Today, we will discover the fascinating theory of consumption and how consumers make choices. We’ll discuss how changes in income and prices affect these choices, why consumer behavior might not always be rational, and how to make decisions that maximize utility. We have discussed some of these concepts earlier during “Lecture 2: Choices in the World of Scarcity.” You should brainstorm those ideas before starting this lecture. We will recall some ideas again for continuity and then discuss the indifference curves in detail.

Consumption Choices

Consumption choices refer to the decisions consumers make regarding the purchase of goods and services. Several factors including income, prices, preferences, and external economic conditions influence these choices.

Factors Influencing Consumption Choices

- Income Levels: The amount of money a consumer earns determines their purchasing power.

- Prices of Goods and Services: Consumers consider the cost of items and make choices based on affordability.

- Preferences and Tastes: Personal likes, cultural influences, and trends play a significant role in consumption choices.

- External Economic Conditions: Inflation, employment rates, and economic policies can also affect consumer behavior.

World Around Us: Consumption Choices

Consider how you decide what to buy for lunch. Your choice depends on your budget (income), the prices of available food items, and your personal preferences. For instance, you might choose a local dish because it’s cheaper and you enjoy it more than an international meal.

Case Study: Consumption Choices and Mobile Phone Market in India (2016-2020)

The mobile phone market in India has seen dramatic shifts due to changes in consumer preferences and income levels, particularly from 2016 to 2020.

Impact on Consumption Choices:

Rising Income Levels:

Between 2016 and 2020, India’s per capita income increased by around 6-7% annually.

In 2016, per capita income was approximately INR 1,03,870, which rose to about INR 1,34,226 by 2020.

Higher disposable income led to increased spending on technology and mobile phones.

Price Sensitivity and Demand:

The launch of affordable smartphones by companies like Xiaomi, Oppo, and Vivo significantly impacted consumer choices.

Consumers shifted from basic phones to smartphones, with budget segments (under INR 15,000) seeing the highest growth.

Technological Advancements:

Introduction of 4G technology and subsequent data plans at affordable rates by companies like Reliance Jio.

Data consumption per user increased from 0.3 GB per month in 2016 to 9.8 GB per month in 2020.

Enhanced data services and cheaper internet plans led to a higher demand for smartphones.

Economic Data:

Market Growth: The smartphone market in India grew by approximately 11% year-on-year during this period.

Market Share: Companies like Xiaomi captured around 30% of the market share by 2020, largely due to their competitive pricing and quality.

Government Initiatives:

Digital India Campaign: Encouraged digital literacy and boosted mobile phone penetration.

Subsidies and Policies: Various policies aimed at making smartphones affordable for the masses, further driving demand.

Summary:

The Indian mobile phone market from 2016 to 2020 provides us a clear example of how rising incomes, technological advancements, and government initiatives can significantly influence consumer choices. Understanding these factors helps in analyzing how similar trends might play out in other developing economies.

In-Depth Analysis

When we talk about consumption choices, we delve into understanding how individuals make decisions to allocate their limited resources among various goods and services to maximize their satisfaction. This involves analyzing how different factors such as changes in income or prices can shift these choices.

a. Budget Constraint Graph

It shows the combinations of goods a consumer can buy with a fixed budget. Consult lecture 2 for further details.

Axis: One axis represents the quantity of good X, and the other represents the quantity of good Y.

Budget Line: Represents all possible combinations of X and Y that a consumer can afford.

Impact of Income Change: A higher income shifts the budget line outward.

b. Indifference Curves

It represents different combinations of goods that provide the same level of satisfaction to a consumer.

Axis: Similar to the budget constraint graph.

Curves: Each curve represents a different level of utility.

Optimal Consumption Point: The point where the budget line is tangent to an indifference curve represents the optimal consumption choice.

Measuring Utility with Different Approaches

- Understanding Utility: Total Utility, Marginal Utility, and Maximizing Utility

- Utility with Numbers

- Indifference Curve

1. Understanding Utility: Total Utility, Marginal Utility, and Maximizing Utility

These concepts are crucial for understanding consumer behavior in economics. We will also explore these ideas through a real-world case study.

Total Utility

Total Utility (TU) is the overall satisfaction or pleasure a consumer derives from consuming a certain quantity of goods or services.

Example: If you consume 3 apples, the total utility is the combined satisfaction from all 3 apples.

Calculation: To calculate total utility, sum up the utility derived from each unit consumed.

TU=∑MU

MU=Marginal Utility

Marginal Utility

Marginal Utility (MU) is the additional satisfaction or utility gained from consuming one more unit of a good or service.

Example: If the first apple gives you 10 units of satisfaction and the second gives you 8 units, the marginal utility of the second apple is 8.

Diminishing Marginal Utility

As you consume more units of a good, the additional satisfaction (marginal utility) typically decreases.

Example: The first slice of pizza is very satisfying, but by the fourth or fifth slice, the additional satisfaction is much less.

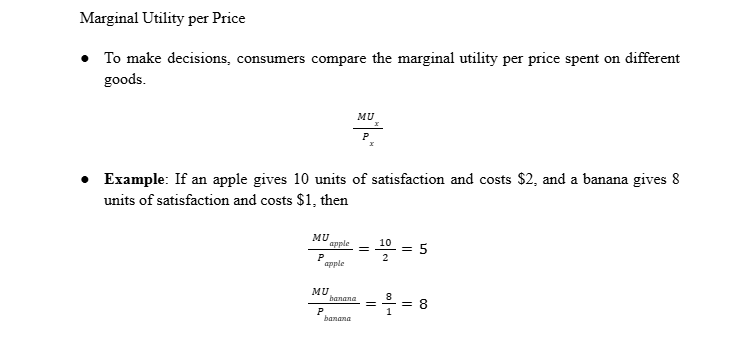

Choosing with Marginal Utility

The Rule of Maximizing Utility

Measuring Utility with Numbers

Utility is often measured in hypothetical units called “utils.” If the first apple gives 10 utils, the second 8 utils, and the third 6 utils, the total utility for 3 apples is 10+8+6=24 utils.

