Global population growth is a testament to human progress, with an eight-fold increase in the number of humans alive since 1800. In 2015, the global GDP was 90 times more than in 1820. Caused by advancements in international healthiness, wealth and tranquillity, people today live elongate, securer and more nutritious lives than at any moment in history. Despite advances in social norms in health, education and technology, welfare has yet not been established equity with regional and global challenges to equilibrium, inhibiting human prospects globally. Investment in women’s entrepreneurship and their participation in the economy, higher labour standards, improvements in research & development, policy to reach sustainable development growth, and understanding & handling of the crises can lead to income equality for the globe. Research has demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated current inequalities. The World Inequality Report, produced by the World Inequality Lab, found that assets and revenue inequality stay enunciated worldwide.

The COVID predicament has worsened inequalities between the rich and the remainder of the inhabitants of the globe. However, in wealthy nations, government intervention discouraged a tremendous climb in deprivation. This was not the case in poor nations. This demonstrates the significance of social circumstances in the combat against poverty.

The research emphasises the importance of global gain and asset inequalities. At a global level, the average income for an adult is $23,380 when accommodated for Purchasing Power Parity or PPP. However, the research explains that this obscures broad disparities between and within nations. The richest 10% of the global inhabitants presently occupy 52% of the global wealth. The poorest half of the global population gains just 8% of this global wealth.

On average, an individual from the top 10% will earn $122,100, but an individual from the bottom half will earn just $3,920. And, when it donates to capital (valuable assets and commodities over and above income), the gap is consistently widening. The most inferior half of the global population possesses just 2% of the global wealth, while the richest 10% own 76% of all wealth. But, the research also informs that significant inequality can operate within nations. National average income statuses are insufficient predictors of inequality. Higher-income nations can be unequal, as can low- and middle-income countries.

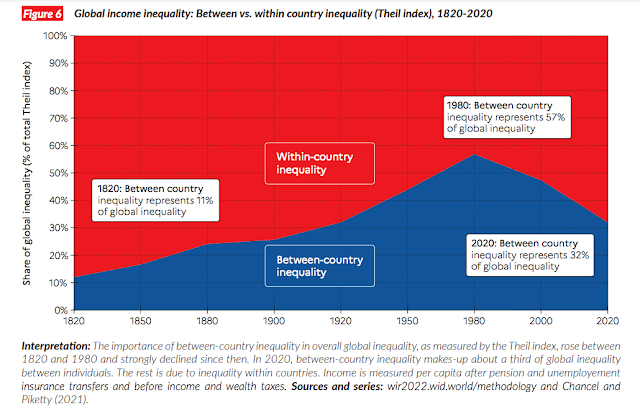

Indeed, while for the last two decades, global inequalities between nations have decreased, income inequality has increased within most nations. The average income gap between the top 10% and bottom 50% of individuals within countries has almost duplicated across that span.

2020 observed the steepest growth in the wealth of the global rich personals and their share of assets increased rapidly. Indeed, since 1995, the share of global wealth possessed by the richest has increased from 1% to over 3%. The chart below illustrates the world’s richest have grabbed a disproportionate percentage of global wealth over current decades.

Handling the challenges of the 21st Century will not be achievable without substantial reallocation of assets & earnings inequality. The research analyses many alternatives primarily embedded in tax approach, to tackle income & wealth inequality. The models suggest frameworks from across the globe and throughout contemporary history and conclude that inequality is always a political intention and understanding from approaches enforced in other nations or at some other points in the period is necessary to develop more equitable growth tracks.

The gap between rich and poor is getting higher in the globe’s richest nations and specifically America as top earners’ incomes glide; while others stagnate. In a study of its member countries, the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development stated that rich and poor households are not only facing the widening income gap; but in nations such as America, Canada and Germany, the rich are far far away from the middle-income earners. The countries are potentially facing alarming influences. If the global economic crisis flashes along recession the threats will boost over time.

Inequality endangers social mobility, especially in America children accomplishing more profitable goals than their parents, and the poor improving their future through hard work, which is inferior in America than in nations such as Denmark, Sweden and Australia.

