit subsidy decreases the MC and AC curves downward by the amount of the subsidy.

- This is represented in the diagram by a shift of the MC and AC curves downward.

Impact on Revenue Curves:

The demand and MR curves usually remain unchanged. However, if the subsidy boosts consumer purchasing power, it might indirectly increase perceived demand.

Result of Subsidies:

Lower costs increase the quantity produced by the firm and decrease the price charged to consumers, moving the equilibrium rightward on the quantity axis.

Graphical Representation

Let’s apply this understanding to the provided diagram:

Figure 12.2 Shifts due to Taxes and Subsidies

(a) Profit Induces Entry; Shift to Zero Profit

(b) Loss Induces Exit; Shift to Zero Profit

Summary

- Taxes increase production costs, shifting the MC and AC curves upward, reducing output, and increasing prices.

- Subsidies decrease production costs, shifting the MC and AC curves downward, increasing output, and reducing prices.

In real-world cases, governments use taxes and subsidies to influence market outcomes, balancing efficiency and equity objectives. For example, environmental taxes aim to reduce pollution, while agricultural subsidies support farm incomes and stabilize food prices.

The advantages of Product Differentiation in Monopolistic Competition

In monopolistic competition, firms differentiate their products to attract consumers. This differentiation creates variety in the market, benefiting consumers by providing more choices and catering to different preferences and needs.

Concept Explanation

Product Differentiation:

- Firms offer products that are distinct in terms of quality, features, branding, or style.

- This allows consumers to choose products that best meet their preferences.

- Differentiation can lead to customer loyalty and the ability to charge a premium price.

Consumer Benefits:

- Variety: Consumers enjoy a range of products, enhancing their satisfaction.

- Better Match to Preferences: Consumers can find products that closely match their tastes and needs.

- Innovation: Competition encourages firms to innovate, leading to new and improved products.

Firm Benefits:

- Market Power: Differentiation gives firms some degree of market power, allowing them to set prices above marginal cost.

- Customer Loyalty: Unique products can build brand loyalty, reducing the sensitivity to price changes.

- Flexibility in Pricing: Firms can adjust prices without losing all their customers, unlike in perfect competition.

Graphical Representation

The provided diagram (a and b) can illustrate the concept of product differentiation and its impact on demand and revenue:

In both scenarios, the variety and differentiation of products are reflected in the shifts of the demand and marginal revenue curves. Firms entering the market introduce new variations, shifting demand outwards, while firms exiting reduce the available variety, shifting demand inwards.

World around Us: Smartphone Market

The smartphone market is a prime example of product differentiation:

Apple vs. Samsung:

Apple differentiates with its iOS ecosystem, design, and brand image.

Samsung differentiates with diverse models, Android features, and innovation in hardware.

Consumer Benefits:

Variety: Consumers can choose between high-end, mid-range, and budget smartphones.

Preferences: Options cater to different operating systems, camera quality, battery life, etc.

Market Dynamics:

Entry: New brands like Xiaomi enter the market with differentiated products, increasing competition and variety.

Exit: Brands like HTC and LG reduce their presence, leading to a shift in market equilibrium.

The shifts in perceived demand and marginal revenue due to product differentiation and market entries/exits highlight the dynamic nature of monopolistic competition and its benefits to both consumers and firms.

References

- Mankiw, N. G. (2020). Principles of Economics. Cengage Learning.

- Pindyck, R. S., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (2018). Microeconomics. Pearson Education.

- Case Study: Smartphone Market Trends

This detailed explanation covers the concept, diagram interpretation, and a real-world example, providing a comprehensive understanding of the benefits of variety and product differentiation in monopolistic competition.

Advertising in Monopolistic Competition

Advertising plays a crucial role in monopolistic competition by affecting both the perceived demand and marginal revenue curves. Here’s a detailed explanation of how advertising impacts firms in a monopolistically competitive market, using the provided diagram for illustration:

Impact of Advertising

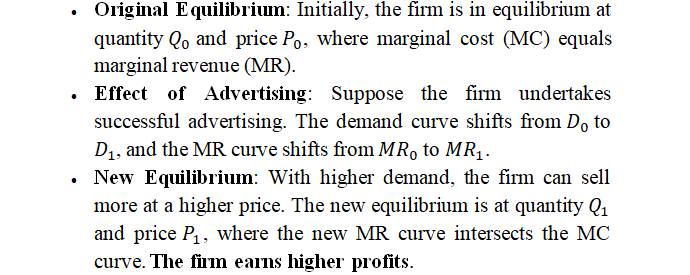

Shift in Perceived Demand (Demand Curve):

Increase in Demand: Effective advertising can increase consumers’ preference for a product, shifting the demand curve outward (to the right). This shift indicates that at every price level, consumers are willing to buy more of the product.