Graphical Representation

Figure 7.1: A Choice Between Consumption Goods with Budget Constraints

José has $56 to spend on T-shirts ($14 each) and movies ($7 each). His budget constraint line shows possible combinations: 0 T-shirts and 8 movies, or 4 T-shirts and 0 movies. He aims to maximize utility, measured in utils. Total utility increases with consumption, but marginal utility diminishes. José calculates marginal utility per dollar to decide optimal spending. He achieves the highest total utility at one T-shirt and six movies, following the rule where marginal utility per dollar is equal for both goods.

Case Study: The Coffee Market in Brazil

Brazil is the largest producer and exporter of coffee in the world. The dynamics of the coffee market provide an insightful case study for understanding total utility, marginal utility, and consumer choices.

Facts & Figures

- Brazil produces approximately 37% of the world’s coffee. In 2020, Brazil produced around 3.55 million metric tons of coffee.

- Coffee prices fluctuate due to changes in production, global demand, and market speculation. The price of coffee can vary significantly, impacting consumer choices both domestically and internationally.

- Total Utility:

Brazilian consumers derive significant total utility from coffee consumption due to cultural and habitual factors. For many, coffee is an essential part of daily life, providing energy and pleasure.

A consumer who drinks 3 cups of coffee a day may derive a total utility of 50 utils from his daily consumption.

- Marginal Utility:

The first cup of coffee in the morning provides the highest marginal utility; say 30 utils, due to the high level of satisfaction and energy boost.

The second cup might provide 15 utils, and the third cup, only 5 utils, illustrating diminishing marginal utility.

Marginal utility decreases with each additional cup consumed.

- Choosing with Marginal Utility:

Consumers choose to purchase coffee up to the point where the marginal utility per dollar spent is maximized.

If a cup of coffee costs $1 and the first cup provides 30 utils, the marginal utility per dollar is 30. For the second cup providing 15 utils, it is 15 utils per dollar, and so on.

- Rule of Maximizing Utility:

Consumers will allocate their spending to equalize the marginal utility per dollar across all goods.

If tea provides 20 utils per dollar and coffee provides 15 utils per dollar, consumers might choose tea over coffee unless their preferences or circumstances change.

Price Increase Impact

In 2021, adverse weather conditions and supply chain disruptions caused a spike in coffee prices.

Before the Price Increase: A cup of coffee costs $1, with consumers purchasing 3 cups daily.

After the Price Increase: The price rose to $1.50 per cup.

Total Utility Before: 3 cups x 50 utils = 150 utils

Total Utility After: Consumers might reduce consumption to 2 cups due to higher prices, resulting in 2 cups x 45 utils = 90 utils.

Marginal Utility Analysis: The marginal utility per dollar changes, making consumers re-evaluate their spending on coffee versus other goods.

Measuring Utility with Numbers

Total Utility (TU): Coffee Cups per Week:

- 1 cup: 10 utils

- 2 cups: 18 utils

- 3 cups: 25 utils

- 4 cups: 31 utils

Marginal Utility (MU):

- 1st cup: 10 utils (10 TU – 0 TU)

- 2nd cup: 8 utils (18 TU – 10 TU)

- 3rd cup: 7 utils (25 TU – 18 TU)

- 4th cup: 6 utils (31 TU – 25 TU)

- Utility Maximization:

- Consumers decide how many cups of coffee to buy based on their budget and the price of coffee.

- They compare the marginal utility per dollar spent on coffee to other goods.

Hence measuring utility in numbers, consumers like coffee drinkers in Brazil can make informed decisions to maximize their satisfaction given their budget constraints. They look at both total utility and marginal utility to determine the best combination of goods to purchase.

Summary

This case study illustrates how changes in price affect total and marginal utility, and how consumers adjust their consumption choices to maximize their utility given their budget constraints. The coffee market in Brazil provides a practical example of these economic concepts in action.

2. Measuring Utility with Indifference Curves

Indifference curves provide a way to understand personal preferences without needing numbers to measure satisfaction. They show combinations of goods that give equal satisfaction.

Indifference curves slope downward and are convex (steeper on the left, flatter on the right).

We will continue with our reference book to make a clear understanding of it.

Figure 7.2 Indifference Curves and a Budget Constraint

Graph Setup:

X-axis: Books

Y-axis: Doughnuts

Three curves: Ul, Um, Uh

The convex shape reflects the trade-offs Lilly makes between books and doughnuts while maintaining the same level of satisfaction.

Lilly gets the same satisfaction from all points on one curve. Higher curves mean more satisfaction.

For Example: Points on Curve Um

- A (2 books, 120 doughnuts)

- B (3 books, 84 doughnuts)

- C (11 books, 40 doughnuts)

- D (12 books, 35 doughnuts)

Lilly’s satisfaction remains constant across these points.

Diminishing Marginal Utility

As Lilly consumes more of one good, the added satisfaction (marginal utility) from each extra unit decreases. For example, moving from point A to B, Lilly trades 36 doughnuts for 1 more book because the marginal utility of doughnuts is lower when she already has many. Conversely, moving from C to D, she trades only 5 doughnuts for 1 more book because the marginal utility of books is lower when she already has many.

Utility Maximization with Budget Constraints

Lilly aims to reach the highest possible indifference curve within her budget.

Example:

- Books: $6 each

- Doughnuts: $0.50 each

- Budget: $60

Lilly’s optimal choice is where her budget line touches an indifference curve, giving her maximum satisfaction.

Optimal Choice: Point B

B: 3 books, 84 doughnuts

This point is on the curve Um, which is the highest indifference curve she can afford.

Lilly can’t afford higher curves like Uh, but lower curves like curve Ul, providing less satisfaction.

Hence indifference curves offer a clear, non-numerical way to understand choices and preferences, showing how people balance different goods to achieve maximum satisfaction within their budget.