The data of about two decades in the investigation (1985-2005) witnessed the expansion of global commerce and the internet and a period of widespread substantial economic growth. Most countries studied are developed nations, particularly in Europe.

America has the highest inequality and poverty in the OECD after Mexico and Turkey, and the gap has boosted rapidly since 2000. France has seen inequalities decline in the past 20 years as poorer labours are more paid. The study was useful for policymakers because it is reaching out just as the globe is experiencing the worst crisis in decades.

With several OECD countries already in recession, the important question arises in our minds whether governments can control a potential decrease in higher earners’ incomes from flashing a second surge drilled to the lowest-income households. The growing inequality gap overlapped with a duration of substantial economic growth. If a rising surge didn’t boost all growth variables then how will they be influenced by a diminishing surge?

With countries all over the world, promoting trillions of dollars in return, providing finance to shore up banks, if they can allocate budgets to save banks, governments can finance a sufficient unemployment insurance scheme and employment subsidies. Countries need to function to sustain employment as a reaction to broadening inequality and stuttering economies. They should accomplish more to familiarise the whole workforce and not only the rich while enabling individuals to obtain employment opportunities and growing incomes for the labour class instead of depending on sociable advantages. Higher-income inequality suppresses upward growth between generations, pushing it challenging for capable, talented and hardworking individuals to gain the compensations they deserve. It has polarized communities, split territories within countries and engraved the world between rich and poor. In America, the wealthiest 10 per cent make an average of $93,000, the highest level in the OECD. The poorest 10 per cent earn an average of $5,800 – about 20 per cent lower than the OECD average. Social growth is lowest in countries with high inequality, such as America, England, and Italy.

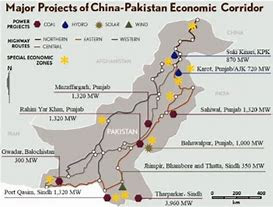

Now we continue over findings for Pakistan. There is very less literature review available particularly for Pakistan. So we are quoting the conclusion of recent research on Income inequality in Pakistan. The study develops the current income inequality in Pakistan by analysing the main causalities of inequality and its transformations over a decade (2005–2006 to 2015–2016). The study analyses the major factors such as age, gender, education, profession and job grade as drivers of income inequality. It says, “Although age and gender are the most notable classifications defining the status of income inequality for Punjab and Sindh; however, no substantial shifts were observed in their relative contribution to balance income inequality over the decade. For KP, the relative contribution of gender has reduced by more than 50% from 23.2 to 10.2% whereas the relative inequality for age has increased from 26.8 to 40.1% over the decade. Conversely, gender’s relative share in income inequality in Balochistan has increased drastically from 11.6 to 49.3%. A tremendous advancement in higher education in Pakistan was witnessed during the study period due to the restructuring of the higher education governing body (HEC) in 2002. On balance, increased or professional and skilled education has recreated a substantial role in removing the income inequality across all four provinces, particularly in KP and Balochistan, with a change in relative inequality from 10.8 and 10.1 to 25.8 and 44.8, respectively. On symmetry, any level of education is lowering income inequality in Sindh, KP and Balochistan and only professional education in Punjab. In terms of occupation, legislators and senior professionals occupations are reducing income inequality in all provinces except for Sindh, professionals, managers, technicians and associate professionals for Punjab and Balochistan, and plant and machine operators and assemblers in Sindh, KP and Balochistan. Employer or self-employed job status decreases the income inequality in Punjab and Balochistan and cultivators, sharecropper, and livestock in Punjab and Sindh. Approaches employed to improve the accessibility of primary education to the masses and proliferation in disciplines such as agriculture and fishery sector need to be continued to lower inequality further. Women in Pakistan should be facilitated to partake in the labour force to remove the inequality in income due to gender. Facilities should be furnished to agricultural and fishery workers in Balochistan so that they can contribute to the value addition of their products inside the province. This will enhance the employability of the locals and help in reducing income inequality”.

(Pictures credit: to the links shared in the article).