Decrease in Demand: Conversely, if advertising fails or negative publicity occurs, the demand curve may shift inward (to the left), indicating that consumers are less willing to buy the product at every price level.

Shift in Marginal Revenue (MR Curve):

As the demand curve shifts due to advertising, the marginal revenue curve shifts in the same direction. This is because marginal revenue is derived from the demand curve. An outward shift in the demand curve results in an outward shift in the MR curve, and an inward shift in the demand curve results in an inward shift in the MR curve.

Graphical Representation

Panel (a): Profit Induces Entry; Shift to Zero Profit:

Panel (b): Loss Induces Exit; Shift to Zero Profit:

World Around Us: The Impact of Advertising on Coca-Cola and Pepsi

Advertising has played a pivotal role in shaping the competition between Coca-Cola and Pepsi, two of the most well-known brands in the world. Here’s a detailed look at how advertising has affected their demand, with facts and figures to illustrate the impact:

Coca-Cola

Campaigns and Strategies:

“Share a Coke” Campaign: This campaign allowed customers to personalize Coca-Cola bottles with their names or the names of loved ones. It created a personal connection with the brand, resulting in a significant boost in sales and engagement. The campaign reportedly gained over 25 million new Facebook followers for Coca-Cola (Kimp).

Emotional Marketing: Coca-Cola often leverages emotions such as happiness and nostalgia. Their Christmas ads featuring Santa Claus are iconic and have become synonymous with the festive season (Kimp).

Endorsements and Sponsorships: Coca-Cola has long-standing partnerships with major sports events like the Olympic Games, which help to reinforce its global brand presence and connect with diverse audiences (Kimp).

Impact on Demand:

Increased Sales: Campaigns like “Share a Coke” not only increased direct sales but also enhanced brand loyalty and customer engagement.

Brand Recognition: Coca-Cola’s consistent use of red and its focus on happiness and togetherness have made it a globally recognized brand, helping to maintain high demand (Kimp).

Pepsi

Campaigns and Strategies:

Pepsi Challenge: This blind taste test campaign in the 1980s challenged consumers to choose between Pepsi and Coca-Cola without knowing which was which. It successfully positioned Pepsi as a youthful and bold alternative to Coca-Cola (HackerNoon) (Kimp).

Celebrity Endorsements: Pepsi has used endorsements from celebrities like Michael Jackson and Britney Spears to appeal to younger audiences. These endorsements have helped Pepsi maintain a trendy and modern image (HackerNoon).

Humorous Advertising: Pepsi often uses humor in its ads, which resonates well with its target audience. This approach contrasts with Coca-Cola’s more emotional marketing and helps Pepsi stand out (Kimp).

Impact on Demand:

- Market Share: The Pepsi Challenge and similar campaigns have helped Pepsi gain significant market share, particularly among younger consumers.

- Brand Image: By continuously updating its logo and embracing modern marketing trends, Pepsi has maintained a dynamic and adaptable brand image, which helps keep demand strong among its core demographics (Kimp).

Comparative Analysis

Similarities:

- Both brands invest heavily in advertising and endorsements.

- Both leverage emotional marketing but in different ways: Coca-Cola focuses on happiness and nostalgia, while Pepsi uses humor and boldness.

- Both have adapted to changing consumer preferences by introducing healthier options and marketing these products effectively (Kimp).

Differences:

- Emotional vs. Humorous Marketing: Coca-Cola’s ads evoke feelings of warmth and connection, while Pepsi’s ads often use humor and direct competition.

- Brand Positioning: Coca-Cola positions itself as a timeless classic, while Pepsi markets itself as a youthful and modern alternative (Kimp) (HackerNoon).

Summary

The advertising strategies of Coca-Cola and Pepsi have significantly influenced their market positions and consumer demand. Coca-Cola’s focus on emotional connection and tradition has helped it maintain a strong global presence. In contrast, Pepsi’s use of humor and adaptability has enabled it to capture a younger audience and remain competitive. Both approaches have proven effective in different ways, showcasing the power of tailored advertising strategies in monopolistic competition.

Positive and Negative Impacts of Advertising in Monopolistic Competition

Positive Impacts:

- Increases Consumer Awareness:

- Advertising helps consumers become aware of the product’s existence, features, and benefits. This awareness can lead to an increase in demand.

- Example: Coca-Cola’s “Share a Coke” campaign increased consumer awareness by personalizing the product, resulting in higher sales and brand engagement.

- Increased Sales and Profits:

- Effective advertising can lead to higher sales volumes as consumers are more likely to purchase products they are familiar with and trust.

- Example: Pepsi’s use of celebrity endorsements has often resulted in short-term sales boosts and long-term brand loyalty among fans of those celebrities.

Negative Impacts:

- High Advertising Costs:

- The cost of advertising can be substantial. These costs are often passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

- Example: Both Coca-Cola and Pepsi spend millions annually on advertising. These expenses can lead to higher prices for their products to maintain profit margins.