How Changes in Income and Prices Affect Consumption Choices

1. Income Effect

When income increases, consumers can afford to buy more goods and services. Conversely, when income decreases, consumers buy less.

Figure 7.3 How a Change in Income Affects Consumption Choices

Example: Kimberly’s Choices

- Budget: $1,000 for concert tickets ($50 each) and bed-and-breakfast stays ($200 per night).

- Initial choice: 8 concerts, 3 overnight stays (point M).

When her income increases to $2,000, the budget shifts. Kimberly’s new choices depend on whether goods are normal or inferior.

New Choices:

- Normal goods: More of both (point N).

- Inferior good: Less of one, more of the other (points P or Q).

Income increases usually lead to buying more of both goods (normal goods). However, if one good is inferior, its consumption might decrease as income rises.

Indifference Curves with Income Effects

Figure 7.4 Changes in Income and Consumer Behavior

When income increases, the budget line moves to the right, allowing consumers to reach higher indifference curves, which represent higher utility levels. Conversely, a decrease in income shifts the budget line left, touching lower indifference curves and indicating lower utility.

- Left Panel (Manuel’s Preferences):

- The original budget line intersects the y-axis at 40 yogurts and the x-axis at 10 movies.

- The highest indifference curve tangent to the original budget line touches at point W, showing Manuel’s initial choice of 3 movies and 28 yogurts.

- When income rises, the budget line shifts outward, and the new highest indifference curve touches at point X, showing Manuel’s new choice of 7 movies and 32 yogurts. Manuel increases his consumption of both goods, especially movies.

- Right Panel (Natasha’s Preferences):

- The original budget line is identical, but Natasha’s highest indifference curve touches theat point Y, showing her initial choice of 7 movies and 12 yogurts.

- With the income increase, the budget line shifts outward. The new highest indifference curve touches theat point Z, showing Natasha’s new choice of 8 movies and 28 yogurts. Natasha increases her consumption of both goods, but more significantly for yogurts.

This figure demonstrates that while both individuals increase their consumption when income rises, their preferences lead them to allocate their additional income differently. This illustrates how normal and inferior goods affect consumption choices under different budget constraints.

Normal Goods and Inferior Goods

| Normal Goods | Inferior Goods |

| Definition: Goods for which demand increases as income rises. | Definition: Goods for which demand decreases as income rises. |

| Examples: Fresh fruits, electronics, dining out. | Examples: Instant noodles, bus rides, used cars. |

| Behavior: When people earn more, they buy more of these goods because they can afford to improve their standard of living. | Behavior: As income increases, people buy less of these goods, opting for higher-quality alternatives. |

| Income Elasticity: Positive; a rise in income leads to a rise in quantity demanded. | Income Elasticity: Negative; a rise in income leads to a fall in quantity demanded. |

Key Points:

- Preference-Based: What is normal or inferior can vary between individuals.

- Impact on Budget: Income changes shift the budget line, affecting how much of each type of good is consumed.

- Utility Maximization: Consumers aim to maximize their satisfaction given their budget constraints, choosing more normal goods with higher income and fewer inferior goods.

- Consumption Patterns: Higher income typically leads to more consumption of normal goods. For inferior goods, consumption decreases as people switch to higher-quality alternatives.

How Price Changes Affect Consumer Choices

When prices change, it’s not just the consumption of the specific good that is affected, but potentially other goods as well. For Sergei, a higher price for baseball bats means he has less money to spend on other things, including cameras.

Figure 7.5 How a Change in Price Affects Consumption Choices

Figure 7.5 shows Sergei’s budget constraint for buying baseball bats and cameras.

Description:

- Axes: Cameras are on the y-axis, and baseball bats are on the x-axis.

- Budget Constraint: The original budget line is downward-sloping, showing the trade-off between the two goods.

- Price Increase: When the price of baseball bats rises, the budget line rotates inward from the vertical axis, reducing the number of bats Sergei can afford.

- Points:

- M: Original utility-maximizing point.

- H, J, K, and L: New consumption possibilities after the price increase.

- H: More cameras, fewer bats.

- J: Less of both goods.

- K: Same number of bats, fewer cameras.

- L: More bats, fewer cameras (unlikely in real life).

- Substitution Effect: If baseball bats become more expensive, Sergei might buy fewer bats and more cameras, switching to the relatively cheaper option.

- Income Effect: Higher bat prices reduce Sergei’s effective income, possibly leading to reduced consumption of both goods.

Indifference Curves Responses to Price Changes: Substitution and Income Effects

When the price of a good goes up, the budget line shifts left, showing lower utility. If the price drops, the budget line shifts right, showing higher utility. The extent of these changes depends on individual preferences.

- Substitution Effect: When a good gets pricier, people buy less of it and more of a cheaper alternative. If oranges cost more, people buy more apples. If oranges cost less, they buy more oranges.

- Income Effect: A price increase reduces buying power, while a price decrease increases it. If oranges become more expensive, you can afford fewer oranges with the same income. If they become cheaper, you can afford more.

Figure 7.6 Substitution and Income Effects

In Figure 7.6, Ogden chooses between haircuts and personal pizzas:

- Original Budget: $120, haircuts at $20, and pizzas at $6.

- Original Choice (Point A): 10 pizzas and 3 haircuts.

When the price of haircuts rises to $30:

- New Budget Line: Rotates inward.

- New Choice (Point B): 10 pizzas and 2 haircuts.

- Substitution Effect (A to C): Ogden buys fewer haircuts and more pizza.

- Income Effect (C to B): Reduced buying power, leading to fewer haircuts.

Interpretation:

The substitution effect makes people buy less of the more expensive goods and more of the cheaper ones. The income effect reduces overall consumption if both goods are normal. Ogden buys the same amount of pizza but fewer haircuts after the price hike.

Both effects always occur together, influencing consumer choices simultaneously.

Driving the Demand Curve

When the price of a good changes, the budget constraint rotates, leading to changes in the quantity demanded as individuals seek their highest utility. This is the foundation of demand curves, which show the relationship between prices and quantity demanded.

In Figure 7.7 (a):

- Housing vs. Everything Else: The budget constraint represents choices between housing and other goods.

- Original Budget: At the original price Po, the preferred choice is Mo, with a quantity of housing Qo.

- Increasing Prices: As housing prices rise to P1, P2, and P3, the budget constraint rotates inward, leading to new utility-maximizing choices M1, M2, and M3 with decreasing quantities of housing Q1, Q2, Q3.

In Figure 7.7 (b):

- Demand Curve: This graph shows the demand curve for housing, illustrating the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded.

- Points on Demand Curve: The points E0, E1, E2 and 3 correspond to prices, P0, P1, P2 and 3 and quantities Q0, Q1, Q2 and Q3 from Figure 7.7 (a).

Figure 7.7 Driving a Demand Curve

The demand curve reflects the choices people make to maximize utility given their budget constraints. While economists can’t measure utility directly, they can observe the price and quantity demanded to understand consumer behavior.

Applications of Budget Constraint Framework in Government and Business

The utility-maximizing budget constraint framework provides a comprehensive tool for understanding consumer behavior. By examining how individuals adjust their consumption in response to changes in prices and income, policymakers and businesses can better anticipate the effects of their decisions. Here are three real-world examples with detailed data:

Case Study 1: Sugar Tax in Mexico

In 2014, Mexico introduced a 10% tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) to address rising obesity rates. This tax led to an average reduction of 7.6% in the purchase of sugary drinks in the first year, with low-income households showing the largest decrease at 11.7% (PLOS) (Cambridge). The tax aimed to decrease the consumption of high-calorie beverages and promote healthier alternatives like water and unsweetened drinks.

However, the impact extended beyond just beverage choices. Households reallocated their budgets, reducing spending on other discretionary items such as snacks and dining out. The policy also demonstrated potential long-term health benefits, projecting a reduction in obesity prevalence by up to 2.5% among the population (PLOS) (Cambridge).

Case Study 2: Fuel Price Hike in France

In 2018, the French government increased fuel taxes to encourage environmentally sustainable practices. This tax hike led to a significant behavioral shift among consumers. Many people reduced their car usage, opting for public transportation, cycling, or carpooling instead. The demand for fuel dropped by approximately 4%, illustrating a relatively elastic response to the price increase.

Additionally, households adjusted their spending in other areas to manage the higher fuel costs. Non-essential expenditures, such as entertainment and dining out, saw noticeable reductions. This change not only affected individual consumption patterns but also had a ripple effect on sectors dependent on discretionary spending, underscoring the interconnectedness of economic behaviors.

The increased fuel prices also spurred interest in more fuel-efficient vehicles and alternative energy sources. Sales of electric and hybrid cars saw an uptick as consumers looked for ways to mitigate the impact of higher fuel costs. This shift supported the government’s goal of reducing carbon emissions and promoting sustainable transportation options.

However, the policy also faced significant public backlash, leading to widespread protests and the rise of the “Yellow Vests” movement. This reaction highlighted the challenges of implementing environmental policies that affect household budgets, especially for lower-income families who spend a larger share of their income on transportation.

Case Study 3: Tobacco Tax in Australia

In 2010, the Australian government increased the excise tax on tobacco as part of a public health strategy to reduce smoking rates. The price of cigarettes rose by 25%, which led to a noticeable drop in tobacco consumption. Research showed that smoking prevalence declined by approximately 3.2 percentage points within the first year of the tax hike.

The higher cost of cigarettes prompted many smokers to either quit or reduce their consumption. Additionally, the demand for smoking cessation products, such as nicotine patches and gum, increased as individuals sought alternatives to manage their addiction. This shift illustrates the effectiveness of tax policies in influencing health-related behaviors through economic incentives.

Households also reallocated their spending in response to the higher tobacco prices. Money previously spent on cigarettes was diverted to other areas, including groceries, healthcare, and leisure activities. This reallocation had positive effects on overall household welfare and disposable income.

The tobacco tax also generated significant revenue for the government, which was then reinvested into public health programs and campaigns aimed at further reducing smoking rates. This approach demonstrated a successful use of fiscal policy to achieve dual objectives: improving public health and increasing government revenue.

However, the policy faced criticism from some quarters. Opponents argued that the tax disproportionately affected lower-income individuals, who are more likely to smoke and thus spend a larger portion of their income on cigarettes. This concern highlighted the need for complementary measures, such as targeted support for smoking cessation programs, to reduce the regressive impact of the tax.

The Unifying Power of the Utility-Maximizing Budget Set Framework

These case studies underscore the versatility and predictive power of the utility-maximizing budget constraint framework in explaining consumer behavior. Here’s how this framework is applied and why it’s so insightful:

Understanding Consumer Reactions

- Utility Maximization: Consumers aim to achieve the highest level of satisfaction (utility) given their budget constraints. When faced with changes in prices or income, they adjust their consumption to maintain or maximize their utility.

- Behavioral Adjustments: The sugar tax in Mexico and the fuel tax in France show how consumers reallocate their budgets in response to price changes. In Mexico, the tax on sugary drinks prompted consumers to switch to healthier beverages, while in France, higher fuel prices led to increased use of public transportation and reduced spending on non-essential items.

Policy Implications

These adjustments have significant policy implications. For instance, the success of Mexico’s sugar tax in reducing sugary drink consumption can inform similar public health interventions in other countries. Similarly, the fuel tax in France highlights the potential for using price mechanisms to promote environmental sustainability.

Broader Economic Impacts

- Spillover Effects: Changes in the price of one good can affect the consumption of other goods. In Mexico, reduced spending on sugary drinks also led to a decrease in spending on snacks and dining out. In France, the higher fuel prices affected spending on entertainment and other non-essential items.

- Elasticity of Demand: The degree to which consumers change their behavior in response to price changes (price elasticity of demand) varies. The inelastic demand for home heating in the US, compared to the relatively elastic response to sugary drink prices in Mexico, illustrates how different goods and services have different elasticity characteristics.