- Barriers to Entry for New Firms:

- High advertising expenditures by established firms create a barrier to entry for new competitors who may not have the financial resources to compete on the same level.

- Example: New beverage companies may find it difficult to gain market share against Coca-Cola and Pepsi due to the latter’s massive advertising budgets and established brand loyalty.

Summary

Advertising in monopolistic competition can significantly influence a firm’s demand and marginal revenue, affecting its pricing and output decisions. The provided diagram effectively illustrates how changes in perceived demand, driven by advertising, impact the firm’s equilibrium and profitability.

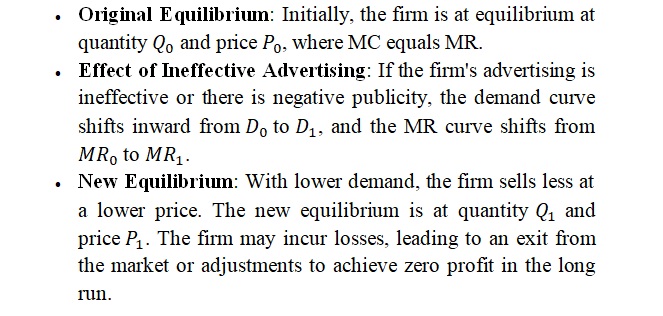

Differences, Similarities, and Comparison between Perfect Competition and Monopolistic Competition

Differences

| Feature | Perfect Competition | Firms have some control over the price |

| Number of Firms | Many firms | Many firms |

| Product Differentiation | Homogeneous products | Differentiated products |

| Barriers to Entry | No barriers to entry | Low barriers to entry |

| Market Power | Firms are price takers | Firms are price-takers |

| Demand Curve | Perfectly elastic (horizontal) | Downward sloping |

| Price Maker/Taker | Price taker | Price maker within a range |

| Long-Run Profits | Zero economic profit in the long run | Zero economic profit in the long run due to entry/exit |

| Advertising | Not necessary | Significant use of advertising |

| Efficiency | Allocative and productive efficiency | Neither allocative nor productive efficiency |

Similarities

| Feature | Perfect Competition | Monopolistic Competition |

| Number of Firms | Many firms | Many firms |

| Free Entry/Exit | Yes | Yes |

| Short-Run Profits | Can earn economic profits or incur losses | Can earn economic profits or incur losses |

| Profit Maximization | Both maximize profit where MR = MC | Both maximize profit where MR = MC |

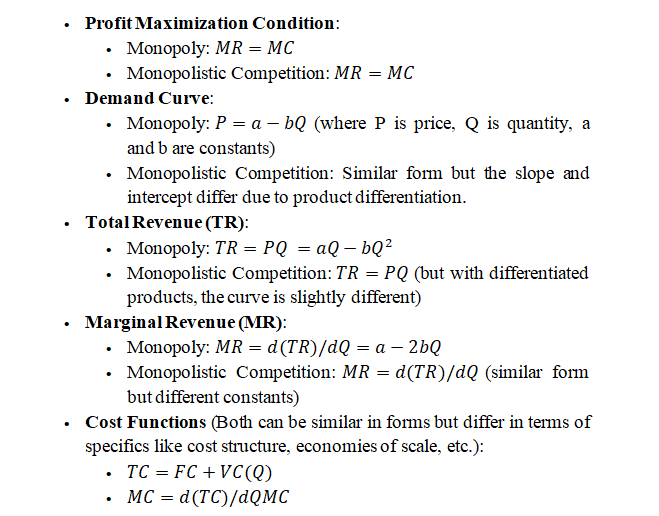

Equations for Comparison

Summary

Both perfect competition and monopolistic competition involve many firms and free entry/exit, yet they differ significantly in terms of product differentiation and market power. Perfect competition features homogeneous products and firms as price takers, leading to allocative and productive efficiency. Monopolistic competition features differentiated products, allowing firms some control over prices, but resulting in neither allocative nor productive efficiency. In the long run, both market structures see firms earning zero economic profit due to the entry and exit of firms.