- Long-term Benefits: Beyond immediate consumption changes, these policies can lead to long-term benefits. The projected decrease in obesity rates in Mexico and potential reductions in carbon emissions in France demonstrate the broader societal advantages of such interventions.

In summary, the framework not only explains individual consumer choices but also provides valuable insights into the broader economic and societal impacts of price changes and policy interventions.

Who Should Control the Household Income to Maximize Utility?

Different research studies highlight that who controls household income can indeed make a significant difference in spending patterns and overall utility. Whether through policy changes, microfinance initiatives, or cash transfer programs, empowering women or structuring financial responsibilities collaboratively within households can lead to more efficient allocation of resources, improved family welfare, and enhanced long-term outcomes for children and family members alike. Understanding these dynamics can inform policies and practices aimed at maximizing household utility and promoting economic well-being globally.

World Around Us: Who Should Control the Household Income to Maximize Utility?

Case Study 1: Microfinance Initiatives in Bangladesh

- In Bangladesh, microfinance programs often target women as recipients of loans and financial resources.

- Research by the World Bank indicates that women who participate in these programs tend to allocate more resources towards children’s education and health compared to men.

- Impact: Children in households where women control finances show improved nutrition and educational outcomes, contributing to long-term family welfare.

Case Study 2: Dual-Income Families in the United States

- Dual-income households in the US often divide financial responsibilities based on expertise and availability.

- According to research by the Pew Research Center, in 2019, 63% of dual-income couples reported sharing financial decision-making equally.

- They maintain joint accounts for household expenses while each partner has a separate account for personal spending.

- Impact: This setup allows them to manage shared financial goals effectively while maintaining individual autonomy, leading to reduced financial stress and enhanced satisfaction.

Case Study 3: Cash Transfer Programs in Brazil

- Brazil’s Bolsa Família program provides cash transfers to low-income families, often distributed to mothers.

- Studies by the Inter-American Development Bank show that when mothers receive these transfers, spending patterns prioritize children’s education, healthcare, and nutrition.

- Approach: With control over household income, a lady invests in her children’s education, buys nutritious food, and ensures access to healthcare services.

- Impact: Children in households where mothers control income through Bolsa Família exhibit better school attendance, improved health outcomes, and reduced poverty levels over time.

Behavioral Economics: An Alternative Framework for Consumer Choice

Behavioral economics is a field that merges insights from psychology with economic theory to understand how real people make decisions. Traditional economics assumes that people are perfectly rational agents who make decisions by carefully weighing all available information to maximize their utility. However, behavioral economics challenges this notion by demonstrating that human behavior often deviates from these rational standards due to various psychological factors.

Key Concepts in Behavioral Economics

Loss Aversion

Definition: People tend to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. This means the pain of losing $10 is often greater than the pleasure of gaining $10.

Example: Investors may hold onto losing stocks longer than rational analysis would suggest because the pain of realizing a loss is too great.

Present Bias

Definition: People tend to give stronger preference to immediate rewards over future ones, often leading to uncertainty and inconsistent decision-making over time.

Example: Many people fail to save for retirement because the benefits of saving are in the distant future, whereas the benefits of spending are immediate.

Hyperbolic Discounting

Definition: This describes the tendency for people to choose smaller, immediate rewards over larger, later rewards disproportionately more as the delay occurs sooner rather than later.

Example: Someone might choose to receive $50 today over $100 in a year but might prefer $100 in six years over $50 in five years.

Mental Accounting

Definition: People treat money differently depending on its source or intended use, even though money is convertible.

Example: A person might enjoy a $100 gift but be very careful with $100 earned from work.

Anchoring

Definition: People rely heavily on the first piece of information (the “anchor”) when making decisions.

Example: If you see a shirt marked down from $100 to $50, you might think it’s a good deal, even if $50 is more than you would normally pay.

Framing Effects

Definition: People react differently to the same information depending on how it is presented.

Example: More people will choose surgery if told it has a 90% survival rate than if told it has a 10% mortality rate.

Nudges (Boosts)

Definition: Small design changes in the environment that can significantly alter behavior without restricting choices.

Example: Automatically enrolling employees in retirement savings plans, with the option to opt-out, greatly increases participation rates.

World Around Us: Behavioral Economics

Case Study 1: Loss Aversion in Stock Markets

Example: Investors are more likely to sell stocks that have gained in value rather than those that have lost value, even if the latter has less potential for future growth.

The pain of realizing a loss is more impactful than the pleasure of a gain, leading to suboptimal investment decisions.

Impact: This behavior can lead to poor portfolio performance.

Case Study 2: Present Bias in Saving for Retirement

Despite knowing the importance of saving for retirement, many people delay enrolling in retirement plans or save insufficiently.

Reason: Immediate consumption is more appealing than the abstract future benefit of having a retirement fund.

Impact: This can result in inadequate savings for retirement, leading to financial difficulties in old age.

Case Study 3: Mental Accounting with Tax Refunds

People often spend tax refunds on luxuries rather than paying down high-interest debt.

Reason: Tax refunds are seen as “bonus” money, leading to different spending behavior compared to regular income.

Impact: This can lead to higher long-term debt and financial stress.

Behavioral Economics: Boosting Individual’s Wellbeing

Behavioral economics studies how psychological, social, and emotional factors affect economic decisions. One key insight is that spending on family; recreation, holidays, and dining out can significantly enhance individual well-being and productivity. Recognizing this, major multinationals offer bonuses and long weekends to boost employee satisfaction and productivity. This approach underscores the importance of work-life balance and its impact on organizational success.

Deviation from Traditional Economics:

Behavioral Behavioral economics explores how human behavior deviates from traditional economic theories, which assume rational decision-making. It examines how factors like emotions, social influences, and emotional biases impact economic choices.

Utility of Spending on Well-Being:

Investing in activities that enhance personal well-being—such as family time, recreation, holidays, and dining out—can lead to increased happiness and productivity. These activities allow individuals to recharge, leading to better performance at work.

World Around Us: Boosting Individual’s Wellbeing

Case Study 1: Google’s Comprehensive Employee Benefits

Family and Recreation: Google provides a range of on-site amenities, including gyms, massage services, and recreational facilities. These benefits allow employees to balance work and personal life, leading to higher job satisfaction and productivity.

Holidays and Dining Out: Google offers generous vacation policies and free restaurant meals. Employees are encouraged to take time off and enjoy quality dining experiences, which enhances their overall well-being.

Increased Productivity: The well-being of employees translates into higher productivity and creativity.

Low Turnover: Google maintains a low employee turnover rate and consistently ranks as a top employer.

Employee Satisfaction: Google ranked 6th on Glassdoor’s Best Places to Work list in 2020.

Financial Performance: Alphabet, Google’s parent company, reported revenue of $182.5 billion in 2020, reflecting productivity gains from a satisfied workforce.

Case Study 2: Salesforce’s Ohana Culture

Family and Recreation: Salesforce supports employees with parental leave, adoption assistance, and various family support programs, fostering a strong sense of community.

Holidays and Dining Out: Salesforce provides ample paid time off and organizes team-building events and family-friendly outings. These activities enhance employees’ work-life balance and job satisfaction.

Enhanced Team Spirit: The Ohana culture promotes teamwork and high productivity.

Employee Loyalty: High levels of employee loyalty and satisfaction contribute to Salesforce’s success.

Employee Retention: Salesforce has a low voluntary turnover rate of about 7%.

Revenue Growth: Salesforce’s revenue reached $21.25 billion in 2021.

Case Study 3: Netflix’s Unlimited Vacation Policy

Family and Recreation: Netflix’s unlimited vacation policy encourages employees to take as much time off as they need to maintain a healthy work-life balance.

Holidays and Dining Out: Netflix provides travel and meal stipends to support employees’ leisure activities, ensuring they can enjoy quality time outside of work.

Boosted Creativity: Freedom to take time off leads to higher creativity and innovation.

Job Satisfaction: Employees report high job satisfaction and engagement.

Employee Feedback: Netflix employees highlight the unlimited vacation policy as a major benefit in surveys.

Business Success: Netflix’s innovative culture has driven its growth, with revenue reaching $25 billion in 2020.

Summary

Behavioral economics provides valuable insights into how spending on personal well-being can enhance productivity. By offering bonuses, long weekends, and various employee benefits, companies like Google, Sales-force, and Netflix have demonstrated that investing in employee satisfaction leads to greater productivity, creativity, and overall business success. These case studies highlight the importance of fostering a work environment that supports personal well-being, ultimately benefiting both employees and employers.

Intertemporal Choices

Intertemporal choices are decisions where the results affect different points in time. This means considering what happens now versus what happens later. These choices often show two key behaviors:

- Present Bias: People tend to favor things that bring immediate satisfaction over things that might benefit them more in the future. For instance, spending money on something enjoyable today rather than saving it for future needs like education or retirement.

- Hyperbolic Discounting: This refers to the tendency for people to prefer smaller rewards sooner rather than larger rewards later, even if waiting would bring greater benefits. For example, choosing to receive a small amount of money immediately rather than waiting a bit longer for a larger amount.

Example: Spending Money Now or Saving for the Future

Imagine you have $100. You can either spend it all on something fun today, like going to a theme park or save some or all of it for later. Here’s how this decision involves both present bias and hyperbolic discounting:

- Present Bias: You might feel more tempted to use the money now because the enjoyment of going to the theme park is immediate. The idea of saving for something in the future, like a bigger trip or buying something important, might not feel as rewarding right now.

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Even if you know saving part of the money could lead to a bigger, more rewarding experience later, the immediate gratification of spending it now could seem more attractive. Waiting for a larger reward can feel less appealing compared to the instant joy of spending money today.

Importance of Balancing Intertemporal Choices

Understanding these behaviors helps in making better decisions for your future. It’s about finding a balance between enjoying things now and planning for what you’ll need later. By thinking ahead and considering the long-term benefits, you can make choices that lead to greater satisfaction and security over time.

Interpreting an Intertemporal Budget Constraint

An intertemporal budget constraint showcases the trade-off between current and future consumption, emphasizing the importance of balancing spending across different time periods. Balancing this trade-off is crucial for financial health.

Example: If you have $1,000 today and can either spend it all now or save some for the future, an intertemporal budget constraint helps visualize the impact of these choices on future financial stability.

World Around Us: Intertemporal Budget Constraints

Case Study 1: U.S. Retirement Savings Crisis

- Many Americans face challenges in balancing current spending with future financial security, particularly regarding retirement savings.

- Current Situation: A significant portion of Americans struggle with saving for retirement. According to the National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS), as of 2021, 45% of working-age households have no retirement savings at all.

- Future Consequence: This lack of savings indicates a potential future financial crisis for retirees. The NIRS reports that the median retirement account balance for all working-age households is only $3,000 and $12,000 for near-retirement households.

- Trade-Off: The intertemporal budget constraint is evident as individuals prioritize current consumption over future savings. Financial advisors often recommend saving at least 15% of one’s income for retirement to ensure adequate funds for future consumption.

- Implications: This case highlights the need for better financial education and planning tools to help individuals balance their current spending with the necessity of saving for future needs.

Case Study 2: Japan’s Aging Population and National Savings

- Japan faces a unique challenge with an aging population, impacting the nation’s savings rates and consumption patterns.

- Current Situation: Japan has one of the highest life expectancies globally and a rapidly aging population. As of 2021, 28.7% of Japan’s population was aged 65 or older.

- Future Consequence: This demographic shift pressures the country’s pension system and increases the need for elderly care. The government and individuals must save more to support longer retirement periods.

- Trade-Off: Japanese households tend to save more of their income compared to other countries. According to the OECD, Japan’s household savings rate was approximately 11% in 2020, significantly higher than the U.S. savings rate of around 7.6%.