Differences, Similarities, and Comparison between Monopoly and Monopolistic Competition

Differences

| Feature | Monopoly | Monopolistic Competition |

| Number of Firms | Single firm | Many firms |

| Product Differentiation | No close substitutes | Differentiated products |

| Barriers to Entry | High barriers to entry | Low barriers to entry |

| Market Power | Significant control over price | Some control over price |

| Demand Curve | Downward sloping | Downward sloping |

| Price Maker/Taker | Price maker | Price maker within a range |

| Long-Run Profits | Can earn long-run economic profits | Zero economic profit in the long run due to entry/exit |

Similarities

| Feature | Monopoly | Monopolistic Competition |

| Profit Maximization | It maximizes profit where MR = MC | It also maximizes profit where MR = MC |

| Downward Sloping Demand Curve | It faces a downward-sloping demand curve | It also faces a downward-sloping demand curve |

| Non-Price Competition | May engage in advertising and other non-price competition | Significant use of advertising and branding techniques. |

| Price Maker | Both have some degree of price-setting power | Both have some degree of price-setting power |

Equations for Comparison

Summary

While monopolies and monopolistic competition have distinct characteristics, they share some similarities in their market behaviors and pricing strategies. The key differences lie in the number of firms, product differentiation, and long-term profit potential. Understanding these distinctions helps in analyzing market dynamics and the strategic behavior of firms in different market structures.

Monopolistic Competition and Behavioral Economics

In monopolistic competition, firms sell similar but differentiated products. They have some degree of market power to set prices above marginal costs. Behavioral economics shows that consumer preferences and cognitive biases can influence decision-making, leading firms to use strategies like advertising and branding to exploit these biases.

Scenario: The Smartphone Market

Consider the smartphone market, where companies like Apple, Samsung, and Huawei operate in a monopolistic competition environment. They sell differentiated products through branding, design, and features.

Cognitive Biases

- Anchoring Bias: Consumers might anchor their perception of a smartphone’s value based on previous models. For example, Apple uses high prices for older iPhone models to make new models appear relatively cheaper, even when the price difference isn’t large.

- Confirmation Bias: Brand-loyal customers might seek information that confirms their belief that their preferred brand is superior, ignoring any negative reviews or flaws in the product. This reinforces their purchase decisions even when cheaper and equally good alternatives exist.

Prospect Theory and Loss Aversion

- Loss Aversion: Smartphone companies exploit loss aversion by emphasizing what consumers would miss out on if they don’t buy the latest model. For instance, Samsung may highlight the risk of missing out on advanced camera features, making consumers reluctant to stick with older models.

- Framing Effect: Companies use the framing effect to influence decisions. Apple might frame the choice of upgrading as an opportunity for consumers to stay ahead in technology, even when the actual improvements in performance might be marginal.

World Around Us: Smart Phone

A study of the smartphone market revealed that when Apple introduced the iPhone X in 2017 with a price 30% higher than previous models, sales did not drop as expected. Instead, they remained stable, and the company’s profits surged by 20% . This suggests that branding, combined with loss aversion and anchoring, helped Apple maintain high sales despite price increases.

Impact and Analysis

In monopolistic competition, firms capitalize on behavioral biases like anchoring and loss aversion to maintain higher prices and market power. This behavior is evident in industries like smartphones, where companies use branding and subtle psychological strategies to influence consumer decisions.

References

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk.

- Apple’s iPhone X Pricing Study, 2017

- Investopedia: Perfect Competition

- Investopedia: Monopolistic Competition

This case study of monopolistic competition illustrates how firms exploit behavioral biases like loss aversion and anchoring to sustain higher prices, even when product differentiation is minimal. The role of behavioral economics provides crucial insights into the strategic decisions of firms in such markets.

Research Suggestions in Behavioral Economics

1. Behavioral Pricing Strategies in Monopolistic Competition

Study how firms in monopolistic competition use behavioral pricing strategies to exploit consumer biases, and how these strategies affect long-term market dynamics.

2. Impact of Nudging on Brand Loyalty

Explore how nudging consumers towards more rational decisions (e.g., through transparent product comparisons) can reduce brand loyalty and encourage competition in monopolistic markets.

3. The Role of Loss Aversion in Product Differentiation

Investigate how firms design their marketing strategies to exploit loss aversion and whether this leads to more differentiated products or just perceived differences.

4. Cognitive Biases and Market Efficiency

Examine the impact of cognitive biases on market efficiency in monopolistic competition, particularly how firms maintain price power without substantial product differences.

Critical Thinking

- How does product differentiation in monopolistic competition impact consumer choice and market efficiency?

- What are the potential benefits and drawbacks of product differentiation for both consumers and producers?

- In what ways does advertising influence the demand curve in a monopolistic competitive market?

- How can excessive advertising lead to market inefficiencies?

- Why do firms in monopolistic competition earn zero economic profit in the long run?

- How does the concept of free entry and exit of firms lead to zero economic profit in the long run?

- How do firms in monopolistic competition exert some control over prices, despite the presence of many competitors?

- Compare the price-setting behavior of firms in monopolistic competition to those in perfect competition.

- Why are neither allocative nor productive efficiencies achieved in monopolistic competition?

- How do the inefficiencies in monopolistic competition compare to those in monopoly and perfect competition?

- How does the entry of new firms affect the demand curve and economic profits of existing firms in a monopolistically competitive market?

- What role does consumer loyalty play in sustaining economic profits for firms in the short run?

Numericals