- Implications: The high savings rate in Japan reflects an understanding of the intertemporal budget constraint, where current savings are prioritized to ensure future financial stability and healthcare needs.

Case Study 3: Education Loans and Future Earnings in the United States

- Context: Many American students take out loans to finance their education, impacting their future financial health.

- Current Situation: Student loan debt in the United States reached $1.7 trillion in 2021, with the average debt per borrower around $30,000.

- Future Consequence: The burden of student loans affects future consumption and savings. Graduates often delay purchasing homes, saving for retirement, and other significant expenditures.

- Trade-Off: Students face an intertemporal budget constraint where they must balance the immediate need for education funding with the long-term impact of loan repayment. The trade-off involves investing in education now with the expectation of higher future earnings. However, not all graduates see a return on investment that justifies the debt, leading to financial strain.

- Implications: This case underscores the importance of considering the future implications of current financial decisions, especially regarding education funding. It also highlights the need for policies that address the rising cost of education and the burden of student debt.

Summary

These case studies illustrate the practical application of intertemporal budget constraints in various contexts, from retirement savings and national economic policies to education financing. Each example shows how balancing current consumption with future financial needs is essential for long-term financial health and stability. Understanding these trade-offs helps individuals and policymakers make informed decisions that align with their financial goals.

Behavioral economics enriches our understanding of economic decision-making by integrating psychological insights. It explains why people often make seemingly irrational choices, highlighting the complexity of human behavior. Recognizing these patterns can lead to better policies and tools to help individuals make more rational and beneficial decisions.

Increase Earnings with Higher Education

Understanding how higher education enhances earning potential is crucial for students making decisions about their educational and career paths. By acquiring specialized skills, accessing career advancement opportunities, and leveraging credentials and networks, individuals can position themselves for higher-paying jobs and greater long-term financial stability. Higher education not only prepares individuals for specific careers but also equips them with the tools to adapt and thrive in evolving job markets.

Skills and Knowledge Acquisition:

Higher education provides specialized skills and knowledge that are valued by employers. For example, a degree in engineering equips graduates with technical expertise, while a degree in business administration teaches management and analytical skills.

Impact: Employers are willing to pay higher salaries for individuals who possess these specific skills and knowledge, which are often required for roles with greater responsibility and complexity.

Career Advancement Opportunities:

Higher education opens doors to career advancement opportunities that may not be accessible to those with lower educational qualifications. Many professions have educational requirements for promotion to higher levels.

Example: A nurse with a bachelor’s degree may be eligible for supervisory or administrative roles that offer higher salaries compared to entry-level positions that require only a diploma.

Higher Demand for Specialized Roles:

Industries such as technology, healthcare, finance, and engineering have a high demand for employees with specialized knowledge and qualifications.

Impact: Graduates with relevant degrees often command higher salaries due to their ability to fill critical roles that require advanced expertise.

Credentialing Effect:

Having higher education credentials signals to employers that an individual has dedication, perseverance, and the ability to learn complex subjects.

Example: Employers often prefer candidates with degrees for positions that involve problem-solving, critical thinking, and decision-making.

Networking and Opportunities:

Higher education provides opportunities for networking with peers, professors, and professionals in the field through internships, industry events, and alumni networks.

Impact: Networking can lead to job referrals, mentorship opportunities, and access to job openings that are not advertised publicly, potentially leading to higher-paying positions.

Global Marketability:

In an increasingly globalized economy, employers value candidates with international perspectives and educational backgrounds from reputable institutions.

Example: Graduates from top universities often have better opportunities for global career placements and higher salaries compared to those from less recognized institutions.

World Around Us: Increased Earnings with Higher Education

Case Study 1: United States

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, individuals with a bachelor’s degree had median weekly earnings of $1,305 in 2020, compared to $781 for those with only a high school diploma.

Over a lifetime, college graduates earn significantly more than individuals with lower levels of education.

Case Study 2: India

Research from the National Sample Survey Office in India indicates that professionals with higher education qualifications, such as engineering or medicine, earn significantly higher salaries than those with lower educational attainment.

Industries, such as information technology and engineering, offer lucrative opportunities for graduates with technical skills.

Case Study 3: South Korea

Studies from the Korean Educational Development Institute highlight that college graduates in South Korea earn significantly higher salaries on average compared to high school graduates.

Higher education is viewed as essential for career advancement in industries such as finance, technology, and manufacturing.

Elaboration of Substitution and Income Effects with Indifference Curve

Indifference curves are a powerful analytical tool in economics, providing insight into consumer choices without requiring numerical values for utility. They help us understand how consumers make utility-maximizing decisions and how their choices respond to changes in prices, wages, or rates of return. This process is broken down into the substitution and income effects, which can be visualized using diagrams.

Steps to Sketch Substitution and Income Effects

Step 1: Initial Budget Constraint

Begin with a budget constraint showing the choice between two goods, which we will call “candy” and “movies.” Choose a point A, representing the optimal choice where the indifference curve is tangent. At this stage, it is often easier not to draw the indifference curve yet.

- X-axis: Candy

- Y-axis: Movies

- Initial Budget Line: A downward-sloping line representing the initial budget constraint.

- Point A: Optimal choice on the initial budget line.

Step 2: Change in Price

Now suppose the price of movies rises. This shifts the budget set inward, representing a higher price for movies and pushing the decision-maker to a lower level of utility. Draw only the new budget set at this stage.

- New Budget Line: A steeper downward-sloping line that intersects the original line at the x-axis.

- Intersection Point: Lower on the y-axis compared to the original budget line.

Step 3: Insert a Dashed Line for Substitution Effect

To distinguish between substitution and income effects, insert a dashed line parallel to the new budget line. This dashed line helps to separate the two effects:

- Substitution Effect: The change in consumption due to the price shift, with utility unchanged.

- Income Effect: The change in consumption due to the shift to a new indifference curve, with relative prices unchanged.

- Dashed Line: Parallel to the new budget line and close to point A.

Step 4: Draw the Original Indifference Curve

Draw the original indifference curve, tangent to both point A on the initial budget line and point C on the dashed line. The substitution effect is the movement along the original indifference curve from A to C, showing the change in consumption as prices change but utility remains constant.

- Indifference Curve: Tangent at points A and C.

- Substitution Effect Arrows: “s” on the vertical axis (down) and “s” on the horizontal axis (right).

Step 5: Choose Utility-Maximizing Point B

Identify the new utility-maximizing point B on the new budget line. This point reflects whether the substitution or income effect has a larger impact on the good (candy) on the horizontal axis. The income effect is the movement from C to B, showing how choices shift due to the decline in buying power and movement between two levels of utility.

- Point B: On the new budget line.

- Income Effect Arrows: “i” on the vertical axis (down) and “i” on the horizontal axis (left).

Variations for Practice

To deepen your understanding of substitution and income effects, practice with the following variations:

- Price Falls: Instead of a price rise, consider how a price fall affects the goods.

- Different Goods: Analyze how a price change affects goods on either the vertical or horizontal axis.

- Relative Effects: Sketch diagrams where the substitution effect exceeds the income effect, the income effect exceeds the substitution effect, and the two effects are equal.

Alternative Method

The dashed line can also be drawn tangent to the new indifference curve and parallel to the original budget line. This method may be more insightful for some, but it yields the same results regarding the direction and relative sizes of the substitution and income effects.

By following these steps and practicing various scenarios, students can effectively visualize and understand the substitution and income effects, enhancing their grasp of consumer behavior in response to price changes.

Today we end up understanding the theory of consumption. It provides a framework for indulging how consumers allocate their resources to maximize utility. It integrates concepts of utility, budget constraints, and the effects of price and income changes, offering insights into consumer behavior and the impact of economic policies.

References:

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- National Bureau of Economic Research (2010). Household Consumption During the 2008 Recession.

Research Suggestions for Economists

- Behavioral Responses to Economic Stimuli: Investigate how different consumer groups adjust their consumption patterns in response to economic stimuli like tax cuts, rebates, or subsidies.

- Impact of Behavioral Nudges on Saving Habits: Study the long-term effects of behavioral nudges, such as automatic enrollment in savings programs, on household financial stability.

- Mental Accounting and Financial Decision-Making: Explore the role of mental accounting in how consumers allocate resources during times of economic scarcity and its impact on long-term financial health.

- Consumer Behavior during Recessions: Analyze the persistence of luxury consumption during recessions and the psychological factors that drive consumers to maintain such spending.

- Anchoring Effects on Price Sensitivity: Research how anchoring to past prices influences consumer sensitivity to price changes in essential and non-essential goods during economic downturns.

Critical Thinking Questions

- How do cultural differences influence consumer choices in different countries?

- How do changes in consumer preferences affect the shape and position of indifference curves? Can you think of some real-life examples where a shift in preferences led to significant changes in consumer behavior?

- What role does advertising play in irrational consumer behavior?

- How does a substantial increase or decrease in income influence a household’s consumption choices? Can you relate this to any historical events or economic policies?

- How do government subsidies affect the demand for agricultural products?

- Why might consumers prefer branded products over generic ones?

- How do substitution and income effects explain the consumption choices of individuals when the price of a necessity like gasoline increases? Are there any real-world examples where these effects have been particularly evident?

- How might changes in interest rates influence a consumer’s decision to save or spend? What are some real-world scenarios where changes in interest rates have had a noticeable impact on consumer behavior?

- How do different wage rates affect the labor-leisure choices of individuals? Can you provide examples of how changes in minimum wage laws have influenced labor supply?

- How do psychological factors such as rational biases or heuristics influence consumer decisions that deviate from traditional utility-maximizing behavior? Can you identify any marketing strategies that take advantage of these biases?

- How do changes in income affect the consumption of luxury goods versus necessities?

- What are the implications of diminishing marginal utility for consumer spending?

- How can businesses use cross-price elasticity to their advantage?

- In what ways can public policies shift consumer preferences?

- How do intertemporal choices impact personal financial planning?

- What strategies can governments use to influence consumer saving behavior?

- How might government policies such as taxation or subsidies alter the budget constraints of households? What are some examples of how such policies have successfully or unsuccessfully influenced consumption patterns?

- How do cultural norms and social influences shape consumer preferences and choices? Can you think of any instances where social movements or trends have significantly altered consumption habits?

- How can the theory of consumption be applied to encourage more sustainable consumer behavior? Are there any examples of policies or initiatives that have successfully promoted environmentally friendly consumption?

- How do technological advancements influence consumer preferences and the budget constraint? Can you provide examples of how new technologies have disrupted traditional consumption patterns?

- How do changes in the price of one good affect the demand for its complementary and substitute goods? Provide a scenario where the price of coffee increases and analyze the impact on the demand for tea and sugar.

- Explain how indifference curves can be used to represent consumer preferences and the trade-offs they are willing to make. Sketch indifference curves for a consumer choosing between leisure and work hours.

- If the price of a normal good decreases how do the income and substitution effects explain the change in quantity demanded? Use a numerical example where the price of good X falls from $10 to $5, and the consumer’s income remains $100.

- How do consumers adjust their choices when faced with a change in budget constraints due to an increase in taxes? Illustrate this with a simple numerical example where a consumer’s income decreases from $1,000 to $900 due to taxation.

- How does the price elasticity of demand influence a firm’s pricing strategy? Calculate the price elasticity of demand if the quantity demanded for a product decreases from 50 units to 40 units when the price increases from $10 to $12.

- How does advertising influence consumer preferences and the demand curve for a product? Analyze the impact of a $1 million advertising campaign that increases the quantity demanded from 1,000 units to 1,500 units at a constant price of $10 per unit.

- Can you explain how globalization has transformed your everyday consumption choices with social media access to the worldview?